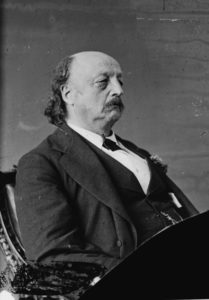

Benjamin Butler

Gen. Benjamin Butler's tenure as commander of the Union occupation forces in New Orleans in 1862 was so brutal that residents labeled him "Beast."

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

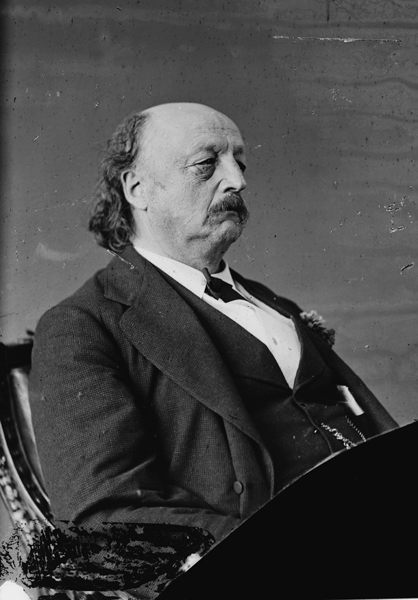

Hon. Benjamin Butler, Senator from Massachusetts. Unidentified

General Benjamin Butler’s behavior as commander of Union occupation forces in New Orleans for only eight months in 1862 spawned an evil, enduring reputation among southerners that was rivaled during the Civil War only by that of Gen. William Sherman after his scorched-earth march across Georgia. Labeled “Beast Butler” for his brutish physical appearance and for his harsh policies in New Orleans—especially his infamous “Woman’s Order”—Butler is characterized by historians as a P. T. Barnum-type, headline-grabbing showman for his tumultuous military and political life.

Early Life

Benjamin Franklin Butler was born on November 5, 1818, to John Butler and Charlotte Ellison Butler in Deerfield, New Hampshire. The elder Butler served under Gen. Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans and died around the time of Benjamin’s birth. As a child, Butler was unhealthy and disfigured by a drooping eyelid and severe strabismus. His mother, a devout Calvinist, insisted on a good education for her son so that he could read and perhaps become a preacher. Butler, though, had military aspirations and sought an appointment to West Point. When this plan fell through, he obliged his mother by attending the Baptist Waterville College in Maine. Considered a rabble-rouser in the conservative school, Butler shied away from religion as a profession and instead charged ahead into law—a business that he felt matched his temperament. At twenty-one, he was admitted to the Massachusetts bar and soon after was certified to practice at the US Supreme Court. On May 16, 1844, Butler married Sarah Hildreth, a noted physician’s daughter with whom he eventually had four children.

As an aggressive attorney with a reputation of defending felons as well as downtrodden millworkers, Butler joined the Democratic Party and embraced the rough-and-tumble atmosphere of politics. He served in the Massachusetts state legislature and narrowly lost the governor’s race in 1859. His political ambitions led him to support Jefferson Davis at the 1860 Democratic National Convention.

Civil War

With almost no military experience, Butler nevertheless viewed the looming Civil War as an opportunity to enhance his personal status and wealth. Using his political connections, he finagled a position as brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia and with his troops was ordered south to the vicinity of Washington, D.C. He immediately became embroiled in controversy because of his unauthorized activities, impertinence toward authority, and disregard of military procedures. President Abraham Lincoln, however, realizing Butler’s popularity in the North’s Democratic Party, promoted him to major general and approved his leadership in the campaign to capture New Orleans.

To his dismay, Butler had no part in the actual capture of New Orleans, an honor that went to US Navy Admiral David Farragut after he bombarded and ran his flotilla past Forts Jackson and St. Philip near the mouth of the Mississippi River. Several days later, on the evening of May 1, 1862, Butler disembarked as military governor of the largest city in the South. From the docks, he marched behind a drum corps playing “Yankee Doodle” to the US Custom House, where he began his notorious reign over a petulant citizenry.

Butler’s immediate task was to overcome the passive resistance of the mayor, John T. Monroe, and his administration. He continued the martial law established by Confederate forces that had retreated north to Camp Moore, and offered to permit the city government to operate most municipal activities. Monroe balked at every order and was soon arrested along with his chief of police, John McClelland, and sent to Fort Jackson for obstruction of federal authorities.

From the outset, New Orleans citizens treated Union soldiers with contempt and scorn. Women, in particular, verbally abused troops, sang secession songs in their presence, and worse. Troops were spit on and chamber pots were dumped from balconies onto passing soldiers. The deteriorating situation prompted Butler to issue his infamous General Order No. 28, which read:

New Orleans, May 15, 1862. As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling themselves ladies) of New Orleans in return for the most scrupulous non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall by word, gesture, or movement insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation.

The perceived insult spread across the country and the Atlantic Ocean like wildfire. In the South, nothing was more sacred than the honor of a woman. The order was also unpopular in the North, and the act was even admonished in the British House of Commons and in France. It was eventually a factor in Butler’s removal.

Butler’s job in New Orleans was unenviable. Thousands of citizens, including slaves, were hungry and without means of support. Lacking a functioning government, the city was filthy and ripe for epidemics of infectious disease. Crime was rampant; seditious behavior, including the threat of assassinations and smuggling, was everywhere. Though heavy-handed in his approach, Butler was effective in addressing these issues. Citizens were fed with troop rations and with Butler’s personal funds. Streets and canals were cleaned regularly, and crime rings were broken up.

On the other hand, Butler allowed his brother illegal trade advantages in the city that made the brother (and likely the general himself) rich. In addition to “Beast,” Butler also earned the nickname “Spoons,” in reference to his alleged habit of pilfering the silverware of commandeered Southern homes where he was quartered. He fanned the flames of hatred by prohibiting public prayer for the success of the Confederate Army and closed Episcopal churches for refusing to pray for President Lincoln. As a result, a steady flow of complaints against Butler flowed into Washington. His superiors’ tolerance levels were finally exceeded when Butler ordered all foreigners in the city to take the oath of allegiance, which constituted a violation of international law. British, French, and Dutch consuls were outraged, and Lincoln recalled Butler. He left New Orleans on December 16, 1862. The Daily Picayune on that date covered the event in one sentence: “We learn that General Butler and staff will leave the city at 10 o’clock this morning for the North.”

Because Butler was politically important to Lincoln in the upcoming 1864 election, he was offered the command of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina in late 1863. His continuing ineptness finally resulted in the end of his military career.

Postwar Civilian Life

After the war, Butler went on to serve five terms as a congressman from Massachusetts and later as that state’s governor. He was involved in the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson and authored progressive civil rights legislation that failed to pass. He was considered a brilliant lawyer, a political firebrand, and an incompetent soldier. The reputation he forged in New Orleans outlived him. He died January 11, 1893, and was buried at the Hildreth Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts.