Classical Music in Louisiana

Louisiana has boasted a rich classical music traditional since early European exploration and settlement.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

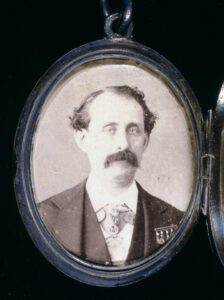

This locket holds a portrait of Louis Moreau Gottschalk. At concerts and public appearances, the composer and pianist proudly wore the many honorific medals and jewels (visible here) bestowed upon him by adoring fans among the European nobility.

Louisiana justifiably boasts of a rich classical music tradition that dates from the earliest days of European settlement, and music education was always an integral part of the state’s cultural patrimony. While little actual documentation and precious little music from the colonial period survives, it is evident that music was an integral part of eighteenth-century society in both rural and urban areas. Documentation and ongoing scholarly activities clearly indicate that the classical musical tradition was exceptional in the nineteenth century. Classical music was also a unifying element of the many ethnic groups that settled Louisiana. By the twentieth century, the strength and diversity of classical music were clearly manifested in the number of organizations that sponsored performances, offered music education, and increased documentary studies on the history of classical music in the state.

Classical Music in Colonial Louisiana

When Hernando de Soto and his fellow Spanish explorers traveled the Mississippi River Valley in 1541, it is reasonably safe to presume they followed the practice of singing the Salve Regina on Saturdays. Thus, not only were they the first Europeans in the region, but they also first introduced European music to what would later become known as the “vast country of Louisiana.” The more formal introduction of European music tradition into the valley began through the two crusading arms of empire in the early eighteenth century: the military and the Catholic Church.

The Capuchin school, founded in 1725 by Raphael de Luxembourg in New Orleans, firmly established music education in Louisiana, and the Ursuline nuns who arrived two years later reinforced this training. Today, the sole known surviving corpus of colonial music in the Mississippi River Valley is a manuscript collection of works by the most popular French and Italian composers of the day, which was presented to the Ursuline nuns in 1754. The parish church of St. Louis employed Pierre Fleurtel, a musician and schoolmaster, to develop the music program in 1725. The following year, he was joined by François Saucier, whose grandfather served as organist of St. Eustache in Paris. The Spanish continued and enlarged upon the French colonial musical tradition. Vicente Llorca, who had served under Bernardo de Galvez (governor of Spanish Louisiana) during 1781, joined the musical staff of the St. Louis parish church, specifically to “compose music in the Spanish style.” Serving as a church musician until 1803, he was the first composer known to have worked in Louisiana.

The earliest opera performed in New Orleans was Andre Ernest Grétry’s Sylvain, presented on May 22, 1796 at the Théâtre St. Pierre, which had opened in October 1792. Since that date, New Orleans has had the advantage of operatic performances on a yearly basis and has played a unique role in the development of opera in the United States. In the final years of the colonial period, 1800–1803, Joseph Arquier, a French composer of comic opera who received encouragement from Grétry, lived and worked in New Orleans. According to nineteenth-century European writers, his opera Le desert ou l’oasis is believed to have been performed in New Orleans in 1802.

Likewise, Louisiana had an impact on European music as early as 1725, when Native American chiefs from the Mississippi River Valley visited Paris. Among the Europeans hearing their music and dance presentations was Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764). In 1728, he published Les Sauvages for keyboard. Based upon the melody and rhythms that he heard the Indian musicians perform, it became one of the most popular pieces for keyboard in eighteenth-century France. Later, he used it as the basis for the fourth act of his opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (1735).

