Sound Advice

Henry Roeland Byrd Fesses Up

A feature-length interview with Professor Longhair is released on DVD alongside the 1982 documentary "Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together"

Published: June 4, 2018

Last Updated: January 15, 2019

by Michael P. Smith.

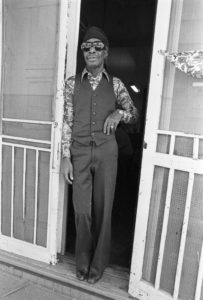

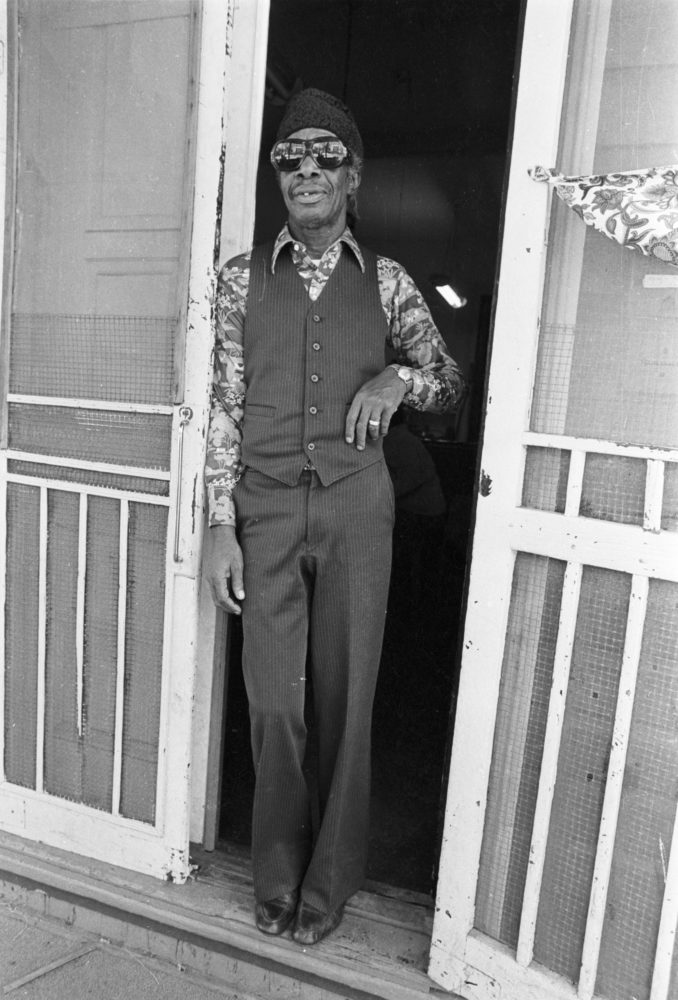

Professor Longhair at his home in 1979. Photo courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Byrd’s unique approach was based in large part on the Afro-Caribbean three-count tresillo pattern that is most often associated today with such song forms as the rumba and the mambo. In Louisiana it is also heard in zydeco, and, in New Orleans, in a variety of second-line beats used in R&B and jazz. These beats have infused a broad spectrum of Crescent City music since the early eighteenth century, underscoring the status of New Orleans and South Louisiana as the northern frontier of Caribbean culture—especially in terms of connections with Cuba and Haiti. Many prominent and influential pianists—including Louis Moreau Gottschalk and Jelly Roll Morton—have delved into such tempos and reworked them in various ways, imprinting the tresillo feel ever deeper into New Orleans’ collective consciousness.

To these various syncopated patterns Professor Longhair added the time-honored folk tradition known as “jumping time.” This means that, although still adhering to a song’s established chord progression, Byrd would make chord changes at random, with no thought that successive verses had to be the same length. With this orientation Byrd created distinctively original and complex bass lines and chord patterns, along with intricate right-hand riffs that morphed into even more ornate solos. As inspiration dictated, Byrd played suspenseful vamps and then released the pent-up tension by tearing into joyous bursts of notes that raced up and down the keyboard in startling displays of dynamics, harmonics, and unlikely intervals.

