Cosimo Matassa

Italian American businessman, studio owner, and recording engineer Cosimo Matassa was one of the seminal figures of popular recorded music.

THE COSIMO MATASSA FAMILY

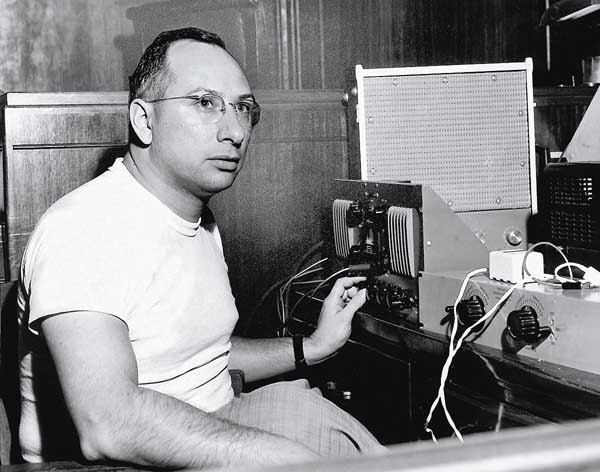

Cosimo Matassa in his studio.

Italian American businessman, studio owner, and recording engineer Cosimo Matassa was one of the seminal figures of popular recorded music. Virtually every New Orleans rhythm-and-blues (R&B) record that made the charts between the late-1940s and the early-1970s was recorded at one of his four studios. Matassa’s engineering talent and ear for a good tune led to an amazing string of national hits spanning those decades. Matassa was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame during its 27th annual ceremony at the historic Public House in Cleveland, Ohio on April 14, 2012.

Cosimo (usually pronounced “Cosmo”) Matassa was born in New Orleans on April 13, 1926. His father John emigrated from Sicily in 1910; in 1924, John Matassa opened a small grocery store, Matassa’s Market, at the corner of Dauphine and St. Philip streets in New Orleans’ French Quarter. Though Cosimo Matassa had grown up working in his father’s store, he demonstrated talents outside the grocery business. As a student at McDonogh 15 Elementary School (715 St. Philip Street), he won a spelling bee and its prize: a trip to the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair.

After graduating from Warren Easton High School (3019 Canal Street), Matassa studied chemistry for roughly two years at Tulane University but dropped out because, as he puts it, “When I finally realized what a chemist was, I decided not to be one.” Since he was ineligible to be drafted into the military for physical reasons, his father gave him a choice: go back to school or start working.

J&M Recording Service

Besides his grocery business, John Matassa and his partner Joe Mancuso ran J&M Amusement Services, placing jukeboxes in bars and restaurants on commission. Cosimo began selling used records from the jukeboxes, and soon customers started asking about new releases as well. Noticing the demand for records and the lack of places to buy them in New Orleans, he and Mancuso opened the J&M Music Shop at 838 North Rampart Street, on the corner of Rampart and Dumaine Streets. The records quickly outperformed other parts of the J&M enterprise. Matassa also noted a dearth of places in the city to make records, so he installed recording equipment in the back of the store in 1946, at first making amateur recordings of personal messages, band demos, high school glee club performances, and the like.

In 1947, brothers David and Julius Braun of New Jersey label DeLuxe Records made a trip to New Orleans, looking for undiscovered jazz and blues talent to record. Upon discovering Matassa’s studio, the Brauns realized they could save money by recording artists in New Orleans rather than taking them back to New Jersey. Two of the earliest hits to come from Matassa’s studio were “True,” by Paul Gayten, and “Since I Fell for You,” by Annie Laurie (a cover of the 1945 song by Buddy Johnson and his Orchestra, with his sister Ella Johnson on vocals). Gayten was the primary musical director/arranger (the term “producer” was not in common usage yet) at Matassa’s studios in the early days, followed by Dave Bartholomew and then Allen Toussaint. Harold Battiste and Wardell Quezergue also acted as de facto producers at some later sessions.

