Zion Harmonizers

New Orleans's Zion Harmonizers excelled in all forms of gospel music, from early a cappella spirituals to modern R&B.

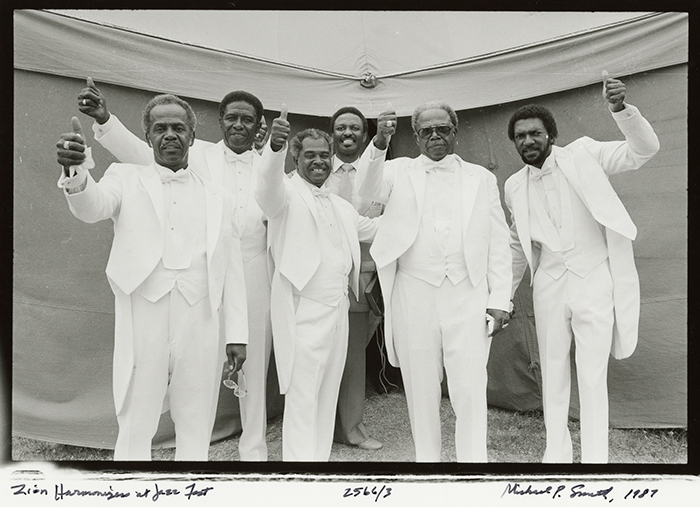

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Zion Harmonizers at Jazz Fest. Smith, Michael P. (Photographer)

The music of the Zion Harmonizers, while deeply rooted in the popular rise of modern African American gospel music in the 1920s and 1930s, plays a key role in the twenty-first century as a continuation of basic gospel traditions throughout southeast Louisiana and beyond. As New Orleans’s premier male gospel group, the Zion Harmonizers remain unique in two aspects: they excel in all forms of gospel—from early a cappella spirituals through traditional gospel hymns to more modern, rhythm and blues (R&B)-influenced “house rockers”; and they always view their mission from a grassroots perspective, touring only occasionally and recording almost exclusively for small, local labels. As gospel-music historian Lynn Abbott observed about the group in the 1990s: “While blessed with a spiraling international reputation, the Zion Harmonizers remain a pillar of the New Orleans gospel community. Most of their programs and song services are still conducted in small churches within a hundred-mile radius of the city.” They also have become a major draw at the Gospel Tent in the annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. In March 2011, the group’s longtime leader, Sherman Washington Jr., died at age 85, marking the end of one chapter and the beginning of another in the Zion Harmonizers’s history.

From Street-Corner Harmonies to Community Leadership

In 1939 the group began as a gathering of local teenagers in New Orleans’s Zion City neighborhood (more commonly known as Gert Town), a small sliver of the city that had already produced the much-celebrated Southern Harps, a well-known and admired female quartet that at one time included future gospel solo star Bessie Griffin. During the 1930s, close-harmony vocal groups were popular both in mainstream entertainment (such as Top 40 acts the Mills Brothers and the Andrews Sisters, who were specifically modeled after New Orleans’s own Boswell Sisters) and in the expanding world of gospel music (where the decade is considered a golden era that spawned a host of well-known groups, including the Golden Gate Quartet, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Fairfield Four, among many others). A group of neighborhood teenagers practicing close-harmony singing in their spare time was probably not unusual (and certainly continued through the 1950s doo-wop era), but in this case, one of the boys, Benjamin Maxon, happened to be the nephew of Alberta French Johnson, leader of the Southern Harps. Through that connection, the Zion Harmonizers became well schooled in traditional gospel music and gained recognition throughout the state at gospel concerts in the early 1940s, serving as the Southern Harps’ opening act.

Always seeking to improve their sound, the Harmonizers continued to recruit new voices, including Washington, who joined in 1942 while working alongside Maxon at the Higgins Shipyard in New Oleans. When Maxon answered the call in 1948 to devote his life to preaching full time, leadership responsibilities fell to Washington, who subsequently became the group’s driving force and international ambassador for more than six decades. Raised in the church, Washington was the son of a preacher who led a small congregation at the Morning Star Baptist Church in Thibodaux. Until the Korean War, Washington worked days in the tailor’s shop of Stein’s Clothing on Canal Street. Following a stint as truck driver during the war, he supported himself and his family for the next forty-three years by driving trucks for the Boh Brothers construction company. At the same time, he began a kind of public ministry over the radio waves, beginning with a show in 1956 sponsored by Schiro’s shoe store on local station WMRY, later switching to Sunday mornings on WYLD-AM, where his program—dedicated to local gospel records, anniversary and birthday announcements, and other news—became what music writer Keith Spera has described as “the gospel community’s town hall.”

A Fixture at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival Gospel Tent

Washington’s involvement with the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival—and especially his pioneering and shepherding the growth of the festival’s Gospel Tent—truly defined his and the Zion Harmonizers’ cultural legacy. With an instinct to popularize gospel music without diluting the gospel music experience, both Washington and Harold “Duke” Dejan, leader of the Olympia Brass Band, who felt the same way about New Orleans’s neighborhood brass band tradition, responded enthusiastically in the 1950s and 1960s to opportunities to record and concertize, recording general-audience albums and sometimes touring European festivals together. When the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival held its first small celebrations in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Washington not only signed up the Zion Harmonizers to sing but applied his own knowledge of New Orleans’s African American church and gospel communities to organize the gospel music tent, booking acts and managing performance schedules. At first, church leaders balked at the idea of their bands or choirs performing at a festival surrounded by all manner of music and fans who were free to drink beer and indiscriminately wander from stage to stage. “The preachers were against me,” Washington explained. Instead, he booked vocal quartets unaffiliated with any specific church. “They would tear the place up, pack it out,” Washington later testified. “We didn’t pay those preachers no mind. We just kept going.”

Eventually the Gospel Tent became, as one local writer described it, “The romping, stomping heart of Jazz Fest.” Church leaders eventually overcame their reluctance, and as the festival grew, the Gospel Tent had the opportunity to present a wide range of gospel acts. Even more importantly, it offered white audiences what was more than likely their first encounter with black gospel music. Festival founding director Quint Davis underscored Washington’s contribution: “In the early 1970s, not many white people had seen black gospel in its full glory. Even after jazz and blues had found their way to the front of the bus, metaphorically speaking, gospel music was still sitting in the back seats. So we made it our mission to change that, and without Sherman Washington, I don’t think we would have succeeded to the extent that we have. An enormous debt is owed him not only by the festival, but also by the gospel-music world at large.”

Following Washington’s death in 2011, responsibility for the Gospel Tent passed to other community leaders. Brazella Briscoe, a Zion Harmonizer for close to a quarter century, took over leadership of the group, determined to carry on just as the band had before by following the tenets of Washington’s trail-blazing inspiration.