The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana: Preserving the Past to Make Way for the Future

An interview with Bertney and Linda Langley

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

All photos by Brian Pavlich

Tribal member Kassie Battise Dawsey holds a framed double-portrait photograph of Jeff and Sissy Abbey brought to the archives by one of their descendants. Tribal archivists encourage community members to bring in historic objects and photographs, sharing their knowledge and stories for future generations.

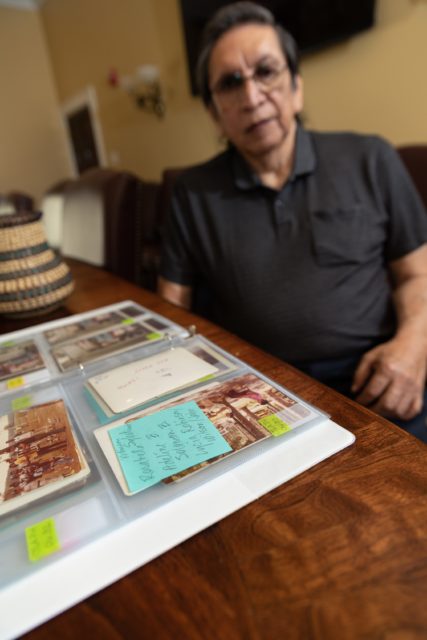

Bertney and Linda Langley are a husband-and-wife team who have dedicated themselves to the preservation of the Coushattas’ culture, history, and language. Bertney is a tribal member and Coushatta traditional cultural advisor; Linda, a non-tribal member who is an anthropology professor retired from McNeese State University, serves as the tribe’s historic preservation officer. Together with the tribal council , committed tribal members, and their allies, the Langleys have built the Coushatta Tribal Archives to house an inventory of records, photographs, and physical artifacts, including both items held by the tribe and its members and those held by research institutions or archives. The archaeological findings, oral histories, artifacts, photographs, and various other materials now in the Coushatta Tribal Archives record centuries of Coushatta history and heritage.

The Coushattas first encountered Spanish explorers in the Tennessee River Valley in the mid-sixteenth century and relocated several times to avoid European encroachment. By the end of the eighteenth century, the majority of Coushattas had established villages in Louisiana and Texas. Although some families settled in Oklahoma and Texas, by the 1880s approximately three hundred Coushattas had found permanent residence along southwest Louisiana’s Bayou Blue in Allen Parish. In the 1930s, the tribe received funding for education and healthcare from the federal Office of Indian Affairs. This funding was short-lived, however, and in 1953 these resources were abruptly withheld without formal action to terminate the tribe. The tribe had to overcome several hurdles before services were reinstated, including lobbying the Louisiana legislature to pass the state’s first tribal recognition resolution (1972), and convincing the US Department of the Interior to formally acknowledge the Coushatta tribe through administrative channels (1973).

Today, the Coushatta tribe thrives as a sovereign nation, with vast landholdings, varied economic enterprises, and several administrative departments. The Coushatta Tribal Archives is being developed not only to preserve the culture and history of the tribe’s 960 members but also to increase the public’s awareness of their contributions to Louisiana history. In addition, the archive’s founders intend to ensure that the Coushatta have access to the recorded information about their tribe and their ancestors. Previous generations of researchers often treated indigenous groups as subjects of study but failed to give tribes access to the materials produced about their culture and with their cooperation. The new archive helps ensure that the Coushatta will be the leading voices in discussions about their past, present, and future.

At what point did the tribe begin collecting historical materials?

Bertney: The older people often kept records, because they were concerned that we aren’t going to have a written history of this tribe eventually, if we don’t start to keep written records and make copies for everybody around here. I started around 1977 when I first came to work for my tribe, and it was because of some of the interactions we had with Bureau of Indian Affairs officials that I thought, “Let’s keep some of these records for later.” I just started this process and kept collecting and putting things in boxes.

Linda: When I first met Bertney in the 1980s, he had already been collecting things. He had what we called “Bertney’s boxes”—three large storage boxes of articles, old reports, and things that he just thought were important to keep. He kept flyers, correspondence, and photographs. Others in the tribe did the same thing, storing and collecting things over the years. They just didn’t have a central repository or place to bring them. Later, when we created the tribal archive, we attributed specific collections to the people who brought them in.

