Populism

In the late nineteenth century, Populist Party advocates railed against the prevailing system and urged cooperation among oppressed peoples to secure reform.

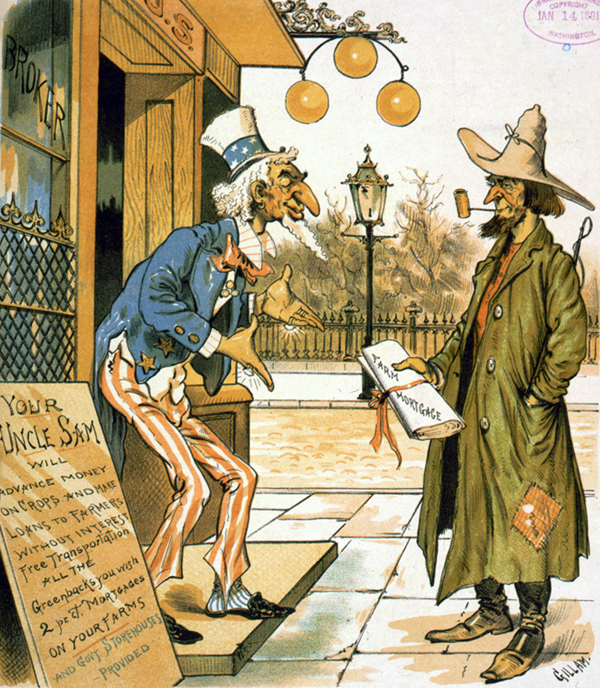

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

A color reproduction of a political cartoon entitled “The New Uncle Sam”, circa 1891.

In the late nineteenth century, Americans witnessed a period of rapid industrialization and a corresponding political realignment. Expanding transportation and communication networks transformed America from a rural agrarian-based society to a modern urban industrial society championed by the captains of big business. Increasing numbers of Americans came to enjoy modern conveniences ranging from electricity to paved roads, yet not all were pleased with the changing conditions. Before the turn of the century, a political reaction known as the Populist revolt would occur, pitting those who felt victimized by the new order against those who enjoyed its rewards.

Post-Civil War Poverty

In the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction, appalling poverty descended upon the South. Whole regions of the southern countryside had been devastated by war, and the federal government proved hostile to any legislation offering relief to the defeated rebels. The bankrupt southern states were forced to attempt to rebuild their shattered economies on the backs of people who had lost virtually everything. Southern farmers were also forced to pay taxes for all the years they had been out of the Union. As a result, scores of formerly proud and independent yeomen farmers were forced off their land. At the same time, emancipation not only wiped out a multibillion-dollar investment in a system built upon enslaved labor, it also injected huge numbers of freedmen into the labor pool, greatly exacerbating the economic chaos.

While formerly enslaved people embraced their freedom, they had generally been excluded from opportunities to build any type of wealth during slavery. They also had not been provided with the means necessary to sustain themselves—namely, land—after emancipation. Some freedmen were forced to steal livestock and crops to survive, a practice that pitted them at dangerous odds against desperate small farmers. Economic malaise and despair enveloped the south; in the eyes of many northerners, this was a just punishment for the defeated region.

In an effort to get people back to work and maintain the social and racial hierarchy of the Old South, many planters resorted to sharecropping. The sharecropping system allowed landless farmers, Black or white, to rent a parcel of land from a landowner in exchange for a share of the crop. Furnishing merchants likewise provided the sharecroppers with goods in exchange for a share of their crop. Since the sharecropper began with no resources, the merchant placed a lien on the crop, in exchange for food and other goods, which guaranteed the merchant’s share of the crop at harvest time. When sharecroppers went to settle up at the end of a planting season, they typically found that the cotton or tobacco they produced did not cover the year’s debts, and they were forced to sign on for another season, a process that ensured a never-ending cycle of debt and poverty.

Efforts to provide relief to suffering southern farmers were typically derailed by northern congressmen who “waved the bloody shirt,” reminding their colleagues that the same southern farmers now desperate for relief had previously cast their lot with the Confederacy. Making matters worse, southern state governments, as in Louisiana, were controlled by Bourbon Democrats, whose conservative fiscal policies demonstrated far more concern for their own financial well-being than the plight of farmers. Few in Washington or in any southern state government showed much realistic concern for the plight of Black Americans, who characteristically were assigned the bottom rung in the cycle of misery.

The Rise of the Populist Party

Aware that they would have to initiate any opportunities for relief themselves, farmers in eastern Texas and other scattered regions began to organize. Led by talented and energetic Charles Macune, the emerging Farmers’ Alliance, as it came to be known, focused on educating farmers who had lost the ability to control their own destiny in a world seemingly dominated by corporate greed. The Alliance taught farmers methods of improving productivity and encouraged crop diversification. Significantly, the Farmers’ Alliance also advocated a system of crop warehouses in which farmers could store their crops until prices rose. Members of the Alliance soon realized that education would not be enough to overcome the conditions that victimized them; a political movement would also be necessary to affect change.