Classical Music in Nineteenth-century Louisiana

With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, New Orleans transitioned from being a colonial city to an American city, whose musical tastes were exceptionally broad in scope. Instrumental music of Czech (Jan Ladislav Dussek); French (Ignaz Pleyel, Pierre Gaveaux, Martin-Pierre Dalvimare); German (Friederich Kalkbrenner, Daniel Gottlieb Steibelt); Italian (Domenico Cimarosa, Muzio Clementi, Giovanni Paisello, Giovanni Battista Viotti); Moravian (Franz Krommer, Pavel Wranitsky); Portuguese (João Domingos Bomtempo); and Spanish (Antonio Martín y Soler) composers was heard in New Orleans during the territorial period (18033–1812) and the early years of statehood. The presence of such a variety of international composers set the scene for the development of music in the region.

As clouds of social and political discontent gathered over St. Domingue in the late 1700s, refugees from that island to New Orleans further strengthened the musical personality of the city and region. When the vast majority of the refugees arrived in 1809, the city grew radically not only in size but in musical sophistication. In addition, as Germans arrived in New Orleans, they brought with them their love of music. By the mid-nineteenth century, New Orleans could boast several German singing societies, and by the end of the 1800s the city hosted the national convention of all North American German singing societies in magnificent Saengerfest Halle, which was built especially for the occasion. Scattered programs and annotations in books indicate that German singing societies were not limited to New Orleans. The Mississippi River carried performers from New Orleans to Baton Rouge and points further north in other states. While most research has focused on the musical activity of New Orleans, there is ample evidence that the same music was disseminated throughout the state and Mississippi River Valley.

The international nature of New Orleans musical tradition was also inclusive. Free people of color in New Orleans enjoy the credit for establishing the Philharmonic Society. Boasting some one hundred instrumentalists, it was one of the first nontheatrical orchestras in New Orleans and was also integrated, as it included white musicians. Not only did the Philharmonic Society perform works by free people of color, the group presented the standard orchestral repertoire of the day. Similar musical organizations persisted well into the late nineteenth century.

The contributions of New Orleans-born composers such as Basile Barés, Edmund Dédé, the Lambert family, and Samuel Snaer were recounted in detail in Music and Some Highly Musical People, published by James M. Trotter in 1878. Trotter’s work is generally recognized as the first music history of the United States.

Composers

While the musical wealth of New Orleans and the surrounding region nurtured several composers, the careers of two boys, relatively close in age, who grew up in the Vieux Carré during the height of the “Golden Age” of New Orleans music attest to the vast pool of musical talent in the region. Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) went to Paris to study at age 12. Initially, he had a less than receptive greeting by musical circles in Paris. He eventually gained acceptance and became arguably the first American pianist and composer to enjoy international fame. He was also among the first American or European pianists to enjoy an intercontinental career. He exploited the trend of employing nationalistic themes and rhythms, as did other composers of the day. However, Gottschalk’s chief importance is his careful incorporation of Caribbean rhythms and Creole folk melodies into his music.

Ernest Guiraud (1837–1892) was born in New Orleans to Jean-Baptiste-Louis and Adèle Croisilles Guiraud, who had moved from France to work for the Théâtre d’Orléans. Ernest received his early musical training with his parents. Like Gottschalk, he went to Paris to continue his musical education. In contrast to Gottschalk, however, he was quickly admitted to the inner circles of Parisian musical life. Like his father, he won the coveted Prix de Rome in 1859. Guiraud enjoyed a multifaceted career. A friend of Georges Bizet, he rehabilitated a failed Carmen upon Bizet’s death by adding the haunting recitatives. As a teacher at the Paris Conservatory, his composition students included such luminaries as Paul Dukas and Claude Debussy. While his conservative musical compositions found favor with audiences, his Traité pratique d’instrumentation (1890) remained a basic textbook for nearly fifty years.

