Battle of Liberty Place

The Battle of Liberty Place, September 14, 1874, effectively brought an end of Reconstruction policies in Louisiana.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

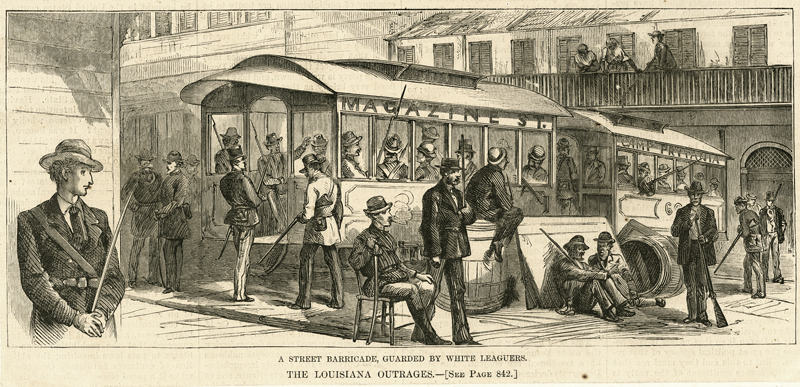

Reproduction of an illustration of A Street Barricaded, guarded by White Leaguers during the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans, 1874.

A pitched battle took place in the streets of New Orleans on September 14, 1874. In it, the Democratic-Conservative White League attacked the Republican Metropolitan Police for control of the city and to put an end to Reconstruction in Louisiana. Although the White League inflicted a stunning defeat on the Metropolitans and forcibly deposed Governor William Pitt Kellogg, its victory proved short-lived. President Ulysses S. Grant ordered the army to reinstate Kellogg three days later. Quickly dubbed “The Battle of Liberty Place” by the White League and its supporters, the clash not only marked a crucial turning point in the balance of power during Reconstruction in Louisiana, it served as a defining moment for a generation of elite, young white men in New Orleans.

Origins of the Conflict

The confrontation’s origins lay in Louisiana’s troubled gubernatorial election of 1872, which pitted Democratic-Conservative “Fusion” candidates John McEnery and Davidson Bradfute Penn against a Republican ticket headed by US senator William Pitt Kellogg and Caesar Carpentier Antoine. Widespread fraud made an accurate tally of votes impossible and, as a consequence, the election’s outcome hinged on control over the state’s returning board, the officials who validated election results. When competing partisan returning boards emerged, the Republicans moved to have the matter settled in federal court, where a judge decided in their favor. While Kellogg may have actually polled the greatest number of votes, his means of victory smacked of federal tyranny to white Louisianans who believed that President Grant had used the judiciary to sustain an unpopular Republican government in the South. That Kellogg’s political base was almost entirely black amplified this outrage and unified a previously divided white electorate.

Open resistance to Kellogg’s regime began in January 1873 when the Fusionists, ignoring the federal order declaring Republican victory, established a competing, shadow state government in the Odd Fellows Hall in New Orleans. The inability of this insurgent legislature to collect revenue, however, quickly undermined its effectiveness. By early March, in an effort to stave off Fusion’s impending demise, McEnery called upon a volunteer militia to attack the Metropolitan Police, which was under the control of the Republicans, and overthrow Kellogg’s government by force. Later dubbed the “Battle of the Cabildo” or “First Battle of Liberty Place,” this coup attempt failed. More unprepared mob than militia, the Fusionists were no match for the well-armed Metropolitans. Moreover, they had to avoid conflict with the US Army. As a consequence, after trading random shots with the Metropolitans, the Fusionist militia dispersed when ordered to do so by a federal officer. The next day, members of the Metropolitan Police broke up the Fusionist legislature. Yet the Republican victory was far from complete. Not only did the coup’s leaders go unpunished, they also learned important lessons that they would apply later in the Battle of Liberty Place.

