Voudou

Voudou, a synthesis of African religious and magical beliefs with Roman Catholicism, emerged in New Orleans in the 1700s and survives in active congregations today.

Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

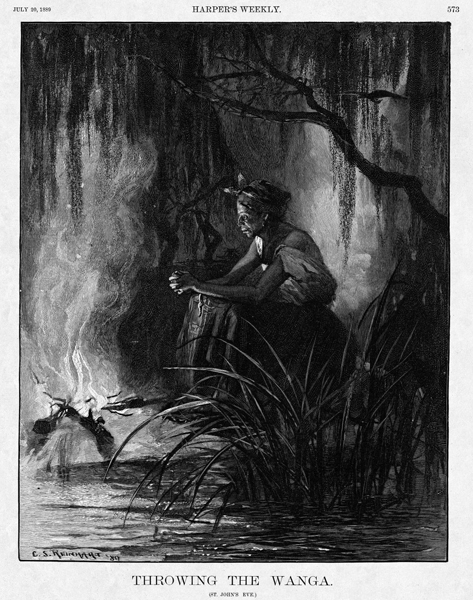

A black-and-white reproduction of an 1889 engraving entitled "Throwing the Wanga".

Voudou, a synthesis of African religious and magical beliefs with Roman Catholicism, emerged in New Orleans during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. From the colonial period until the present, New Orleans Voudou has incorporated other cultural influences. It has remained a serious religious faith for some people.

Voudou in Colonial Louisiana

The rudiments of Voudou arrived when the first enslaved West Africans were imported into French colonial Louisiana. As these newly arrived captives were instructed in the Roman Catholic faith, they found many familiar elements. The supreme being common to most African belief systems, for example, was analogous to the Christian God the Father. The deities who served as intermediaries between humans and the supreme being in Voudou resembled the Virgin Mary and the saints. Like the Afro-Catholic religions that developed in other New World colonies, New Orleans Voudou was characterized by a complex theology, a pantheon of deities and spirits, a priesthood, and a congregation of believers. The rituals, music, vestments, and sacred objects of the Catholic church probably seemed intrinsically familiar to many Africans, whose religious ceremonies stressed chanting, drumming, dance, elaborate costuming, and the use of spirit-embodying amulets. Through a process of creative borrowing and adaptation, slaves reinterpreted Roman Catholicism to suit their own needs.

In the early eighteenth century, as Frenchman Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz observed, enslaved Africans would “sometimes get together to the number of three or four hundred, and make a kind of Sabbath.” He also commented on their use of protective charms called gris-gris, derived from the word gregries in the Mende language. Court records document a 1773 case in which several slaves were tried for conspiring to kill their master by means of gris-gris. The word gris-gris is still used in New Orleans to denote an assemblage of magical ingredients employed by believers to attain love, control, success, protection, revenge, or luck.

Voudou in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana

During the 1791–1804 Saint Domingue revolution, a successful slave revolt that culminated in the founding of the Republic of Haiti, many refugees first sought asylum in Cuba and later settled in Louisiana. Nearly ten thousand arrived in New Orleans in 1809. These immigrants were more or less equally divided among whites, slaves, and free people of color. The Haitians of African decent, enslaved and free, brought their Vodou traditions with them. In Louisiana, they found ready acceptance among those who already adhered to some form of Afro-Catholic religion.

Authentic eyewitness reports of African-based religious and magical practices in New Orleans during the colonial period and the first decades of the American era are nonexistent. Accounts from the later nineteenth century show that important components of the Haitian religion had been lost. Ceremonies were less complex. The names of many Haitian Vodou deities, called lwa, did not survive. Instead, New Orleans Voudou devotees spoke of serving the spirits and the saints.

New Orleans Voudou also absorbed the beliefs of English-speaking, Protestant, “American negroes” imported from Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas during the interstate slave trade of the 1830s to 1850s. Unlike Louisiana slaves whose ancestors had originated in West Africa, these people were of Central African, Kongo origin. Instead of Voudou, they practiced hoodoo, conjure, or rootwork, a system of magic in which solitary practitioners perform rituals and formulate “mojo bags” and “roots” for individual clients. The Kongo influence is apparent in an emphasis on cemetery rituals and the use of human remains and “graveyard dust.” In New Orleans, gris-gris became conflated with these charms, with European pre-Christian magical artifacts, and with Christian sacred objects.

New Orleans Voudou was dominated by priestesses called “queens,” the most famous of whom was Marie Laveau. Voudou priests were referred to as “doctors.” The African-born practitioner Jean Montanée (c. 1815–1885), called Doctor John, was well known. These spiritual leaders served a racially diverse, mostly female, congregation. Weekly worship services took place in the homes of Voudou leaders. Their sanctuaries were characterized by spectacular altars, laden with statues and pictures of the saints, candles, flowers, fruit, and other offerings. Voudou ceremonies consisted of Roman Catholic prayers, chanting, drumming, and dancing. These rites were intended to call the spirits to temporarily enter into the bodies and minds of their worshipers and speak directly to the congregation. A shared meal followed the religious portion of the service. Voudou queens and doctors also gave private consultations, performed healing ceremonies, and formulated gris-gris.

The high point of the Voudou liturgical calendar was June 23, the Eve of St. John the Baptist, when a large ceremony took place on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain. St. John’s Eve coincides with the summer solstice, which in pre-Christian Europe was believed to be a time when the human world and the spirit world intersect. People kindled bonfires to attract good spirits and drive away bad ones, protect themselves from disease, and ensure a successful harvest. Believers also immersed themselves in sacred bodies of water supposed to be endowed with magical and medicinal virtues. The Roman Catholic Feast of St. John was grafted onto this night of pagan religious observance, and was introduced into Louisiana by French and Spanish colonists. It was adopted by people of African descent, who celebrated with bonfires, drumming, singing, dancing, ritual bathing, and a communal feast.

Voudou in Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Louisiana

By the end of the nineteenth century, repressive laws, police interference, and the disapproval of the Protestant churches drove New Orleans Voudou underground. Many of the religious aspects of Voudou were incorporated into the Spiritual Churches, founded in 1920 by Mother Leafy Anderson, an African American minister from Chicago. Spiritual Church services combined elements of Spiritualism, Pentecostalism, Catholicism, and Voudou.

Voudou’s magical component evolved into a New Orleans variant of hoodoo. New Orleans hoodoo resembles African-based magical practices found elsewhere in the American South, incorporating Catholic elements such as altars, candles, incense, oils, holy water, and images of the saints. Despite attempts at eradication by outsiders, and the alterations and disguises adopted by insiders, both the Voudou religion and the magical practices of hoodoo have survived in the fertile environment of New Orleans.

While the casual visitor to New Orleans sees only sensationalistic “voodoo and ghost” tours and “tourist voodoo” souvenir shops, authentic Voudou congregations continue to thrive in the city. Contemporary priests and priestesses, some of them initiated in Haiti, have established temples that serve a middle-class, mostly white, community of believers and endeavor to educate the public about Voudou.