Music Publishers

During the nineteenth century, the enormous musical activity of New Orleans was reflected in the local music publishing industry. Music historians credit Emile Johns with being the first music publisher in New Orleans, as well as the first performer of a Beethoven piano concerto in the United States, which he performed in New Orleans. Born in 1798 in Cracow, Poland, he arrived in New Orleans in 1819 to pursue a musical career. Johns was well known in European musical circles; Chopin dedicated his opus 7 mazurkas to “Monsieur Johns de la Nouvelle-Orléans.” In the early 1830s, Johns began publishing sheet music. One of his earliest publications was his own Album Louisianais, a co-imprint with Pleyel of Paris, c. 1833. He quickly expanded his printing business to include law books. In 1846, he sold his business to W. T. Mayo, who continued his work as a music publisher. In 1954, Mayo sold the business to Philip P. Werlein, a German immigrant. Establishing himself as a music teacher and subsequently opening a music business in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in the early 1830s, Werlein moved to New Orleans in the early 1850s.

Fellow German Louis Grunewald immigrated to the United States in 1852 and established himself as a musician and music store owner. Like Werlein, he opened his own theater (Grunewald Hall) and added the title of impresario to his credits. The German musical journalist, pianist, and conductor Hans von Bülow praised the acoustics of Grunewald Hall. The brothers Armand and Henry Blackmar established a music publishing company in New Orleans in 1860. Both were music teachers prior to establishing their music publishing company. During the Civil War, the Blackmar firm issued a large number of patriotic compositions, among them the “Dixie War Song,” the “Southern Marseillaise,” and “Beauregard Manassas.” During the ward, Henry Blackmar moved the company to Augusta, Georgia, while Armand continued to publish in New Orleans until Union authorities forced him to cease work.

The 1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial, held in New Orleans, boasted an exceptionally strong musical component. Best known was the Mexican brass bands that captured the hearts and imagination of the city’s music lovers. The Junius Hart Music Company issued a “Mexican Series” of sheet music that presented the Mexican band’s music in piano transcriptions. Though other local publishers did so as well, Hart’s catalogue was particularly large and significant. During the nineteenth century, New Orleans was home to music publishers and to thriving businessmen such as Jean Schweitzer who printed and sold, both in New Orleans and Napoleonville, opera libretti to satisfy the public’s appetite.

Classical Music in Twentieth-century Louisiana

The classical musical tradition in Louisiana continues to develop in the twentieth century, as evidenced by performing arts organizations and ongoing educational efforts. Louisiana followed national trends with organizations forming alliances with artist management agencies to bring live classical music to the state. Major benefactors gave generously to the performing arts. The development of regional arts councils throughout the state played a major role in the dissemination of classical music, as well as other art forms. As the population has shifted within the state, vibrant new performing arts organizations have been established. Neighborhood organizations, particularly churches, have established reputable concert series. Additionally, the growth of public broadcasting, both television and radio, has raised the public’s awareness of classical music throughout the state. While performing arts organizations have carefully nurtured outreach activities, those designed for children have been particularly creative. In conclusion, increased accessibility to classical music has been a distinction of twentieth-century Louisiana.

Performing Arts Organizations

The twentieth century saw the growth of a variety of institutions that sponsored music programs throughout the United States. The Community Concert movement developed in the 1920s to address the growing demand for concerts in a cost-effective fashion. In 1927, in an effort to finance such programs, associations in the Great Lakes region and in the eastern states developed a concept to address this issue. The concept itself was simple: raise the money first, and then hire the artists. The idea worked and ensured the presentation of first-quality artists throughout the country. Eventually, it developed into the Community Concerts, and this “organized audience” plan spread and gradually became the largest network of performing arts presenters in the country. The movement continued to grow in spite of the Great Depression, and after World War II expanded even faster. Part of the reason for its success was that the Community Concerts program was a division of Columbia Artist Management, which was designed to bring the performing arts to smaller communities. Louisiana was no exception. The Community Concerts Association had chapters not only in the larger metropolitan areas but in smaller cities and towns. Chapters arose in Baton Rouge, New Iberia, and New Orleans. In the 1990s, the Community Concert movement and Columbia Artists Management separated. Fortunately, the series continued in communities on its own, employing the same basic concept, and regional arts councils also arose around the state.