The Braun brothers returned to New Orleans a second time in 1947, before the Petrillo Recording Ban of 1948, to stock up on new material. This time they cut Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” one of several tunes recorded at Cosimo’s to be dubbed the beginning of rock and roll. J&M’s relatively primitive equipment included a Presto 28N disc-cutting machine that employed an acetate master disc to produce metal “stampers,” from which the records were manufactured. Unlike later technology, overdubs or corrections were impossible; if a musician made a mistake, the acetate disc was discarded and the musicians started all over again.

After their initial successes, the Braun brothers searched for other New Orleans acts worth recording and discovered Dave Bartholomew (born December 24, 1920 in Edgard, Louisiana), a trumpeter, writer, and arranger with big-band training. Bartholomew went on to lead many sessions at Matassa’s studio and, in 1949, met Lew Chudd, the head of Imperial Records, who was looking for more R&B talent to record. Chudd offered Bartholomew a position as his A&R (“artists and repertoire”) man in New Orleans. Local boogie-woogie pianist Antoine “Fats” Domino was one of Bartholomew’s first discoveries. On December 10, 1949, Bartholomew, Domino, and several other musicians gathered at Matassa’s studio to record “The Fat Man,” which fit new lyrics to the music of an older song, “Junker’s Blues.” “The Fat Man,” which took its title from a popular radio program, reached number one on the R&B charts. It launched both Domino’s career and the “golden age” of New Orleans R&B, reportedly selling 10,000 copies in 10 days in New Orleans alone before breaking nationally in January 1950. For the next decade, Domino used J&M and later Cosimo studios to create his string of chart-topping national hits.

The self-proclaimed inventor of the “Big Beat,” Bartholomew’s exacting musical standards led him to work regularly with some of New Orleans’s most talented musicians, including guitarist Ernest McLean, bassist Frank Fields, legendary drummer Earl Palmer, pianists Salvador Doucette, Huey “Piano” Smith, and James Booker, and saxophonists Lee Allen, Herb Hardesty, and Alvin “Red” Tyler. These same musicians, in various combinations, played along with others on the vast majority of songs recorded at Matassa’s studios over the next decade. Some of the hits recorded at J&M include Little Richard’s “Tutti Fruitti” and “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” by Lloyd Price (both of which have also been cited as seminal rock-and-roll recordings), “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” and “Tipitina” by Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd), ”Honey Hush” by Big Joe Turner, “The Things That I Used To Do” by Guitar Slim (Eddie Jones) and featuring a young Ray Charles on piano, “Jock-A-Mo” (better known as “Iko Iko”) by James “Sugar Boy” Crawford, “I Hear You Knocking” by Smiley Lewis, and several early hits by Fats Domino.

Matassa entered the recording industry at a transitional time. The major labels such as RCA, Columbia, Decca, and Capitol, mostly based in New York City, were slow to grasp emerging new sounds in blues, country, and rock and roll. Between 1955 and 1959, their market share declined from 78 to 44 percent, creating an opportunity for independent studios and labels like the ones started by Matassa. Their success was fueled by radio, which was still locally based and featured regional artists; radio and jukeboxes alike stimulated consumer demand for recordings. Seeing the success of DeLuxe and Imperial Records, entrepreneurs from independent labels including Specialty, Aladdin, Atlantic, Savoy, and Chess traveled to New Orleans, hoping to cash in on the abundance of local talent. Matassa engineered and recorded sessions for them all.

