Woman Suffrage

The movement for women's rights in Louisiana started with benevolence work in church groups and progressed to the campaign for woman suffrage.

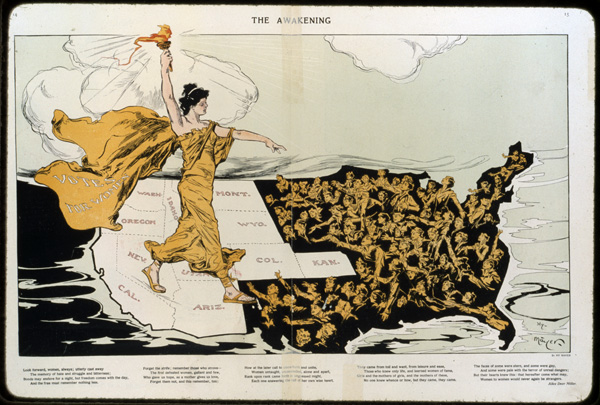

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The Awakening. Mayer, Henry (artist)

Writing in 1970, historian Anne Firor Scott identified the process by which Southern women progressed along a continuum of social and political activism. First came benevolence work in church groups, tract societies, and prayer meetings. From this, some women went on to membership in voluntary associations that attempted to achieve reforms of various societal ills, such as child labor, unsafe working conditions, cruelty to animals, and a host of others. The disappointing discovery that women’s indirect influence was insufficient to bring the changes they sought led many (but certainly not all) of them to become converts to the campaign for woman suffrage, which Scott saw as the ultimate stage of the continuum.

The movement for women’s rights had gained steam in the Northern states decades before Southern women showed much interest. Indeed, the fact that the campaign for woman suffrage was an offshoot of the antislavery movement tainted it in the minds of many southerners. When the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments extended the vote to African American men but ignored women, suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony protested vehemently, noting accurately the staunch support the women’s rights movement had given abolitionism. Thus, when national women’s leaders united in 1890 (a full generation after the Civil War) to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), they found resistence in the South, where public opinion tended to dismiss woman suffrage as an alien idea touted by Yankee abolitionists. In the 1890s, Southern state legislatures were completing the process of disenfranchising black men via a host of creative subterfuges such as the poll tax, the literacy test, complicated residency requirements, and cumbersome registration processes. They spurned any constitutional change that would again insert the federal government into the prickly area of voter qualifications. Additionally, the well-known Southern preference for demure, submissive women worked to dampen the popularity of woman suffrage in the South.

A popular second-wave feminist expression, “hearing the click,” refers to the moment at which a woman realizes that she is suffering the effects of patriarchal, sexist bias. New Orleanian Caroline Merrick (1825–1908) related an anecdote that neatly encapsulates how one group of white Louisiana women “heard the click” in the late nineteenth century. A German woman, dying at St. Anna’s Asylum for destitute women and children, desired to leave her life’s savings of one thousand dollars to that institution, and, on her deathbed, made a will to that effect. Much to their chagrin, the women on St. Anna’s board of governors who witnessed the document later learned that the will was invalid; as women, they had no legal standing to witness a will. Wrote Merrick, “The bequest went to the state, and the women went to thinking and agitating.”

Organizing in Louisiana

Merrick became an early convert to the cause of woman suffrage and founded the Portia Club in 1892 as an auxiliary of NAWSA. In 1896, New Orleanian Kate Gordon (1861–1932), having heard a Colorado suffragist speak at her Unitarian church, founded the Era Club, whose name stood for “Equal Rights for All.” In 1898, representatives of both clubs appeared before the Louisiana constitutional convention’s suffrage committee to urge the adoption of a woman suffrage amendment. Although unsuccessful, the women of Louisiana did win a partial victory when delegates wrote a provision giving all tax-paying women the right to vote on questions of taxation.