Since Bourbon Democrats and the nationally dominant Republican Party often appeared as allies in exploitation, Alliance members concluded that it would take a new party to promote their interests. In states such as Louisiana, the very notion of supporting any party other than the Democrats—who were perceived by the white southern population as rescuing the south from the grips of carpetbaggers and scalawags—proved a very bitter pill to swallow. Despite such powerful concerns, by the late 1880s and early 1890s, utter desperation forced scores of Louisiana farmers, Black and white, to enlist in the new Populist Party.

Though some Farmers’ Alliance members such as Macune could not bring themselves to abandon the Democrats, tens of thousands did. The southern farmers found an ally among midwestern farmers, who also suffered from the institutional neglect of the federal government. In 1892 the Populist Party fielded its first presidential candidate, James B. Weaver. Though he failed to win, Weaver performed respectably. Increasing numbers of farmers flocked to the Populist banner as the farming crisis deepened in the early 1890s.

Central to the emerging Populist ideology was the subtreasury plan. Conceived by Macune, the subtreasury plan would empower the federal government to set up warehouse storage facilities and provide low-interest loans to farmers. The plan would free farmers from crop lien mortgages by allowing them to store crops until prices rose. It would also put more money into circulation. When Louisiana’s Democratic congressional delegation unanimously voted against the subtreasury plan, amid growing evidence of corruption courtesy of the Louisiana Lottery, the Populist Party officially came to life in Louisiana. Farmers in northern Louisiana proved particularly receptive to the nascent political movement. Homegrown leaders such as the Reverend Benjamin Brian, his son Hardy, and B. W. Bailey encouraged farmers to take a stand against injustice.

The Rise and Fall of the Populist Party

Aware that strength lay in numbers, Populist supporters reached out to the equally outraged Negro Farmers’ Alliance to advance their percentage at the polls. Across the state, Populist Party advocates hosted picnics and barbeques where orators railed against the prevailing system and urged cooperation among oppressed peoples to secure reform. Yet the sight of Black and white poor folk sharing a barbeque proved unimaginable to the state’s ruling elite, who increasingly regarded the Populists as a threat to their way of life.

In 1893 the nation descended into an economic depression, and the demands for an expanded money supply dramatically increased. In the 1894 congressional elections, Louisiana Populists made a determined effort to capture the Fourth and Fifth District congressional seats. Despite spirited campaigning and amid rampant allegations of fraud, the Populists were defeated, but not discouraged, in each race. Most observers concluded that if a fair election could occur, growing Populist strength in upstate Louisiana and the Florida Parishes would guarantee victory. Only in Acadiana, where the Democrats successfully painted the Populists as anti-Catholic Protestants, did the movement remain weak.

Over the next few years, worsening economic conditions and increasing disillusionment with the Democratic Party’s response produced growing numbers of Populists. As the election of 1896 approached, Louisiana Populists made overtures to southern Louisiana sugar planters, who frequently supported the Republicans and were also feeling the pinch of depression. Both groups relished the thought of unseating Democratic governor Murphy J. Foster—a shared purpose that would allow for a Populist-Republican fusion in the approaching gubernatorial campaign. To cement the alliance, the Fusion ticket endorsed St. Mary Parish sugar planter John N. Pharr, one of Louisiana’s wealthiest men.

If the fusion of Black and white farmers along with wealthy sugar planters could be maintained, the Populists seemed poised for victory. The Democrats, predictably, reacted with hysteria, alleging that the Populists represented racial equality and social upheaval. One Shreveport Democratic paper went so far as to declare, “it is the religious duty of Democrats to rob Populists and Republicans of their votes. Rob them! You bet! What are we here for?” Massive violence characterized election day 1896 across the state. When the Democratic-controlled state election commission completed the tally, it reported a narrow Foster victory. In many predominantly Black parishes the Populists received not a single vote, suggesting that the results had been tampered with or that Black men had been bulldozed into voting for the Democrats. Despite armed protests against the results, especially in north central Louisiana, Foster retained his position.

The election of 1896 broke the power of the Louisiana Populist movement. It also ushered in significant social change. In the next legislative session, the Democratic-controlled assembly passed sweeping electoral law changes that markedly contracted the electorate and concentrated power in the hands of the elite. Likewise, many former Populists who supported racial unity to achieve reform now believed that Black men were unreliable allies who should be removed from the rolls lest their votes be manipulated. It is perhaps not surprising that not long after the election a Louisiana court handed down a landmark decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which coined the term “separate but equal” and ushered in the era of legally enforced segregation—a dark legacy for a movement dedicated to improving the quality of life for Louisiana’s poor.