Auseklis Ozols

Artist and teacher Auseklis founded the New Orleans Academy of Fine Arts in 1978.

Courtesy of Auseklis Ozols

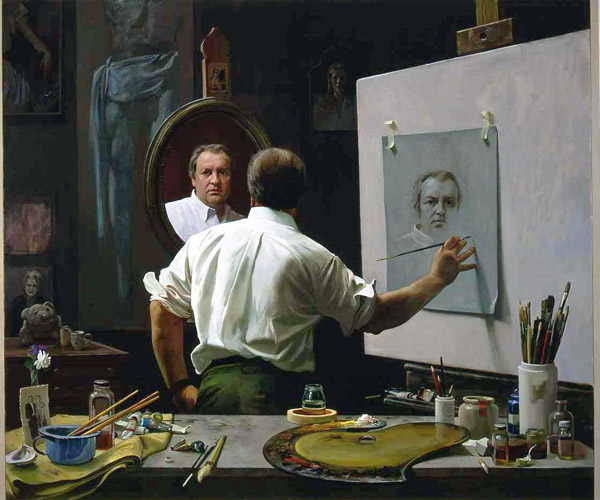

Self Portrait. Ozols, Auseklis (artist)

Lpressive painting—with all its required transcendent abstraction—is good drawing. As an artist, Ozols is captivated by the beauties of nature found in simple flowers, in the nuances of a figure, or in the misty morning light of a hazy Louisiana swamp.

Born on September 22, 1941, in Strenci, Latvia, Ozols emigrated to the United States in 1949 after his family fled the advancing Soviet army during World War II. The Ozols family also survived imprisonment in the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau, Germany. Ozols grew up in Trenton, New Jersey, and went on to graduate from three universities in Philadelphia: the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Tyler School of Art at Temple University. He moved to New Orleans in 1970 to design an exhibition space at the New Orleans Museum of Art. What was to be a brief stay turned out to be permanent. He met and married and a New Orleans woman, Gwendolyn Laan, and the city became his home. Ozols established a studio in New Orleans, but the artist, a three-time winner at juried exhibitions sponsored by the National Academy of Design in New York City, continued to spend time in Philadelphia painting, creating murals and completing commercial art assignments. By the late 1970s, Ozols and his wife decided New Orleans was in need of an art school that stressed the classical and more traditional academic methods.

In 1978, Ozols opened a small art school over an Italian restaurant at 3218 Magazine Street in uptown New Orleans. In 1980, a student of his, Dorothy Coleman, offered Ozols an entire three-story Victorian building at 5256 Magazine Street as a new home for the New Orleans Academy of Fine Arts, where the institution continues to operate. Coleman later became Ozols’s partner and the school’s president. The school also houses the Academy Gallery, a teaching adjunct where faculty and local and national artists exhibit their work. With classes in drawing, painting, sculpture, and photography, students must first master various aspects of drawing, from basic geometric shapes and one-point and two-point perspectives to ancient sculpture, human muscle and skeletal structure, and then life drawing from the figure. Such coursework may continue for a year or more before students begin painting.

“Drawing is a search, a looking into the wonderful mysteries of creation and it is a vehicle for personal expression,” Ozols said. “Whatever we have in ourselves comes out in that drawing. It’s miraculous. You can’t learn how to paint without learning how to draw. It’s as simple as that. Drawing is the substructure, the foundation of all visual arts. It is essential. It’s like building a cathedral. You have to build the foundation first, then comes the walls and eventually all the music and decoration and expression come afterwards. But most of all, it has to stand on a foundation. That foundation is drawing.”

Ozols describes his style of painting as romantic realism. “I was trained to paint from life, as the French call en situ, and realize now that the human eye sees completely different than the eye of the camera.” In paintings such as The Witness and City Park at Dawn, Ozols’s work reflects the realism of his training at the Pennsylvania Academy and the influences of Thomas Eakins, the world-renowned nineteenth-century realist who headed the Pennsylvania Academy for many years. While at the Academy in the 1960s, Ozols studied with well-known contemporary artists such Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Lipchitz, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Motherwell, and other artists in the abstract expressionist movement. “We exchanged ideas on aesthetics and I found that a lot of them fell short,” he said. “People think I hate modern art, but I love an abstract painting as well as anyone else, but I know what the word abstract means. To abstract something means to get to the essence of the essential characteristics of something. That takes study and a lot of knowledge. It’s not something quick or facile. If any artist works honestly and there is expression, it is going to come out. It’s something you cannot force or fake.”

Ozols expressed his thoughts about the art movements of the 1960s: “After many years of following contemporary innovation and agonizing over ‘style’ and ‘personal statement’ and ‘social consciousness,’ I realized what my true métier was, to look at God’s creation and record it to the best of my ability with my God-given gifts and to share it with my fellow man. I studied with the most notable and well-known painters and aesthetic philosophers of the sixties, and was constantly aware of all new ‘isms’ to eventually realize that all ‘isms’ become ‘wasms.’ Harold Rosenberg lectured at Tyler, Buckminster Fuller at Penn. My grad school painting professor Roger Anliker was Andy Warhol’s roommate at Carnegie, Marcel Duchamp and Jacques Lipchitz lectured at the Academy in the ‘60s. In 1962 my teacher Walter Stuempfig brought me to Edward Hopper’s studio where I met Malcolm Forbes, a major collector of Stuempfig’s work. All of this is not to name drop, but to record my awareness of the new schools of thought and painting at the time.”

Ozols has received numerous honors, including the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ coveted Cresson European Traveling Scholarship in 1964 and the Thouron Prize for Composition in 1963. He also received the New Jersey State Museum Purchase Prize in 1965; the National Academy of Design’s Julius Hallgarten Awards in 1963 and 1964; the Delgado Society Award at the New Orleans Museum of Art; the Arts Council of New Orleans’s 2009 Community Arts Artist of the Year award; and the New Orleans Museum of Art’s Love in the Park Award in 2008.

In addition to painting portraits of Louisiana Governor Mike Foster and Louisiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Pascal Calogero, among others, Ozols has painted murals in the Louisiana Governor’s Mansion in Baton Rouge; St. Rose de Lima Church in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi; and the Windsor Court Hotel in New Orleans.

His paintings are included in numerous private and public collections, including the Old State Capitol Museum in Baton Rouge; the Baton Rouge Art League; the New Orleans Museum of Art; Loyola University in New Orleans; Tulane University in New Orleans; the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton; Temple University; the Rujiena Art Museum in Latvia; The Historic New Orleans Collection; the New Orleans Carnival krewes of Hermes and Rex; the Academy of the Sacred Heart in New Orleans; and the Beauregard House in New Orleans.