A Coushatta river cane storage basket made around 1930 and traded at the Tupper General Store is now on permanent loan to the Coushatta Tribal Archives from the Tupper Museum in Jennings.

What are the origins behind the founding of the Coushatta Tribal Archives?

Bertney: We started off trying to keep our language going because we were afraid of losing it. Linda started doing some research and was able to get funding in 2006 to start trying to teach and write the language. From there, it evolved to also include cultural and historical preservation.

Linda: We realized that it’s all connected. You cannot just get people together to tell you a bunch of words. For example, we started by trying to capture words about basketry, but nobody was making cane baskets at that time. The people realized that they had to get started making them again to be able to talk about the process. The same went for dancing or stick ball. These efforts even applied to the old way of making pottery. Documenting these traditions naturally led to revitalizing them. Even though we started with language, it evolved into the preserving of a more holistic heritage because language doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Bertney: The elders had a part in this whole thing, because we would ask questions like “how did you all keep the language going?” They said, “Well, we used to get together and sew baskets and help each other.” That was how they kept the language going, so that is what we wanted to start again. We had a kickoff meeting for the community and about three hundred people showed up.

Linda: At the first meeting I had this academic idea of how things should go. I had sign-up sheets on each table for different subjects. In my mind, this was all separate. However, people signed up for everything because I didn’t realize that in their minds it’s all connected. So, instead of separate committees, we ended up forming one committee that we call the language committee, although it addresses everything. If we have a history question, it goes to this committee too.

Bertney: Thirty volunteers agreed to serve on this committee.

Does the committee often come to a consensus?

Bertney: Yes.

Linda: Often, two siblings will sit and discuss how to say something. Then members of another family will sit and discuss on their own. We’ve gradually evolved the process. We’ll put somebody from a younger generation with each little cluster so they can talk it out. Then we’ll holler to the group that “they’re saying it this way,” and the bigger group will say “yeah, that sounds right.” When we don’t have consensus, we tag it both ways. People from other tribes are amazed by the Coushatta process.

Koasati (Coushatta) language preservation and revitalization projects are directly tied to the work of the archives. These pictures, grouped under the prompt “What do you do every day?” help tribal teachers teach Koasati to young and old alike.

Did these efforts evolve to include developing a tribal archive?

Linda: Yes, at the direction of the tribal members. There was so much that they wanted their kids to know. They didn’t want their history to be stuck in a dusty archive or lost in obscurity. It was to be brought home so they could use it for what they wanted. What really triggered it for me was when, in the late 1980s, a group of about six elders came up to me and said, “We realize that we made a mistake. All these years people have come here, and they made recordings and wrote books, but they got so much wrong. And we laughed about it and thought, ‘Let them think whatever they want to think.’ But we made a mistake because now we’re starting to lose it, and we need it to come back. We need to fix it.” And they asked me, “Can you get everything back and fix all the mistakes that others made about our history and language?” From that day, it has become an enormous mission in my life to help. I told them that I would do the best I could. Even though the tribe didn’t hire a trained archivist until 2018, the collecting and archiving process started much earlier.

Bertney: We had young people that we recruited.

Linda: Bertney would tell me that he had his eye on certain young people in the tribe, and he would run it past the older people. Then he would have me go talk to them and ask for help. This was a way of recognizing that you can’t do all this without the young people being trained as you do it. So, we showed several of the tribal youth how to take pictures and inventory items. One of the first things we focused on was baskets. Then they learned how to interview, translate, and transcribe. As we went along, we added more young people.

What challenges did you face when first launching these efforts?

Linda: Over the years, there were several researchers who gathered oral histories or took pictures and never brought the tribe copies. So when we started, initially it was very difficult to make sure people understood the purpose, but then it wasn’t so bad. I think part of the process was having opportunities for tribal people to be involved in the work.