Today, the Shreveport Arts Council, the Northeast Louisiana Arts Council, the New Orleans Arts Council, the Arts Council of Central Louisiana, the Arts Council of Baton Rouge, the Houma Regional Arts Council, the Acadiana Arts Council, and others are active in promoting the arts in general throughout Louisiana. New performing arts societies have begun to develop, such as the Performing Arts Society of Acadiana and the Jefferson Parish Performing Arts Society. Historically, many of the presenting organizations credit their existence to at least two particular situations. Organizations such as the New Orleans Friends of Music remain all-volunteer organizations. Others, such as the New Orleans Opera Guild, benefited from the remarkable generosity of one individual, Mrs. E. B. “Nella” Ludwig.

The universities located throughout the state also continue to hold their own concert series, which are of tremendous value not only to the institutions themselves but to the community as a whole. In addition to presenting student recitals and productions, the universities sponsor nationally and internationally acclaimed artists. As the twentieth century progresses, and especially as costs associated with concert presentation rose, churches (usually with superior acoustics) provided a venue for numerous performers. The series are not limited to larger churches, such as St. Mark’s Cathedral in Shreveport, Christ Church Cathedral in New Orleans, and St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, but appear in countless other churches throughout the state.

Symphony Orchestras

In the 1900s, symphony orchestras grew both in number and in operating budgets throughout the state. For many years, the state’s flagship symphony was the New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony, established in 1936. Financial difficulties forced it to close in the early 1990s. In September 1991, members of the former New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony established the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra as the only full-time professional orchestra in the Gulf South. It is the only musician-owned and -operated professional symphony in the United States. As the twentieth century progressed, symphony orchestras were established throughout the state. The Louisiana Symphony Orchestra Association counts seven member orchestras: Acadiana, Baton Rouge, Lake Charles, Monroe, New Orleans, Rapides, and Shreveport.

New Endeavors

During the second half of the twentieth century, musical activity in Louisiana not only increased but entered into new endeavors. Two such examples are the Musical Arts Society of New Orleans and the New Orleans Musica da Camera. Established in 1980 as the New Orleans Institute for the Performing Arts, the Musical Arts Society of New Orleans has striven to provide students and teachers in the area with master classes, workshops, and performances by acclaimed performers. During the summer, the Musical Arts Society holds the New Orleans Keyboard Festival, featuring master classes, lectures, and recitals. In 1989 the program was enlarged to include the New Orleans International Piano Competition, which is currently regarded as one of the finest showcases for young pianists.

As interest developed throughout the United States in the performance of early music, Milton G. Scheuermann, Jr., established New Orleans Musica da Camera by in 1966. Today, it is the oldest surviving early music organization in the United States. Specializing in music of the tenth through the eighteenth centuries, in addition to its regular performances, the organization conducts workshops, and presenting Continuum, the oldest continually broadcast radio program devoted exclusively to early music in the United States.

Music Education

By the end of the twentieth century, Louisiana could count numerous sons and daughters who have gone on to the international stage, such as premier danseur Royes Fernandez, pianist-composer-arranger Genevieve Pitot; composers Roger Dickerson and Dino Constantides; choreographer Peter Genero; singers Norman Treigle, Ruth Falcon, and Shirley Verret; and harpsichordist Skip Sempé.

None of the above would have been possible without a university music education system. Several of these university music education programs can trace their origins to the nineteenth century. The Hurley School of Music at Centenary College in Shreveport originated in 1852, when the college hired its first full-time music instructor. The music department of Tulane University dates from the early twentieth century. Louisiana State University’s School of Music has been accredited since 1931 by the National Association of Schools of Music. The LSU School of Music boasts one of the oldest university opera companies in the nation. Since the 1930s, graduates of the program have enjoyed distinguished careers not only at the Metropolitan Opera but also at major opera houses throughout Europe. The Festival of Contemporary Music at LSU, established in 1940, is the oldest continually operating such festival at any major university in the country. The College of Music of Loyola University can trace its origins to 1932, when the earlier New Orleans Conservatory of Music and Dramatic Art was incorporated into the university. Students participating in its opera workshop have been very successful.

