Summer 2015

The Follies of a Film Economy

A century prior to New Orleans being dubbed “Hollywood South” for its thriving movie industry, the Crescent City was poised to become a major center for silent film studios

Published: October 1, 2017

Last Updated: December 19, 2018

Today Louisiana is home to the third-largest film economy in the United States, an outgrowth of one of the most generous packages of public incentives ever offered for audiovisual production in the country. More than $170 million in tax revenue, proponents of the incentives say, is a small price to pay for an industry that will generate new investment, high-paying jobs, and positive publicity for otherwise struggling local economies. Yet these claims are nearly a century old, echoing the siren song of the silent film economy of the past and giving some practical warnings for such strategies today and in the future.

The longest-sitting mayor in New Orleans history, Martin Behrman (1904–1920) was keen to jump-start film production at the turn of the last century. Still crippled by its Civil War debts and facing impending bills to construct vast new infrastructures for roads, sewerage and transport, the city was desperate to attract new investment. Like many Southern cities, it needed to promote itself as modern, open for business, and self-sustaining. By this time, New Orleans was already a regional capital for film exhibition and distribution, so Behrman saw a homegrown film industry as a good fit for the city. Two New Orleans newspapers, the Daily Picayune and the Item, had daily sections to cover film shooting schedules and budding celebrities, in return for exhibitor advertising dollars. A production economy would further promote people and places in the city, while giving local movie theater moguls Josiah Pearce and Herman Fichtenberg an edge in expanding their operations nationally.

Pioneers of early film flocked to New Orleans yearly to revel in the public spectacles of Carnival, but it was Behrman’s administration that regarded film production as a possible handmaiden to other business interests. His Association of Commerce took charge of boosting film production, both organizing public events for filming and streamlining the permitting of public space for film crew uses. Pearce was a particularly close ally of Behrman’s, making arrangements for a series of industrial documentaries that would portray the “progressive little city” in charge of the port in a positive light.

Outside filmmakers, however, could not be trusted to share Behrman’s vision. The Association of Commerce contracted a Denver-based company in 1914 to make a series of films that would show Northern audiences “of a certain class … the real reconstruction that is in progress,” but the company went bankrupt before it could distribute these scenes of commercial and industrial renewal. Worse, those film producers who did succeed in bringing New Orleans to the big screen elsewhere did not always portray the city as its leaders would have hoped. In one well-publicized incident, local elites welcomed a French director who then disastrously announced he would use “hoodoo niggers” from the city jail to make a series of shorts about voodoo practices in the Congo. The director then fled, or perhaps was run out of town, to the dismay of the local investors in his film projects.

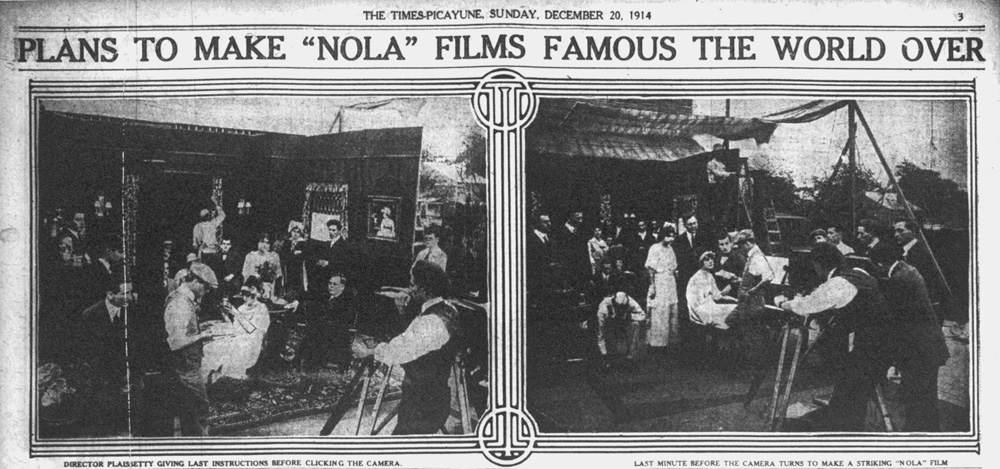

Instead, the fervor prompted the development of a locally sited film economy. A series “of some very wealthy men,” including the general manager for the Association of Commerce, M. B. Trezevant, formed the investor base for the project. A lengthy newspaper story disabused readers of the notion that local film production was merely a diversion: “It is distinctly a business—a serious, manufacturing, money-making business. A small group of New Orleans men were shrewd enough to see it, and a close corporation was formed.” They estimated that their New York connections would generate $2,000 weekly in film licensing sales to theaters nationally, but 75 percent of the revenues would remain in the city. The company began as the Coquille Film Company, but, after the unfortunate incident with the French director, became incorporated as the Nola Film Company in 1915 under the direction of William J. Hannon. Even this name change was auspicious for promoting the new economy. Explaining to readers that Nola stood for N.O., La., “the heads of business figured long on the best way to announce to the world that New Orleans is making picture films. … And does not ‘Nola’ sound like a pretty Creole girl?”

In theory, Nola represented everything its elite backers could ask for. The company was both a tool for place-making propaganda and business development funded from outside the city. Trezevant boasted the studio would lure investors from New York and Europe to the only “purely-local motion-picture manufacturing corporation in the South,” becoming a valuable asset for “advertising the city and the state” and generating salaries and purchases that rank with “some of the largest manufacturing plants in the city.” National ads promoted Nola’s rental facilities and production capacities as filmmakers who continued to flock to the city announced interest in opening a New Orleans studio. Promoters repeatedly stressed to outsiders New Orleans’ diverse shooting locations, Old World charm, and new-world amenities. Behrman claimed that his city was the most hospitable for studios, offering incentives mutually advantageous to filmmakers and the city.