As Mac Rebennack, better known as Dr. John, stated in his 1994 autobiography Under A Hoodoo Moon: The Life of the Night Tripper, “All New Orleans pianists today owe Fess. He was the guru, godfather, and spiritual root doctor of all that came after him.” Those who came along soon after Fess included Rebennack, Allen Toussaint, Art Neville, James Booker, and Huey “Piano” Smith. His legacy lives on today thanks to pianists including Marcia Ball, Davell Crawford, Tom McDermott, Jon Cleary, Josh Paxton, Tom Worrell, Henry Butler, and Joe Krown.

Byrd’s idiosyncrasies also imbued his vocal phrasing. He loved to stretch single-syllable words into elaborate strings of notes, thus using his voice as an improvisatory instrument. He often eschewed actual words for extended scat singing, as heard, for example, on his signature song “Tipitina”: “Tra la-la la-la-la, tra la-la la lay . . . Tipitina oola malla walla dalla… tra la-la la lay.”

Byrd began recording in 1949, cutting many fine, popular songs for various labels, both local and national. But commercial success largely eluded him. Some two decades later, many people on the New Orleans music scene thought that Professor Longhair had either left town or died. In truth Byrd had abandoned music in disgust and was working as a janitor. But in the early ‘70s Quint Davis, now the producer and director of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, dramatically revived Byrd’s career. When the nightclub Tipitina’s opened in New Orleans in 1977, its name underscored Professor Longhair’s emergence as the leading hero of a cultural resurgence that was energizing the city. (This era also saw parallel resurgences in Cajun music and zydeco, as manifested, in 1974, in the founding of the event now known as Festivals Acadiens et Créoles, which still flourishes in Lafayette.)

“All New Orleans pianists today owe Fess. He was the guru, godfather, and spiritual root doctor of all that came after him.”

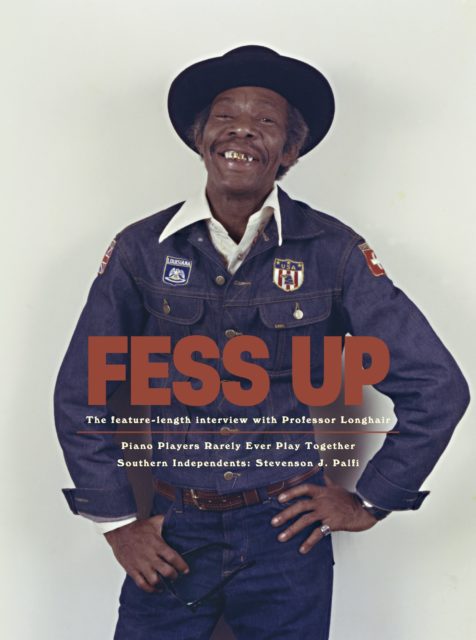

Besides “Tipitina,” Professor Longhair is best known for classics including “Bald Head,” “In The Night,” “Her Mind Is Gone,” and “Ball The Wall,” as well as the perennial Carnival-season anthems as “Big Chief” and “Mardi Gras In New Orleans” (later re-recorded and released as “Go to the Mardi Gras”). While these latter two songs are anchored by tresillo rhythms, Byrd also cited the Jamaican sound of calypso—which is not typically associated with New Orleans—as a major source of his rhythmic inspiration. This is one of many such revelations in a fascinating ninety-four-minute interview with Byrd conducted in 1980 that was filmed by the late documentarian Stevenson Palfi. It was just released on DVD this April under the title Fess Up (Palfi Films, fessup.palfifilms.com) along with a DVD reissue of Palfi’s acclaimed 1982 documentary Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together. The two-DVD package also includes brief excerpts from a profile of Palfi that was filmed for a series entitled Southern Independents.

