Great Depression in Louisiana

Louisiana was deeply affected by the Great Depression when cotton, sugar, oil, and timber values plummeted, and the port of New Orleans experienced a precipitous decline in foreign trade.

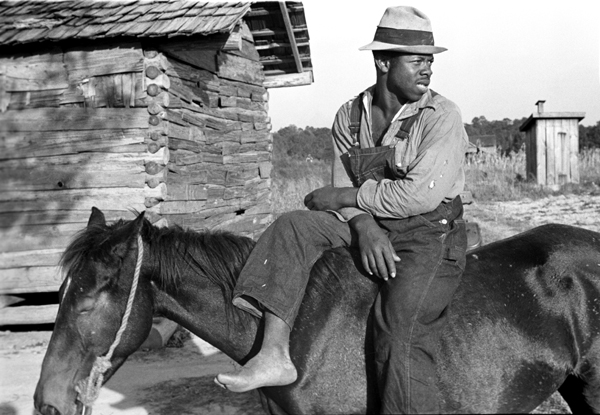

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Black-and-white reproduction of a 1935 photograph, "Strawberry Picker, Hammond, Louisiana," by Ben Shahn.

T he Great Depression is widely attributed to the ongoing post–World War I economic malaise that engulfed Europe and the rest of the globe during the 1920s. In the United States, however, the dazzling growth of new technologies and the rapid advance of consumerism during the Jazz Age suggested that America was somehow immune to the chaos of the outside world. Yet protectionist trade policies, unchecked speculation, declining real wages, and the crisis of overproduction in industry and agriculture combined to undermine the soundness of the American economy by the end of the decade.

These profound structural problems periodically revealed themselves, most notably with the real estate busts in California and Florida during the mid-1920s. In the popular mind, though, they seemed to crest all at once with the October 1929 collapse of the stock market, which fell to pieces after a remarkable yearlong run. By the end of the month, it had lost an estimated 40 percent of its total value. Although rallying somewhat in early 1930, which gave President Herbert Hoover and the investing classes a glimmer of hope, the market quickly resumed its disastrous slide, reaching a low in the summer of 1932, just before the presidential election that fall. It would not recover to its pre-Depression levels until the 1950s.

The shocking losses in the stock market soon rippled out into the wider economy, with more than 1,300 banks failing during 1930 alone. In a larger sense, though, the disintegration on Wall Street simply reflected the slow-moving nightmare that was the national economy. More than 26,000 businesses failed in 1930, followed by even more in 1931 and 1932, the highest per capita bankruptcy rates in American business history. Private investment in manufacturing dropped more than 80 percent, while foreign trade fell by 70 percent. By 1933, the US gross national product had been sliced by more than half from its 1929 peak, with the physical output of American industry falling to 1913 levels. In short, within three years, all the gains of the World War I years and the 1920s had been completely erased.

Depression-Era Louisiana

As a mostly agricultural state in the Deep South, Louisiana was greatly affected by the slumping economy, especially as farm prices declined to unheard-of lows. Cotton, for instance, dropped to less than five cents a pound, sugar to less than four. The value of the state’s other leading commodities—timber, oil, and rice—experienced a similar erosion. Although the vast majority of the rural population already lived in grinding poverty, the worsening conditions of the Depression pushed people to extremes. Further, the calamitous 1927 Mississippi River flood and the 1930–31 drought had displaced tens of thousands of farm laborers and their families (and many more from neighboring states), most of whom had yet to find a settled place in Louisiana society.

Traveling through Tensas Parish in the fall of 1933, relief fieldworker Lucille Watson found one of these families living in a plantation shack, the walls of which were “one big crack” that had been pasted over with old catalogue pages and newspaper to keep the “wind and the rain from blowing into the house as much.” Elsewhere, she found another migrant family with a mother who was “depressed and miserable over their present condition” and children who “looked more or less sick and puny.” In other cases, Watson stumbled upon families with only a few bushels of sweet potatoes to last the winter season. Hard times, then, abounded in the state’s rural areas. Even the upper classes, planters and large landowners, faced difficult prospects as farm income declined by two-thirds between 1929 and 1932. Many could not pay their taxes or keep up with their mortgages, eventually losing everything to the dreaded sheriff’s sale or to foreclosure by insurance companies and banks.

