African Americans in the Civil War

African Americans, both freed and enslaved, played critical roles in Civil War Louisiana.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

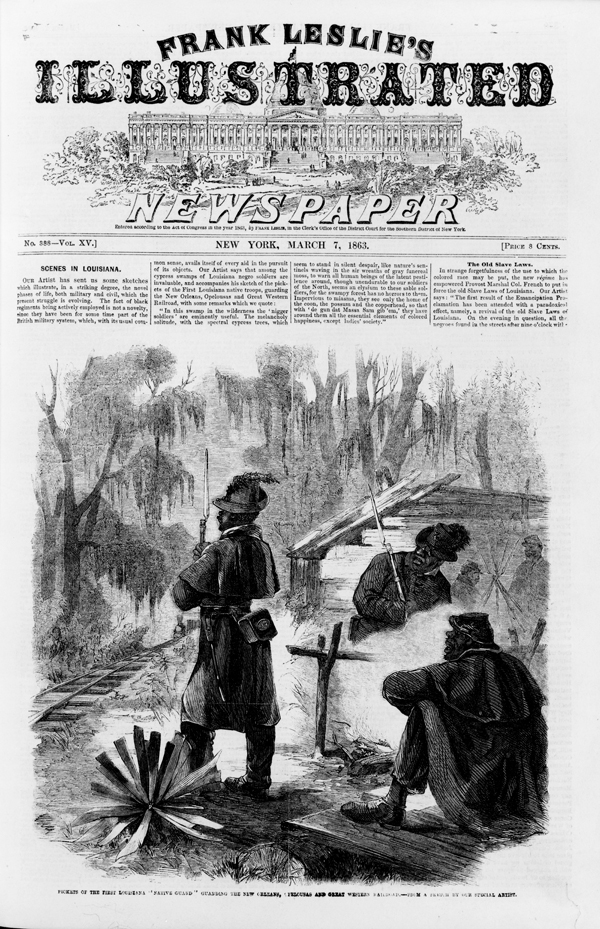

Pickets of the First Louisiana "Native Guard".

Historians have only recently begun to explore the role Louisiana’s Black population played in the Civil War, despite the fact that African American military service helped shape key legacies of the war. When the conflict began in 1861, neither the North nor the South embraced the idea that African Americans should serve in their respective militaries in any capacity except that of laborer. Indeed, fierce resistance to the idea of Black soldiering came from all levels of white society, from the lowliest private in the army to powerful generals and politicians. The act of arming, training, and assigning army rank to Black men was perceived as tantamount to acknowledging their worthiness for some degree of civil equality. Though one of the Union goals of the Civil War was emancipation, many white northerners opposed full civil equality for formerly enslaved people, let alone sharing equality in the ranks. Yet in the summer of 1862, events in Louisiana signaled a turning point in the creation of a Black soldiery. These events illuminated the revolutionary consequences of allowing formerly enslaved men to serve as citizen soldiers.

Native Guards in the Confederate Army

Ironically, the first Civil War army in which men of African descent served was not that of the Union, but the Confederacy. In April 1861, a group of influential free men of color met in New Orleans and formed a regiment called the Native Guards. Funded entirely by donations, these “defenders of the native land” organized several companies and even staged a grand parade down Canal Street. Historians disagree about the motivations of the men who raised this regiment. Some suggest that the Afro-Creole leaders acted out of fear, that they created the Native Guards to assuage the anxieties of those who saw free Black people as a dangerously disloyal population in the Confederacy. Other historians argue that the Native Guards reflected the economic and cultural ties Black elites shared with their white counterparts. They contend that Afro-Creoles hoped military volunteerism might earn them full citizenship in the Confederacy, something denied to them under the flag of the United States. A third assertion, far more dubious, made by neo-Confederate historians suggests that the Confederate Native Guards represent a kind of proof that the Civil War was not about slavery, or at the very least, that the Confederacy did not hew to the ideology of white supremacy.

Whatever the motivations of the Native Guard’s leaders, neither the state of Louisiana nor the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, knew what to do with these Black soldiers. Not until the loss of New Orleans was imminent were weapons issued to the Native Guards. With the Union Navy steaming up the Mississippi River toward New Orleans, Gen. Mansfield Lovell ordered the free Black regiment to keep peace in the city while his rebel army plundered it of anything portable enough to take with them in their retreat. Left behind by their comrades, the Native Guards quietly dissolved as the Union Adm. David Farragut’s squadron arrived at the levee on April 26, 1862.

The Native Guards in the Union Army

Ultimately, the greatest contribution of these so-called “Black Confederates” was that they served as the basis for a new Union version of the Native Guards. In the summer of 1862, a delegation of its officers, including Octave and Henry Louis Rey, Eugène Rapp, and Edgar Davis, met with Gen. Benjamin Butler in New Orleans to swear their loyalty to the Union and tender their services to the army. Sharing many of the racial prejudices of his peers—and all of their political objections to Black soldiers—Butler initially declined the offer of the Native Guards’ officers. He changed his mind when he realized the scarcity of manpower in southeastern Louisiana and the probability of Confederate counterattack.