The Emergence of the White League

As 1874 began, the popularity of President Grant and federal Reconstruction policy had reached an all-time low. Kellogg governed in Louisiana, but ongoing congressional debate in Washington over his legitimacy undermined his effectiveness. At the same time, Kellogg’s Republicans selectively championed the enforcement of civil rights legislation, a move that may have energized black electoral support but also cost the party many of its remaining white allies because such legislation fed white fears of “Negro domination.” These conditions led Democratic-Conservatives to believe that a second, better-planned effort to violently overthrow Kellogg would meet with tactical success and national approval. Meanwhile, a potent new political organization called the White League emerged in Louisiana’s rural parishes. Organized along paramilitary lines and devoted to white political rule, the League methodically assembled a force capable of defeating both the state militia and Metropolitan Police.

Using a sophisticated campaign of propaganda that targeted the emotional and financial anxieties of the city’s residents, the White League first called for volunteers in New Orleans on July 5, 1874. That call quickly raised 1,500 men under the capable leadership of Frederick Nash Ogden, who had led the failed Cabildo raid in March 1873. Organized political violence was not new to New Orleans or to Ogden. Yet the White League represented political militarism on a scale that had never before been seen in the city nor has been seen since. Throughout July and August, dozens of companies of White League volunteers drilled in private club rooms and ward meeting halls across the city, while the League’s leadership acquired scores of obsolete Civil War arms that had recently been sold off by the army and were now available cheaply from merchants in the North.

Past chroniclers have noted the enormous influence of the city’s exclusive men’s clubs such as the Boston and Pickwick in the formation of the League, but the organization included white men from all walks of life. From a political standpoint, the White League in New Orleans was a coalition, its members united by the promise of eliminating the cloud of defeat that had hung over their generation since the end of the Civil War. Like Ogden, the vast majority of the leaders of the White League were veterans who had not yet turned forty years of age. About a third of the rank and file, however, were men in their early twenties who had been too young to fight in the Civil War and who had come of age during Reconstruction. For them, the League represented a second chance at a missed opportunity.

Setting the Stage for Conflict

Throughout the summer of 1874, the Democratic-Conservatives executed a skillful campaign of political propaganda and oratory, often accompanied by torch-lit processions of the White League. In New Orleans, the League carefully manipulated the Metropolitan Police into arresting citizens for carrying or transporting arms and exploited such incidents in the press in order to underscore what the League characterized as Republican tyranny. When a White League spy told Metropolitan Police Superintendent Algernon Sydney Badger that the League planned to receive a large shipment of arms at the levee on September 14, 1874, it set the stage for open confrontation. Nor would the federal army be able to intervene in the pending clash. Fearing an outbreak of yellow fever, all but a skeleton garrison of troops had been sent to an encampment in northern Mississippi.

D. B. Penn, the Fusionist lieutenant governor, had assumed responsibility for the success or failure of the White League’s efforts. Remembering the disastrous Cabildo raid, he would not endorse any action unless satisfied that it enjoyed broad popular support in the city. Therefore, on Sunday evening, September 13, the League blanketed New Orleans with handbills announcing a “meeting of the people” around the Clay Statue that then stood at the intersection of Royal and Canal Streets and St. Charles Avenue. Perhaps five thousand people attended on Monday morning to hear speeches calling for the resignation of Governor Kellogg. A delegation from the meeting called on the governor to request the same. Kellogg refused to abdicate, but sensed the coming conflict and fled with his staff to the sanctuary of the US Custom House on Canal Street. Before leaving, he placed Superintendent Badger and militia general and former Confederate general James Longstreet in charge of defending his government. Meanwhile, the White League severed all telegraph lines leading out of the city.

The Battle on Canal Street

General Longstreet had once been in command of a state militia that included many former Confederates. With the ascent of Kellogg, however, only his black regiments remained in uniform. Longstreet, unsure of their ability to meet the coming foe, kept them as a reserve guard at the statehouse, which occupied the old St. Louis Hotel in the French Quarter. The Metropolitan Police, a well-trained and superbly armed force, would alone meet the White League in a defensive position on Canal Street. The Metropolitans were an integrated force, though only about 15 percent were men of color. Superintendent Badger, their leader, was a brave and highly decorated soldier. He posted his command near the present location of Harrah’s Casino, where the Metropolitans waited with cannon and newly acquired Gatling guns.