A year later, New Orleans voters faced a bond issue to fund creation of an adequate sewerage and drainage system for the flood-prone city. Gordon spearheaded the effort to mobilize eligible women for the measure’s passage and organized parlor meetings to educate them on the merits of the issue. However, she encountered reluctance on the part of many to go to the polls at all; custom had conditioned most women to regard politics as utterly inappropriate for them, and most men did little to disabuse them of that view. Perhaps anticipating such timidity, the lawmakers had provided that women might vote by proxy, so Gordon accordingly collected some three hundred proxies, which she then voted on election day. The measure passed, and the local press saluted women for the role they played in securing a tax increase to rescue the city from its poor drainage and primitive sewerage disposal. Particular praise went to Gordon, who from this point forward would dominate, and complicate, the woman suffrage movement in Louisiana.

The much-publicized turn of events in the New Orleans election impressed leaders of NAWSA, leading their president to remark, “If ever there is another vacancy on the national board, it will go to the little woman down in the conservative old state of Louisiana.” Accordingly, in 1901 NAWSA chose Kate Gordon as correspondence secretary. Departing for New York to take up her duties, Gordon gave an interview that revealed how inextricably her thinking on woman suffrage was mixed with her thinking on race. Like most conservative Southern Democrats, Gordon felt that black voters were a source of corruption and saw black disenfranchisement as a progressive reform. Anne Pleasant, wife of Louisiana Governor Ruffin Pleasant, spoke for many when she worried that “the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment would embolden the negro [sic] man and the negro woman to give us even greater trouble than they are doing now.” Recognizing that many Southerners feared that enfranchising women could lead to a resurgence of the black vote by bringing federal intrusion into a state’s affairs, Gordon argued instead that enfranchising women, if via a state amendment, would ensure white supremacy: “[G]iving the right of the ballot to the educated, intelligent white women of the South…will eliminate the question of the negro vote in politics….The South…will trust its women, and thus placing in their hands the balance of power.” Gordon predicted that “the negro as a disturbing element in politics will disappear….”

Southern African American women who backed woman suffrage tended to maintain a low profile, convinced that their support, should it become known, could only hurt the cause in the South. Suffragists at the national organization were uncomfortable with Gordon’s rabid racism, which found frequent and explicit expression in her speeches and writings, but, for a time, they tended to presume that she spoke for Southerners.

Seeing that NAWSA increasingly directed its energies toward a federal amendment, Gordon eventually grew disenchanted with that group and in 1913 formed the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference (SSWSC), dedicated to state-controlled suffrage. This body was not representative of all Southern suffragists, nor even of all Louisiana suffragists, most of whom were not as ideologically inflexible as Gordon. Most simply wanted the ballot and cared not for distinctions of state versus federal action. Indeed, by 1910 the prospects for a federal amendment had grown. Moderate suffragists Sake Meehan of New Orleans and Lydia Holmes of Baton Rouge spurned the narrow approach of SSWSC and the heavy-handed leadership of Kate Gordon, and in 1913 they formed a separate group, the Woman Suffrage Party of Louisiana. The WSP affiliated with NAWSA, worked energetically for passage of the federal amendment, denounced the racist, states’ rights approach of Gordon and her allies, and feuded with SSWSC.

Internal Dissent

Kate Gordon was, by all accounts, an exciting public speaker whose keen and outspoken intelligence was enlivened by touches of humor, but she was also an inflexible leader who feared black enfranchisement and viewed any failure to fall in line with her positions as a form of treachery. In her suffrage leadership, she generated tensions, indulged in personality conflicts, and was prone to petty jealousies. The upstart WSP affronted her as much by its challenge to her leadership as by its embrace of a federal amendment strategy. Even the local press got wind of the schism and scolded obliquely, noting “the suffragist everywhere should cease to regard herself as the petty dictator of a personal clique, and suffrage as a fad to be pursued under her personal supervision.” Despite this advice, SSWSC and WSP never managed to work cooperatively together. This fact, coupled with the existence of a strong anti-suffrage faction of men and women, meant a three-cornered struggle that ultimately doomed woman suffrage to failure.

