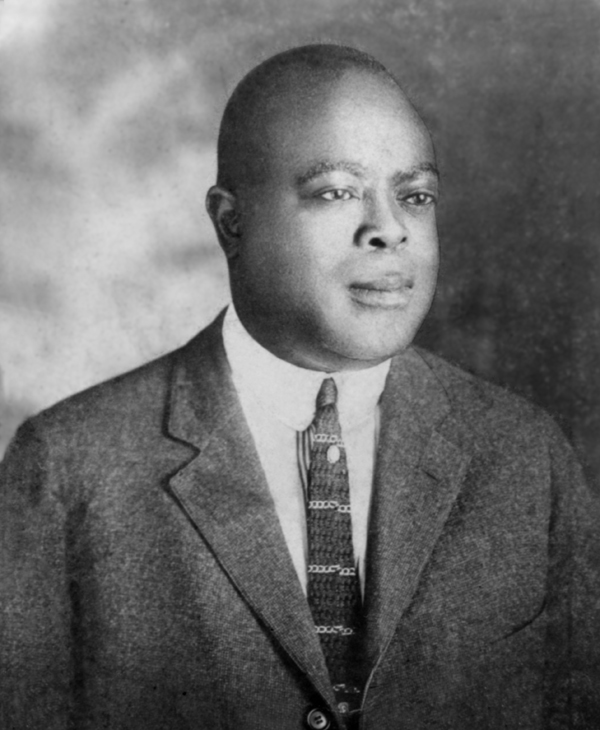

Joseph “King” Oliver

Pioneering jazz trumpet and cornet player and band leader "King"; Oliver played an instrumental role in popularizing jazz outside of New Orleans and was an important mentor in the life of Louis Armstrong.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Joseph "King" Oliver. Unidentified

A pioneering jazz trumpet and cornet player, bandleader Joseph “King” Oliver played an instrumental role in the popularization of jazz outside of New Orleans. Though born in Louisiana, Oliver spent much of his career in Chicago, where he established his legendary King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Initially, the band included Louis Armstrong, formerly Oliver’s student in New Orleans. Ironically, Armstrong’s success ultimately overshadowed his mentor’s reputation as a jazz pioneer. As both a teacher and a musician, however, Oliver played an important role in the early history of jazz.

Early Life and Influences

Joseph Nathan Oliver was born in Edgard, in St. John the Baptist Parish. Though the exact date has been in dispute, current evidence indicates that he was born on December 19, 1885. While Oliver was still young, his family moved to New Orleans. Orphaned in his early teens, he went to live with his half-sister, Victoria Davis. As a teenager and young adult, Oliver worked as a butler, but his passion was always music. He began playing as a child in a neighborhood brass band. As his musicianship progressed, Oliver performed in some of the most influential brass bands in turn-of-the-century New Orleans, including the Onward Brass Band, the Eagle Band (which included ex-members of Buddy Bolden’s group), and A. J. Piron’s Olympia Band.

Oliver’s musical skills placed him in a lineage of New Orleans trumpeters that included Buddy Bolden and Freddie Keppard. He developed a reputation as a strong player particularly adept at “freak” music, which involved using mutes to make the trumpet “talk” or imitate animals (creating, for example a “wah wah” sound). He was also well known for playing the blues in the “gut bucket” or “low down” style.

Oliver was a stern man, often quick to anger. But he also took a sincere interest in young musicians and always took the time to teach them proper technique. In was in this capacity that Oliver met Louis Armstrong. The two began a long musical relationship, with Oliver acting as a father figure to Armstrong. For the rest of his life, Armstrong spoke with deep admiration for Oliver. Oliver also taught Armstrong how to be a band leader, largely through example.

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band

In 1918 Oliver moved to Chicago to work in bassist William Manual “Bill” Johnson’s band. Oliver played with Johnson at the Royal Gardens Café. He performed with Lawrence Duhe at the Dreamland Café and in the White Sox Booster Band, which entertained audiences in the stands at baseball games. By 1920, Oliver was leading his own band at Dreamland. After performing briefly with Edward “Kid” Ory in California during 1921, he returned to Chicago to form his famous King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band in 1922. The band opened that year at Lincoln Gardens.

During the summer of 1922 Oliver sent for Armstrong to play second cornet. The band quickly gained a local reputation and made its first recordings on April 5 and 6, 1923, for Gennett Records. These recordings represented Oliver at his best and have attained legendary status in the history of jazz. The 1923 Creole Jazz Band included Oliver, Armstrong, Baby Dodds on drums, Honore Dutrey on trombone, Bill Johnson on bass, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, and Lillian Hardin on piano. Their first session produced nine tracks, including “Just Gone,” “Canal Street Blues,” “Weather Bird Rag,” “Snake Rag,” and “Dipper Mouth Blues.” Later that year, Johnny St. Cyr played banjo during a session that produced the lovely “Mabel’s Dream.” The hallmark of the Creole band sessions was the complex intertwining duets between Oliver and Armstrong, in which the student slowly surpassed the teacher. The band fell apart in late 1923, largely due to interpersonal problems among the members and financial issues. Armstrong’s increasing status led to some strain between the two, but Armstrong always deferred to Oliver on issues regarding the band. Lillian “Lil” Hardin, who had married Armstrong, pushed her husband to go to New York for better wages.

Later Career

Throughout the 1920s, Oliver frequently worked as a sideman on recording sessions for blues and popular singers. Some of these included Sara Martin, Victoria Spiver, Sippie Wallace, Texas Alexander, and the vaudeville duo Butterbeans and Susie. Oliver’s talent was particularly apparent when backing singers like Martin; his cornet performed a nearly perfect call-and-response pattern behind the singer. He also recorded duets with fellow New Orleanian Jelly Roll Morton.

In 1925 Oliver reorganized his band into a slightly larger group titled the Dixie Syncopators. This band attempted to conform to the growing demand for dance music rather than “hot” jazz. Oliver added a saxophone to his lineup and recorded popular tunes suggested by record executives. The recordings are uneven, though stellar solos and inspired segments can be found even in the poorer performances. Oliver struggled with the emerging big band sound and, in some ways, was eclipsed by Armstrong’s popularity. In 1927 he relocated to New York City. He took on more work as a sideman and appeared with various groups led by Clarence Williams. Oliver continued to front his own band, but his reputation was slowly slipping. He spent most of the 1930s touring the South and the Southwest.

By 1936 Oliver was headquartered in Savannah, Georgia. His health declined, and he experienced financial difficulties that began with the onset of the Great Depression. Though he remained optimistic about his future in music, by 1938 he was running a fruit stand and working as a janitor. He died on April 10, 1938, in Savannah and was buried in New York City.

Oliver’s reputation suffered over time, and jazz historians have often relegated him to the role of Armstrong’s mentor. Bad business decisions and difficulty adapting to changing tastes haunted him in later years. He was, however, a powerful player whose Creole Jazz Band recordings captured him at his best. He was also a hero to Louis Armstrong. In his autobiography Armstrong said, “It was my ambition to play as he did. I still think that if it had not been for Joe Oliver, Jazz would not be what it is today.”