Aerwyn Fontenot, age 11, adorned in a jingle dress trimmed in jingle cones hand-rolled by her uncle Leland Thompson and father Elam Fontenot, dances at Camp Coushatta. Her mother, Raynella Thompson Fontenot, a Coushatta Tribal Archives staff member, made many of the other regalia components by hand.

What is the process for finding and acquiring materials?

Linda: We started trying to gather this information by asking the community if they could remember any researchers who once came here. Then we would go and track down their papers, recordings, or photographs, and bring copies back.

On the local level, Bertney put the word out and people would call. We asked the community what was important to them and many said baskets, so that is why we have a collection of basket makers’ interviews that we gathered ourselves. As we did that, we also asked, “Where did you trade baskets? Do you remember names of people who purchased them?” Then we would go track those people down. If they had passed away, we would locate their descendants and interview them.

On the national level, I contacted the big archives. I also worked on tracking down scholars who wrote papers on the tribe. If they were alive, I contacted them and asked if they could send me copies. I also went to major archives and talked to people in each of those places and got them to buy into what we were doing. I contacted someone at the Smithsonian and asked for his help. Once we got to Washington, DC, we got on the bus and rode around to find the objects that were purchased from the tribe by anthropologist Mark Harrington in 1908. Harrington recorded the names of who he bought the items from and the prices he paid. So I was able to share that with tribal members: “This was your great grandmother’s basket. He went to her house and bought it for this much money.” The Holy Grail for me was Harrington’s 1908 notebook that had never been located. We went from department to department looking for it and finally found it. The Smithsonian called the whole thing “digital repatriation” and charged me below their cost per page [for scans of the notebook]. Another example is when a tribal member told me about a man who had come and recorded her dad in the 1960s. I was able to track down his recordings that had been mislabeled as “Italian.” I told the archivist, “I really believe these are Coushatta because I know this researcher was in Elton that summer.” It was worth it because it was Coushatta. These items are just priceless to the tribe.

Sixteen-year-old Ethan Sylestine dances in regalia made by his grandfather, Curtis Sylestine, at Camp Coushatta, a summer program designed to strengthen younger tribal members’ connection to tribal traditions.

Has the community contributed much to the tribal archive?

Linda: Yes, they have. We can scan photographs and return the originals to them or we can clean a basket, tag it, and then return it to them. They realize that they don’t have to give away their prized things. Also, we went house to house. We even went to a nursing home and Bertney said, “We want to start something for the tribe by collecting recordings, videos, photographs, and books. We will collect these things, and they will stay here. If you want to record something for your grandchildren, we’ll keep it for you. If you like, we won’t even look at it.” We have been given things that we haven’t cataloged for general access because they are just being kept for that family. In the early years, linguists and ethnographers asked the wrong questions. It is so different when you start with “What do you want to say?”

Bertney: One time we brought in an elder who forgot the camera was there and we just had a conversation. It was so natural.

Linda: Those recordings were done back in the 1980s—twenty years before the language committee [formed]. So we stored them at our home until 2007, when the tribe gave us some trailers to serve as our offices. The language project was the impetus that pushed us to find a centralized place for the tribe to store its historical documents.

What are the future plans for the tribal archives?

Linda: We have a three-year plan that includes an outward-facing searchable portal with different levels of permissions for accessibility to items that will also keep certain things protected for tribal members. That lets somebody access what we’ve put together without having to come in our office, particularly for tribal members who live further away. Another dream for me is that things will be stored in such a way that we know for sure it will live regardless of natural disasters.

Bertney: I would also like to see this information accessible so tribal members know where we came from, where we are at, and where we are going. Also, I would like to see the tribe teach our history and language to the young people. Later, as we get all that information cataloged and written up, we can have a workshop for teachers. We can teach them about who we are, so they can look to that when teaching children. This can happen locally at first, but then target a statewide audience. We can show them what a sovereign nation is all about.

Denise E. Bates is a historian and assistant professor at Arizona State University who has authored several books and articles on the history of the Native South in the twentieth century. She collaborates with the Coushatta tribe on several projects and has contributed to the further development of the tribal archives while working on her forthcoming book, Basket Diplomacy: Leadership, Alliance-Building, and Resilience among the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, 1884–1984, due to be released in February 2020.