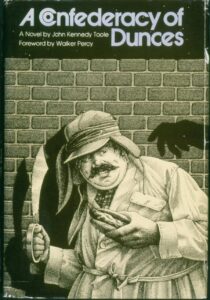

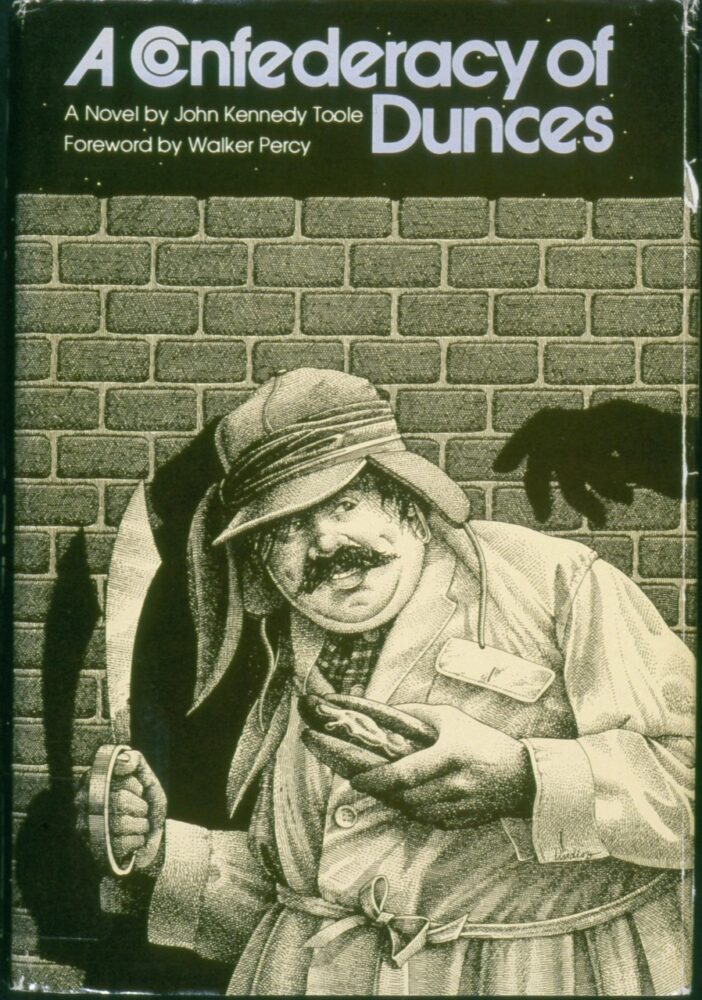

A Confederacy of Dunces

Despite the difficulties John Kennedy Toole faced while trying to publish A Confederacy of Dunces, the novel went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and sell more than two million copies.

THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

Book jacket cover of "A Confederacy of Dunces" printed by LSU press in 1980.

Novelist John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (1980) is one of New Orleans’s most iconic, beloved, and bestselling books. The satirical, episodic novel traces the madcap travails of Ignatius J. Reilly—and an equally eccentric cast of characters—as he searches for a job, a sense of purpose, and perhaps even love on the streets of 1960s New Orleans.

The plot of A Confederacy of Dunces is simple yet sprawling. Ignatius lives with his pitiable, put-upon mother Irene, who encourages her son to do something besides the things he loves to do most: watch movies, masturbate, and write long, convoluted letters to a possible paramour-turned-rival named Myrna Minkoff. Ignatius reluctantly searches for work, first at the Levy Pants manufacturing plant and then selling Lucky Dogs on the streets of New Orleans’s French Quarter. Skewering the countercultural rebellions of the 1960s, Ignatius uses his positions to wage illiberal social revolutions under the guise of race, labor, and gay liberation. He fails as a revolutionary and loses both jobs but finds love in the end.

The central strength of Toole’s novel is Ignatius’s voice and personality. He is arrogant, odious, gluttonous, obese, flatulent, arguably brilliant, and more than a little delusional. He spends his hours railing against a society, as he sees it, full of “perversion and blasphemy” and a people with a “shocking lack of taste and decency.” He happily envisions a world that understands “only strength and force” yet pleads mercy from the goddess Fortuna, whom he believes controls his destiny with her great spinning wheel. As evidenced in the novel’s epigraph from Jonathan Swift, Ignatius believes that the planet is populated by “dunces” who are “all in confederacy against him.”

Born in New Orleans in 1937, Toole, like many novelists, trawled from his own life to create his comic classic. Growing up in the Crescent City illuminated much of the book’s atmosphere. Writing for high school and undergraduate newspapers helped Toole hone the novel’s wit and humor. He labored in a clothing factory and as a pushcart vendor, just as Ignatius briefly does.

Toole loved the French Quarter—then a shambly, untouristed neighborhood—and its oddball cast of characters, who would later become his titular dunces: the inept police officer Angelo Mancuso; Lana Lee, shady proprietor of the Night of Joy bar; the stripper and parrot wrangler Darlene; and Burma Jones, a Black man struggling to dodge the city’s long-lasting legacies of Jim Crow.

Graduate studies at Columbia University put Toole in touch with beatnik feminists like Myrna, with whom Ignatius enjoys his contentious yet flirtatious epistolary friendship. An English department colleague at the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette) inspired Ignatius’s slovenly appearance and obsession with the Medieval philosopher Boethius.

After being drafted into the army in 1961, Toole wrote the bulk of what would become A Confederacy of Dunces while stationed in Puerto Rico. He submitted the manuscript to the Simon & Schuster publishing house in 1964 and worked unsuccessfully for the next several years to publish the book with senior editor Robert Gottlieb. Suffering from depression, excessive alcohol consumption, and distraught at being unable to see his novel in print, Toole committed suicide in 1969. He was 31 years old.

What happened next is one of the strangest stories in publishing lore. Toole’s mother Thelma, who bears more than a passing resemblance to the brash and theatrical Ignatius, sent the manuscript to several uninterested publishers before putting it in the hands of Walker Percy, New Orleans’s then-eminent author. As he writes in the novel’s forward, Percy read “first with the sinking feeling that it was not bad enough to quit, then with a prickle of interest, then a growing excitement, and finally an incredulity.”

Percy championed the work, circulating it among his students, getting an excerpt published in the New Orleans Review, and appealing to several publishers before submitting the manuscript to Louisiana State University Press, which published the novel in 1980 with a small print run of twenty-five hundred copies. The following year, in a shocking denouement, A Confederacy of Dunces won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Toole’s posthumous masterpiece has sold more than two million copies in more than two dozen languages. In 1996 the city unveiled a bronze statue of Ignatius—wearing his trademark muffler and hunting cap—on Canal Street, in front of the former D. H. Holmes department store, where the novel begins.

Despite several successful local and national stagings, Hollywood’s attempts to turn Toole’s novel into a film resembles nothing if not a spin of Fortuna’s wheel. Whether due to the vagaries of the Hollywood production schedule or whispers that the film is cursed, numerous enticing director and Ignatius pairings have all come to naught.

A Confederacy of Dunces keeps finding readers and critics, lovers and haters. In a 2016 essay Maurice Carlos Ruffin transports Ignatius to a very different, twenty-first century New Orleans to examine issues of race, gender, and gentrification. In a New Yorker essay, Tom Bissell sees Ignatius as a precursor to today’s reactionary, unreconstructed Internet troll.

Whatever we think of Ignatius J. Reilly, A Confederacy of Dunces will not only continue to enjoy its lofty status as the New Orleans novel to read to appreciate a city and its people — despite the vast changes that have occurred — but will also rank as one of the great stories in American literature.