Leading an unprepared mob into battle was a mistake that Ogden would not make twice. While the mass meeting took place on Canal Street, companies of the White League descended upon Eagle Hall at the corner of Prytania and Urania streets and assembled for their march downtown. At Poydras Street, the Leaguers erected defensive barricades and proceeded toward Canal Street through the present-day Central Business District. In disciplined columns, with snipers positioned in the buildings along Canal Street, the White League met the Metropolitans along Canal Street in a line extending from the levee to the custom house.

Intense fighting quickly erupted between the League and Metropolitans, while bystanders numbering in the thousands looked on. Within fifteen minutes, the battle had turned into a rout, with Metropolitans fleeing frantically toward the sanctuary of the Custom House or to their homes. The battle differed considerably from other episodes of Reconstruction-era violence in that it was an action instead of a riot or massacre. Among the dead were sixteen White Leaguers, thirteen Metropolitans, and six bystanders. Scores were injured, some seriously, including Badger, who was shot four times trying to rally his men. Admiring his bravery, Badger’s enemies carried him to the hospital under special guard.

Within hours, the White League controlled the entire city. The black state militia filtered out of the surrounded statehouse and were forcibly disarmed and disbanded by the League. Meanwhile, Kellogg and the remnants of his government remained safe in the Custom House. The White League quickly set about establishing the trappings of government, including an inauguration of McEnery and Penn. Aware that much would hinge upon public opinion, they also took care to avoid outrages like the Colfax Massacre, which had happened earlier in the year, and they were mostly successful in this endeavor. Around the nation, some newspapers decried the actions of the White League, but a great many applauded Kellogg’s overthrow. President Grant, however, was incensed and ordered the army to force the League to surrender. Not wishing conflict with the federal government, three days after the League’s victory, it handed control of the city to federal troops, who in turn gave control back to Kellogg.

Aftermath and Legacy

Despite failing to achieve its ultimate objective of regime change, the White League’s victory in the Battle of Liberty Place resulted in a key power shift in the state. The Metropolitan Police were irrevocably broken by the conflict, and the black state militia ceased to exist. Only the federal army kept Kellogg in power, and many of its soldiers were predisposed against the Republicans. Kellogg’s control in most of rural Louisiana had ceased entirely. Meanwhile, the White League not only went unpunished for its rebellion, it remained armed and continued to grow in New Orleans and elsewhere. As politicians negotiated the Compromise of 1877 in Washington, the White League under Ogden took control of the city, essentially ending Reconstruction in Louisiana and ensuring the victory of Francis T. Nicholls as governor in the election of 1876. After “redemption,” the White League became the official state militia.

The battle also proved crucial for the generation of New Orleanians who took part. To say that one had fought at the Battle of Liberty Place conferred a sort of distinction that few other accomplishments could equal. Heavy participation by Mardi Gras royalty in the League renewed their claim to civic leadership. In 1891, the city installed the Liberty Monument at the foot of Canal Street to commemorate the White League dead, and annual wreath-laying ceremonies took place there until the start of World War I. In subsequent years, the monument became an increasingly powerful political symbol for white supremacy and took on new meaning as later generations tried to find metaphors for their own deeds in the military exploits of the White League.

By the 1980s the Liberty Monument, along with all of the white supremacist language that had been added to it in the 1930s, had become a contentious issue. Renovations to the riverfront, along with political pressure, led to its temporary removal and an ensuing debate as to whether or not it should return to public view. Ultimately, the obelisk returned to an obscure corner of Iberville Street near the entrance to the Canal Place parking deck, a compromise location. The monument was removed by order of the City of New Orleans on April 24, 2017.