The interview reveals Professor Longhair as a man of keen insight and resourcefulness. For example, he explains that the origins of his unique style were based in part on poverty that precluded the purchasing of new instruments: “Werlein’s [a music store in business from the mid-1850s until 2003] . . . used to take old pianos . . . they’d set them out on the street . . . we’d drag them in the house or in the alleys and different places. And I learned how to fix pianos this way . . . get hammers off of one piano and put them in the other . . . If it wouldn’t work, I’d tie a chord string or thread in it and bring it up to the next notch and tie it in where the action would work . . . This is why I learned to start crossing the piano. If a key didn’t play, it didn’t matter to me, I’d find some other key to substitute . . . this is all I would have to work with.” There are many other such revelatory gems within the interview, and Byrd also plays and sings excerpts from many of his best-known songs to illustrate the points that arise.

The other half of this package, Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together, is a fascinating profile of Byrd and two other New Orleans pianists: Isidore “Tuts” Washington (1907–1984), Byrd’s elder and a mentor of sorts, and Allen Toussaint (1938–2015), Byrd’s avid younger admirer. Although Washington’s name does not elicit great recognition today, he was a highly respected pianist whose eclectic work embraced classic early jazz and ragtime, blues and boogie-woogie, R&B session work with the big-voiced New Orleans singer Smiley Lewis, and sentimental standards and light classical pieces played from sheet music. Toussaint was a true renaissance man of both New Orleans R&B and contemporary popular music in general—a pianist, songwriter, arranger, producer, back-up singer, and, years after Byrd’s death, a successful solo artist. In the film Toussaint recalls that “throughout my childhood, whenever there was a Fess record nearby, don’t care how far it was, I would find it and learn it. And I just idolized him.”

Piano Players primarily intersperses interviews and solo performances by these three as they rehearse for a planned keyboard-trio concert at Tipitina’s. (The film also includes excerpts of live television performances from the ’70s, for which Fess’ accompanists included The Meters and Dr. John.) Byrd, Washington, and Toussaint all express some doubt that they can perform together, as if such collaborations were unprecedented—hence the film’s title. (Strong precedents for this trio format did exist, however. In the late 1930s, for example, the prominent and influential boogie-woogie artists Pete Johnson, Albert Ammons, and Meade Lux Lewis performed together, each on his own piano, at prestigious venues in New York City. They recorded in this configuration, too.) Despite such concerns the rehearsals show that Byrd, Washington, and Toussaint could play together quite effectively, meshing their distinct personal styles and showing each other great respect and affection. Watching them interact, and hearing their individual comments about the project, is a delight.

Sadly, before the concert took place, and just before the release of his long-awaited comeback album Crawfish Fiesta (Alligator) was released, Byrd died suddenly. Instead of documenting the concert, therefore, Palfi filmed Byrd’s funeral. One highlight of this deeply moving event found Allen Toussaint playing a poignant minor-key adaptation of “Big Chief’ to which he added new lyrics: “Thank you, Lord, for this very special man, thank you for letting me be around to see one as great as he.”

Since his passing Professor Longhair’s accolades include a 1987 Grammy award for a reissue album and induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992. A cast-iron bust of Professor Longhair stands in the entrance of Tipitina’s, symbolizing his seminal stature in New Orleans music and culture. But the joyous Fess Up is the ultimate posthumous testament to the genius of Henry Roeland Byrd. It stands as the most important historic reissue of New Orleans music and interviews to appear since the 2005 release of Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings, made by Alan Lomax in 1938.

Fess Up is presented by Polly Waring, the original associate producer of Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together, with contributions from Blaine Dunlap, Aimée Toledano, and Tim Watson. The DVD package includes a thirty-eight-page booklet with numerous photos along with informative commentary by Bruce Raeburn, Johnny Harper, and Michael Oliver-Goodwin.

—

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist, and producer and is the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his most recent book, Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012. In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contribution to the Humanities.