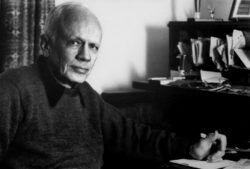

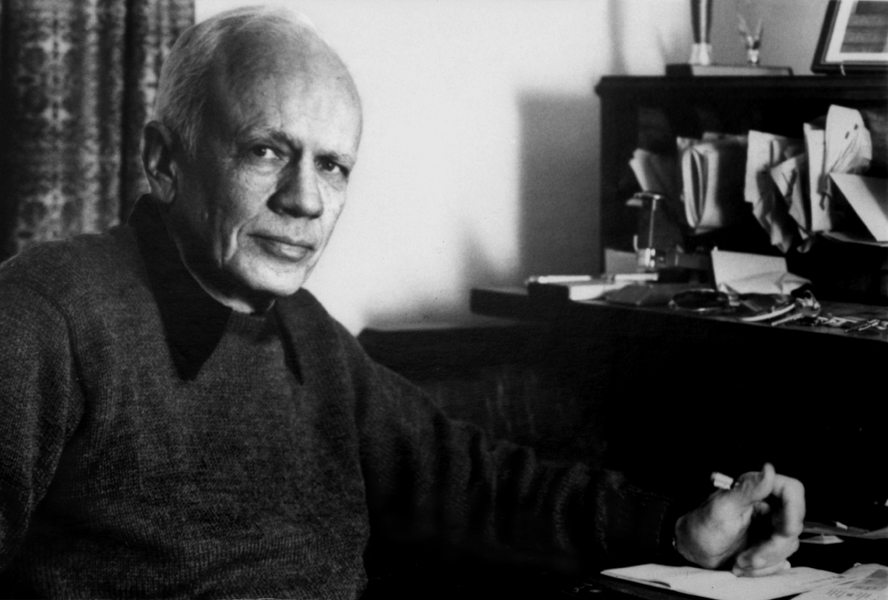

Walker Percy

Walker Percy incorporated the culture and traditions of Louisiana in particular, and the South in general, into his literary work.

The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Reproduction of a black-and-white photograph of Walker Percy.

Though born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised primarily in Mississippi, writer Walker Percy spent the majority of his artistic career in Covington, Louisiana. The author of six novels, two books of critical essays, and one book of nonfiction, Percy became one of the most popular and critically acclaimed writers in late-twentieth-century American literature. He won the National Book Award for his first novel, The Moviegoer, published in 1961. An avid philosopher aligned with the Christian Existentialism of Søren Kierkegaard, Percy rejected the label “regional” or “southern” writer as limiting. While exploring ideas and issues with broad appeal, Percy incorporated the culture and traditions of Louisiana in particular, and the South in general, into his work.

Early Life

Born May 28, 1916, Walker Percy was the son of LeRoy Pratt Percy, a lawyer, and Martha Susan Phinizy. When Walker Percy was young, his father took his own life, and two years later Percy lost his mother in a car accident, also suspected to be suicide. Consequently, Walker Percy spent much of his childhood under the tutelage of his uncle, the noted Southern intellectual William Alexander Percy in Greenville, Mississippi. After attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Percy went to medical school at Columbia University. As an intern at Bellevue Hospital, Percy contracted tuberculosis, an event that changed the trajectory of his life and career. During a brief stay in a sanatorium, Percy read a variety of European existential writers, eventually concluding that science could not explain fundamental questions about man’s existence and purpose. Percy shifted his attention to writing, as a result, and returned to the South, where he married Mary Bernice “Bunt” Townsend in 1946. The couple converted to Roman Catholicism and built a home in Covington, where Percy established himself as a writer and cultural critic.

Themes in Percy’s Work

Given Percy’s life-changing sickness, it is perhaps not surprising that many of his characters are sick: either physically ill or afflicted by a mental malaise that isolates them from the “normal” world. In the 1966 novel The Last Gentleman, the main character, Will Barrett, spends his days watching people through a telescope, afraid to interact with anyone. Though he does not have a specific medical diagnosis, Will constantly blacks out and wakes to find that he cannot remember where he has been or what he has done. Eventually, Will goes on a road trip with a terminally ill young boy named Jamie, hoping to discover himself in the process. By the end of the novel, Will learns, among other things, that the key to curing his mysterious metaphorical sickness lies in interdependence and community.

In Percy’s first novel The Moviegoer, his main character, Binx Bolling, suffers from the same kind of psychological malaise as Will. Unable to experience life directly, Binx spends his days daydreaming or watching movies of others’ lives. It is only through a purposeful engagement with his psychological sickness that Binx begins to discover who he is and how to live his life.

Like Flannery O’Connor—another famous Southern writer with whom he felt an immense connection—Percy’s Catholicism shapes much of his writing. Percy was particularly concerned that American (and especially Southern) culture anesthetized religion and reduced its transformative power. In his nonfiction writing, including the essay “How to Be an American Novelist in Spite of Being Southern and Catholic,” Percy articulated the difficulty of asserting religious identity through fiction. He also insisted on the possibility that true faith could redeem what Percy saw as an increasingly alienated, secular modern world. In this belief, Percy felt a particular affinity for the writings of Søren Kierkegaard. Throughout his work, Percy uses the philosopher’s language (including words like “despair,” “sickness,” and “fear and trembling”) to suggest modern humanity’s need to rely on the “leap of faith” to cure its metaphorical sickness.

Language itself was another of Percy’s interests. Perhaps because his younger daughter was born deaf, Percy became fascinated with linguistics, the science of language, and semiotics, the study of signs and symbols. He published several articles on the subjects, some of which are collected in The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other (1975) and Signposts in a Strange Land (1991). Percy also explored language and symbolism in his fiction, frequently criticizing their manipulation by those attempting to hide or obscure the truth.

Percy’s Legacy and Significance

In addition to his importance as a writer, Percy also influenced and inspired many Louisiana novelists and artists. Notably, at the behest of the author’s mother, Percy helped get John Kennedy Toole’s novel A Confederacy of the Dunces published. Released in 1980 with an introduction by Percy, the novel established Toole as an important Louisiana writer more than a decade after his suicide.

Percy also, of course, created a unique image of Louisiana in the minds of his many readers. In most of his fiction, Louisiana is represented as a kind of paradox: part of the South, yet strikingly unique. Percy’s writing suggested that Louisianans had Southern qualities that, he felt, were disappearing elsewhere, including the importance of community, the celebration of multiple cultures and perspectives, and an emphasis on religion and tradition. Yet, at the same time, Percy refused to become overly nostalgic about the Old South, repeatedly satirizing those who clung to outdated traditions in a changing world. This unique ability to express broad religious and philosophical concerns through regionally specific characters and settings is the quality for which Percy is best known and remembered. He died in Covington on May 10, 1990.