In 1916, NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt ruled that NAWSA affiliates should not undertake campaigns for a state suffrage measure in states where victory seemed less than certain, fearing that a defeat would diminish the growing momentum of the suffrage cause nationally. In 1918, the Nineteenth Amendment passed the US House of Representatives, but later that year Southern Democrats blocked the measure in the Senate. The defeat left Gordon jubilant, for she believed that the way was now clear for state suffrage measures to succeed in the South as a clear alternative to the dreaded federal mandate. Governor Ruffin Pleasant called for passage of a state suffrage amendment and requested Kate Gordon to frame a memorial to the lawmakers urging them to act. Confident of success, Gordon told NAWSA to send no money, no literature, and no personnel to Louisiana. Warning NAWSA to stay out of the campaign entirely. she insisted that southern women must do the work of persuading Louisiana men and indicated that her theme would be “loyalty to the Democratic Party [which had endorsed suffrage via state action in its 1916 platform] and resistance to federal intervention in the state’s right to regulate the franchise.”

Agents of Gordon’s SSWSC and of the more moderate WSP lobbied hard for the measure, though characteristically working independently rather than together. The bill passed the state senate, 31 to 4, and the state house, 80 to 21, in June 1918, and faced the voters of Louisiana that November. Influential antisuffragists then organized the Men’s Anti-Woman Suffrage League, with State Senator J.R. Domengeaux, a manufacturer from Lafayette, as president. Despite the backing of both of Louisiana’s US senators, all congressmen but one, the governor, and the state’s urban daily newspapers, the November referendum went down to defeat by 3,500 votes, a crushing blow to Gordon and a severe shock to all suffragists. The political machine-controlled vote in New Orleans went heavily against the measure, providing the margin of defeat.

Despite this momentary setback in Louisiana, victory was near on the federal, or Susan B. Anthony, amendment. In June 1919, the U.S. Senate again took up the Nineteenth Amendment and passed it by a vote of 56 to 25. (Louisiana’s senators split on the vote, with Edward Gay opposing and Joseph Ransdell supporting it.) The federal amendment required ratification by thirty-six states in order to become law, and, in fairly short order, thirty-five states approved the measure. States’ rights suffragist Gordon enlisted in the battle against it. She traveled to Jackson, Mississippi, to speak against ratification by that state’s legislature and then worked strenuously in her home state to see it defeated. Ironically, she expressed regret that she was classed with anti-suffragists in the struggle, because she insisted that she fervently wanted woman suffrage, but not as a gift from Uncle Sam. However, to most people, her position was a distinction without a difference.

The Louisiana legislature considered both a state amendment and the federal measure in 1919. The house passed the state measure handily but the senate killed it, dashing the hopes of states’ rights suffragists. Then both houses rejected the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. Pressure from the sugar producers, the liquor lobby, and the state’s manufacturers played a role in the outcome, as did the traditional code of male chivalry, which honored women so much that it protected their special purity by refusing to enfranchise them. Nor can New Orleans Mayor Martin Behrman’s control over a sizable bloc of legislators be discounted. But the ceaseless squabbling among the state’s suffragists themselves counted heavily in explaining the failure of Louisiana to accept woman suffrage.

In August 1920, Gordon traveled to Tennessee to attempt to stave off ratification there. When that state became the thirty-sixth to approve the Nineteenth Amendment, making it law, her sister Jean issued a strangely sad and bitter statement to the press: “Tennessee has disgraced the South. I can only say that I am glad it is not Louisiana which has brought this ignominy upon us. I am in the position of a woman who has worked for suffrage all her life, and now that it has come about I do not want it.”

“The woman suffrage movement in the South should be seen as two movements,” wrote historian Elna Green, “one supporting federal legislation and the other insisting on state action, which created a complex three-way contest over the enfranchisement of women. Louisiana presents the clearest example of the dynamics of this three-sided contest….”

Given this turbulent and often confusing prelude to the enfranchisement of women in Louisiana, it is not surprising that after 1920 many Louisiana women approached the ballot with uncertainty or turned away altogether. Louisiana lawmakers did not make their peace with the reality of the woman suffrage amendment until 1970, when at last they ratified the measure in a symbolic acceptance of the fifty-year reality of votes for women.