Special emphasis has developed in recent years on early music education within the university setting. The Music Academy of Louisiana State University offers musical education for preschool children. Loyola University College of Music is home to the Greater New Orleans Youth Orchestra, which boasts a selection of five orchestras for more than 250 young people from throughout Louisiana and Mississippi as well. The Bastien Piano Method, one of the most widely used piano pedagogy systems currently available internationally, is the result of efforts of Jane Smisor Bastien (Newcomb College) and James Bastien (Loyola University) to develop piano instruction appropriate for the youngest students.

Performing arts organizations have also pioneered music education outreach. In 1952, the New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony initiated what was at the time the largest educational effort of a major U.S. symphony. The resulting broadcast of a series of twelve concerts to every parish in the state reached 600,000 schoolchildren. In addition to outreach programs of symphony orchestras, opera, and ballet, Young Audiences, based in New Orleans, brings live music to more than 200,000 schoolchildren throughout Louisiana every year. The New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, a regional, preprofessional training center, offers secondary school students intensive instruction in dance, media arts, music, theatre, visual arts, and creative writing. Established in 1973, it was designed by a coalition of educators, artists, community activists, and business and civic leaders to address the needs of Louisiana’s young talent.

Sources for the Study of Louisiana Classical Music

The sources for the study of the classical musical tradition of Louisiana are as varied and rich as the music itself. A combination of civil records, church records, papers of individuals, and records of organizations, as well as material held by foreign repositories, provide scholars with a source that has yet to be exhausted. For example, succession records indicate that a contract was entered into between Rev. John B. Duffy, c.s.s.r., and New Orleans organ builder August Obstfelder on November 11, 1868, for construction of an organ for Notre Dame de Bon Secours Church on the corner of Jackson Avenue and Constance Street. Biographical data concerning Vicente Llorca, organist of the St. Louis Cathedral, are found in the chimney tax records for 1797. Church records are particularly useful. Frequently, internment records will contain information useful for musical researchers other than birth and death dates, spouses, and relatives. For example, it is possible to reconstruct the boy choir of the St. Louis Cathedral from the Spanish colonial period, as former members of the boy choir were identified as such in the internment record. Account books, church bulletins, and minute books of religious institutions are particularly valuable.

Numerous repositories hold records of performing arts organizations and individuals associated with the performing arts. Tulane University, for example, has the personal papers of Giuseppe Ferrata and Genevieve Pitot. The Historic New Orleans Collection has primarily records of presenting organizations, such as the New Orleans Opera Guild and the Community Concert Association of New Orleans. Louisiana State University has personal papers of composer Dino Constantinides and musician Henri Fourrier, among others. Such holdings are not limited to institutions in New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Rather, archives and manuscript collections of institutions of higher learning throughout Louisiana hold a wide variety of material documenting the classical music experience in the state.

Foreign repositories also hold relevant records. The Bibliotheque nationale de France’s music division has music of Edmond Dédé, while documentation on Ernest Guiraud is found in the same institution’s opera division located in the Opéra Garnier. The Archive of the Indies in Seville, Spain, contains documentation on the history of music in Louisiana during the Spanish colonial period. In a letter dated October 1, 1783, Estéban Miró (one of the Spanish governors of Louisiana) writes to José de Ezpeleta (governor of Cuba) requesting musicians for the regimental orchestra (Papeles precedentes de Cuba, legajo 1377). Another letter reveals the names of five French army deserters, all musicians, who arrived in New Orleans in 1785 (Papeles precedents de Cuba, legajo 2). These examples are indicative of the wealth of information waiting to be fully exploited by music historians of Louisiana.