In these 1914 photographs from the Times-Picayune, film director René Plaisetty is seen giving final instructions to a cast before clicking the camera at Nola Film Company. Image courtesy Louisiana Research Collection.

Nola also cultivated connections among small business owners, newspaper advertisers and labor groups. It became a poster child for the short-lived M-I-N-O campaign that urged citizens to choose products “Made-in-New-Orleans.” A former reporter himself, Trezevant ensured the triangulation between positive newspaper coverage with the commercial and union leaders he represented in the Association of Commerce. The Times-Picayune and the Item touted the high quality both of Nola films and of the local entertainment professionals and residents who donated their time, talent and homes for film production. Local payroll expenditures were also published. Nola then prevailed upon businesses to advertise “your plant, factory or store” with its “expert cameramen” and “highly trained artists.” In return for Nola’s investment in the city, M-I-N-O campaigners asked residents to see their films: “Ninety percent of its expenditures go to New Orleans people and only two percent of its income comes from the same source.” From production to consumption, campaigners argued, Nola was to be the anchor holding a chain of other businesses in the city, chiding those who ignored how pioneers of “the photoplay industry put Los Angeles on the map.”

However, Nola lacked some fairly important elements to create a self-sustaining film economy. In the process of building its stature among local businesses, Nola lost its connections to national distributors and financiers that would invest in a film cluster. Although Nola films would screen at a few minor theaters around town, Hannon was unable to ink a deal for national exhibition, or even through the regional chains based in New Orleans. Lacking widespread distribution, the company depended wholly on its local stockholders to foot the bills. Desperate for outside recognition, Hannon signed what would appear to be a mock distribution contract with a fly-by-night company in New York City, just before declaring bankruptcy in 1916. As would become evident in other cities at this time trying to seed a film economy, civic boosterism may encourage local incentives for film production, but it alone can never sustain production industries.

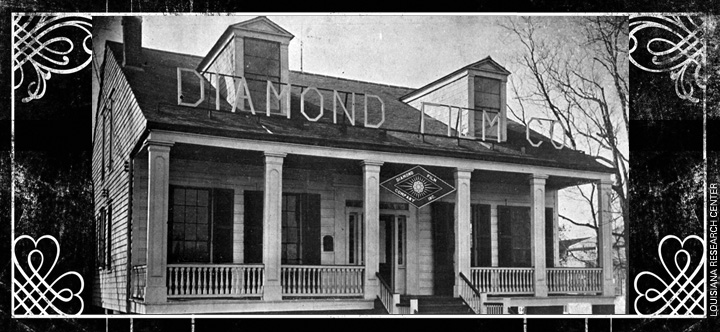

Whether Hannon was trying to shield Nola’s money from its creditors or was legitimately hoodwinked by a shady distribution deal, he retained the operation’s house and studio headquarters on Bayou St. John and opened the Diamond Film Company at the same site in 1918. In an investor booklet for the initial stock offering, Hannon once again deployed the rhetoric of a film economy built on high-paying jobs, business synergies, and the positive marketing of the city. Echoing the Progressivist visions of the Behrman administration and the protectionist pleas of the M-I-N-O campaign, he claimed that New Orleans had both the modern infrastructure and local talent for film production. Perhaps most daringly, he claimed that by buying a $10 share, any individual would ensure New Orleans’ competitive advantages as a movie capital that would rival both Los Angeles and New York.

Despite such pronouncements, Hannon probably began Diamond already in the red. Nola had boasted its laboratories were “the best equipped in the South,” but it had to send its film stock to the North; a newspaper report at the time waffled that the studio “could be turned into a splendid and complete producing plant.” Hannon’s booklet did not display any actual equipment for film making or processing. Whatever assets were associated with the studio were liquidated at an auction a year after its well-promoted launch. The studio was to be demolished and sold for scrap. In two separate court filings, Hannon sued Diamond’s board of directors for nonpayment of bills and countersued the contracting company it owed for renovations. This debt was approximately the same amount Nola was said to have invested in its studio four years earlier.

This is not to say Diamond was not meant to be profitable. Diamond’s board of directors and Hannon built their own fortunes on real estate speculation. Both the lands surrounding the studio and the few movie theaters that showed Diamond films experienced a boom in housing sales and land values. Some of these investors were convicted for an oil drilling scam; although seemingly unrelated, the receivership proceedings for Diamond coincided with the state’s issuance of the criminal indictment. Bankruptcy allowed Diamond officials to liquidate the appraised (and inflated) value of the studio’s lands to pay themselves. Diamond stockholders were left holding the bag.

New Orleans’ dreams of a movie capital were dashed for nearly a century when the state revived them through the 2002 film investor tax credit program. Much like Behrman and his men, film economy boosters today imagine a perfect union of business interests to save a flagging economy. Much like the earlier era, the value of film production is largely speculative, tied to property values and subject to corruption. One would hope that this time Louisianans have learned their lesson from the past because unlike the unfortunate investors in Nola and Diamond, if the new bubble bursts, it will be all taxpayers who lose.

—–

Vicki A. Mayer, Ph.D., is the Louise K. Riggio Chair of Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship at Tulane University. She is the author of Below the Line: Producers and Production Studies in the New Television Economy (Duke University Press, 2011) and Producing Dreams, Consuming Youth: Mexican Americans and Mass Media (Rutgers University Press, 2003).