Unfortunately for Butler, he could not act immediately. The biggest impediment to forming a Black regiment was the question of its legality, followed closely by Butler’s genuine concern that the Lincoln administration might rescind his order. Earlier efforts at enlisting Black troops, like Gen. David Hunter’s ad hoc regiment of formerly enslaved men in South Carolina, ran afoul of legal and political obstacles. Further, their lack of discipline decreased the likelihood of Black soldiers gaining acceptance in the Union Army. In the summer of 1862, however, the most vexing issue was the ambiguous legal status of runaway slaves. Moreover, the Native Guards’ offer came at a time when the federal government was loath to anger border slave states such as Maryland and Kentucky. Loyal slaveholders feared that an army of Black men would encourage enslaved people to rebel.

The key legal fact, however, was that under the Confederates, the Native Guards were all free men of color, not enslaved men. When the US Congress passed two acts in July 1862 that authorized commanders to enlist free Black men, Butler quickly raised a single provisional regiment of Union Native Guards. This call to arms elicited such an overwhelming response from New Orleans’s free Black population that it required the creation of not one but three regiments. (It should be noted, however, that many of the men who enlisted in the Confederate Native Guards chose not to fight for the Union.) Along with the 1st Kansas (Colored), which had been raised in a free state, these units would become the first permanent Black regiments in the US Army. At least in theory, free men of color made up their ranks, though it is likely that some, perhaps many, runaway slaves lied about their freedom in order to enlist.

Butler intended to use the Native Guards for garrison duty and labor, freeing up his white regiments for combat duty. Many Black soldiers became discouraged by this turn of events, as well as the mean-spirited treatment they received from white soldiers. Most of the Native Guards spent the rest of 1862 manning the prisoner of war camp and defenses of Ship Island off of the coast of Mississippi. Others guarded the passes between Lake Pontchartrain and the Gulf of Mexico at Forts Macomb and Pike. By placing the Native Guards in these backwaters, Butler avoided sending a Black regiment into slave country on the eve of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Though perhaps even more hostile to the use of Black troops, Butler’s successor, Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, would ultimately supply the Native Guards with an opportunity to prove their devotion to the Union. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, removed the legal obstacles to recruiting runaway slaves. Though the executive order potentially paved the way for raising more regiments, Black soldiers had not yet been allowed to demonstrate their effectiveness on the battlefield. They would get their chance under General Banks.

On May 27, 1863, the First and Third Regiments of the Native Guards took part in a desperate assault on the enemy works at Port Hudson, during Banks’s poorly led campaign against the Confederate bastion. While their attack failed, the performance of the Native Guards silenced many critics and proved that Black soldiers were just as willing to die for their country as their white comrades. Like the white troops they fought beside, the Native Guards took enormous casualties at Port Hudson. Among the dead was Lieutenant André Cailloux, who led his fellow New Orleans Creoles forward in both French and English. An illustration depicting his funeral procession appeared in Harper’s Weekly in August 1863, and did much to influence national opinion in favor of the recruitment of Black troops.

In the second half of 1863, the status of Black soldiering in the Union Army underwent profound change, and again, events in Louisiana led the way. The new legal status of runaway slaves as “contraband of war” made the vast majority of African Americans in the South eligible for recruitment, but this infusion of manpower also bred resentment in the Army. General Banks begrudgingly accepted Black soldiers, but he could not countenance Black officers who might have authority over white troops. Starting in the summer of 1863, Banks and his subordinates began a series of reviews that resulted in the expulsion of almost all the Afro-Creole officers who had been instrumental in raising the Native Guards, even those who had bravely led troops at Port Hudson. Among the few who remained was Charles Sauvinet, who would go on to be the longest serving Black soldier in the Civil War, leaving the Army with the rank of captain in June 1865.

The Union advance into southern Louisiana allowed many enslaved people on both sides of the battle lines to escape, and New Orleans became a popular destination for those seeking their freedom. As early as November 1862, General Butler established Camp Parapet just above New Orleans on the Mississippi River as a training depot for Black troops. It remained an important recruiting center throughout the war. Black regiments continued to play an important role in Civil War Louisiana, including during the Red River Campaign of 1864.

Black soldiers also helped define freedom, both during and after the war. More than 180,000 Black troops in all served in the Union Army. While in uniform, many learned important skills such as literacy and gained knowledge of the political process. After Appomattox, these veterans formed the core of a Black leadership class in the postbellum South. Most important, their voluntary military service, steeped as it was in the tradition of republican values, decisively swayed Reconstruction-era politicians to grant Black men citizenship and the ballot. It is easy to argue that neither the Fourteenth nor the Fifteenth Amendment would have passed in their current form had not Black soldiers fought for rights with the Union.