Cosimo’s Recording Studio

Matassa learned the basics of recording through trial and error, audio engineering journals, professional organizations, and personal contacts that included Bill Putnam of Chicago’s Universal Recording Studios and the legendary Tom Dowd of Atlantic Records. He made use of technical innovations that originated in motion-picture audio and telephony. Matassa bought his first tape recorder, an Ampex Model 300, in 1949. Though he continued to make technical improvements to his studios over the years, he was always slightly behind the times and did not move to stereo and multitrack recording until well after other studios had done so. Nevertheless, his careful maintenance of and attention to his simple but high-quality equipment produced excellent-sounding recordings. Matassa had a knack for microphone placement and according to musician Dr. John (Mac Rebennack), rarely changed input levels once they were set for a session. “He would set the knobs for the session and rarely moved anything,” Rebennack revealed in John Broven’s book, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans. “He developed what is known as the ‘Cosimo Sound,’ which was strong drums, heavy bass, light piano, heavy guitar and light horn sound with a strong vocal lead. That was the start of what eventually became known as the ‘New Orleans Sound.’”

In 1956, Matassa moved his studio to 523 Governor Nicholls Street and then, when the building next door became available two years later, to 525 Governor Nicholls Street. The latter had been a cold-storage warehouse for avocados; its cork-covered walls were ideal for a recording studio. “Great sound in there,” Matassa recalled for Gambit in 2006. He changed the name to Cosimo’s Recording Studio since, according to Matassa, “Cosimo’s” was what everyone had called the old studio anyway.

In addition to Fats Domino’s many hits, other well-known late 1950s and early 1960s singles recorded at Cosimo’s include “Lucille” and “Good Golly Miss Molly” by Little Richard, “Ain’t Got No Home” by Clarence “Frogman” Henry, “Let the Good Times Roll” by Shirley and Lee, “Sea Cruise” by Frankie Ford, “Mother-In-Law” by Ernie K-Doe, “Ya Ya” by Lee Dorsey, “It’s Raining” by Irma Thomas, “Fortune Teller” by Benny Spellman, and “Land of 1,000 Dances” by Chris Kenner. Throughout these years, Matassa increased his presence in the local music industry with several side ventures: He started his own label and distributorship, opened a pressing plant, and managed singer Jimmy Clanton, who had a number four pop hit with “Just a Dream” in 1958.

Around 1965, Matassa moved his studio yet again, this time to 748 Camp Street, and named it Jazz City. American tastes were changing, and suddenly the popularity of the Beatles and Motown artists made New Orleans R&B seem old-fashioned. The last major chart hits recorded at Matassa’s studio in 1966 included Lee Dorsey’s “Working in the Coal Mine,” “Barefootin’” by Robert Parker, and “Tell It Like It Is’ by Aaron Neville.

Several independent labels that had recorded at Cosimo’s went bankrupt and could not pay for their recording sessions. New Orleans banks, not sympathetic to the music business, refused to lend Matassa money. Eventually the Internal Revenue Service confiscated his studio for nonpayment of taxes and sold his equipment at auction in 1969. Matassa went on to engineer some early sessions for Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn at their new Sea Saint Studio in Gentilly. But he mostly retired from music and returned to the grocery business in the 1980s. Matassa’s Market is still run by his family today.

Cosimo’s Legacy

The original J&M studio was declared a historic landmark by the city and state on December 10, 1999, fifty years after the recording of “The Fat Man.” In October 2007, Matassa was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame and was also honored as a Grammy Trustee for his early contributions to popular music. In a September 24, 2010, ceremony, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum designated the original J&M studio as one of eleven historic American rock-and-roll landmarks. The studio is now a laundromat, though there are historical displays and photographs that commemorate the building’s storied history, and the original J&M marble skirt remains at the front entrance.

Matassa insisted his role was simply to record the musicians as accurately as possible. Though he saw little financial gain from his work (he estimated he lost as much as $200,000), he treasured his experiences working with such talented musicians. As Matassa reflected in the 2006 Gambit interview, “All through my career, the one thing I tried to do was be transparent. I heard them in the nightclubs, and just wanted to stay true to the original, to get what they did on record. I didn’t try to shape it—I just did my damnedest not to mess it up.”

Matassa passed away on September 11, 2014.