Yet rural distress hardly accounted for all of the suffering during the Depression years in Louisiana. The oil and natural gas industry, though more resilient than manufacturing, nonetheless endured a slowdown in production that necessitated cutbacks and layoffs. Still, the oil business proved a bulwark of sorts for the state’s economy throughout the 1930s, especially after a true recovery had gotten under way by 1934–35. Baton Rouge, home of the Standard Oil refinery and associated plants, continued to expand during the decade, as did Shreveport and Monroe, both nestled in the midst of vast petroleum fields.

New Orleans, however, experienced some of the worst aspects of the Depression in the state, more akin to the anguish felt in the metropolises of the north than in the city’s rural hinterlands. The south’s largest urban center in 1930, and still one of the nation’s biggest ports, New Orleans came face to face with the specter of the Depression almost immediately. With the precipitous decline in foreign trade, New Orleans’s warehouses emptied and its docks fell silent; the army of stevedores and handlers that serviced America’s, and the world’s, agricultural and industrial production, lay idle. By early 1930, in fact, one census counted at least 10,000 unemployed workers in the city, although the true figure was probably much higher. To handle the pressures of public relief, the city formed a Welfare Committee in early 1931 and raised more than a half million dollars from private sources. When this money ran out in 1932, municipal leaders floated a $750,000 bond issue, but this likewise proved insufficient to deal with the mass of the unemployed and their families.

Yet, on the whole, Louisiana perhaps suffered less than other parts of the nation. The state’s governor, and later US senator, Huey Long, had made a commitment to infrastructure development when he took office in 1928, and his willingness to expend millions of dollars on massive construction projects blunted the full force of the national collapse, while also foreshadowing the thrust of the New Deal itself a few years later. Without the benefit of economic advisors or political scientists, Long instinctively pressed for increased spending in all areas of state government to stimulate economic growth. He built roads, bridges, and public facilities at an amazing clip and bolstered public education through the distribution of free textbooks, teacher pay raises, and adult literacy programs. Between 1928 and 1932, in fact, Long spent more than the previous three state administrations combined.

Oddly enough, though, public relief was not something that Huey Long ever endorsed, or ever really was forced to support. His early construction program poured money into public works projects that provided employment opportunities for many laborers around the state, while after about 1931, when he began to move into the national political picture, he cared more about maintaining his base of power in Louisiana than providing for his constituents. Local sources of public charity carried much of the load through then. In fact, churches, social clubs, benevolent societies, and other private sources had contributed more than 98 percent of all welfare expenditures in the state that year. And by the time these sources began to give out, even the Republican administration of Herbert Hoover had seen the necessity of a national relief program.

The Depression Lifts

Beginning with Hoover’s issuance of federal loans to the states in the late summer of 1932, a more regular approach to relief took shape. Between October 1932 and May 1933, Governor O. K. Allen’s administration paid out $6.5 million in these funds while handling approximately 115,000 cases a month. Once Franklin D. Roosevelt took office as president in March 1933, this system was reorganized under the control of the Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA). Following this, federal dollars flowed into the state at an impressive rate and, although often manipulated at the local level, nonetheless made a powerful impact on the state’s relief problems. Later, after Long’s death in 1935, an even greater amount of money cascaded into Louisiana for projects that eventually employed thousands of blue- and white-collar workers.

With the onset of the federal relief and recovery programs known collectively as the “New Deal,” the Depression in Louisiana transformed into something less desperate, less purely terrifying. Although poverty and underemployment continued to mark the lives of many of the state’s working-class families up until the onset of World War II, the crisis situation of the early 1930s had abated. Indeed, among many Louisianans, the latter half of the decade emerged from the haze of memory as something of a golden era, a time of common purpose and feverish activity that saw major architectural undertakings and an outpouring of the arts. Among these were the restoration of the French Market in New Orleans and the building of the Louisiana State Exhibit Museum in Shreveport, as well as the creation in public venues of a wide variety of murals celebrating Louisiana history and life and the production of the richly detailed Louisiana and New Orleans guidebooks under the direction of noted author Lyle Saxon. Yet, if one takes the time to read the deep anxiety and fear that permeated Louisiana newspapers and private correspondence during the early years of the Depression, one is reminded that this was indeed America’s most perilous time.