Oil and Gas Industry in Louisiana

The oil and gas industry has been a dominant economic engine in Louisiana for well over a century.

Wikimedia Commons user Edibobb

Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, Pumping Platform Complex.

The oil and gas industry has been a dominant economic engine in Louisiana for well over a century. It has shaped the social, political, economic, and environmental landscape in the state for generations. All sixty-four parishes in the state, at one time or another, produced oil and gas. Historically, the industry generates about a quarter of the total state revenues and provides jobs for tens of thousands of workers. Louisiana consistently ranks among the top producers of oil and gas and refining capacity in the nation. The state is a “launching point” for the offshore oil and gas industry, and as such, it has played a vital role in American energy security. While the economic benefits derived from the industry have endured for decades, so have the social and environmental costs associated with oil and gas activities.

Louisiana’s Energy Coast

Due to its unique geological and geographic features, the southern region has borne the brunt of energy development in the state. Spread out across the vast coastal plain and just offshore are hundreds of salt domes, mostly buried deep beneath the surface, where vast pools of petroleum could be found. Exploration and production around these salt domes led the industry from the coastal prairies to the low-lying marshes, bayous, and shallow bays and lakes along the fringe of the Gulf of Mexico and eventually into the open Gulf itself—all in search of hydrocarbons. A network of platforms, pipelines, storage facilities, industrial parks, deepwater ports, and navigational channels had to be built along the coast to accommodate the needs of the growing industry. Hundreds of locally owned companies sprang up throughout south Louisiana to provide essential support services to the oil and gas companies. These homegrown oilfield service companies have been the backbone of the state’s energy sector; they specialized in construction, marine transportation, shipbuilding, fabrication, drilling equipment, and tool rentals.

Early History

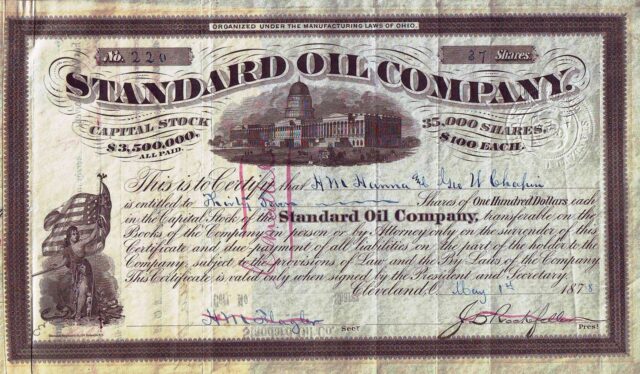

Louisiana’s oil and gas industry began in 1901 with the successful drilling of the first oil well near the town of Jennings in the southwestern countryside. While development commenced slowly around a handful of salt dome fields in the south, new discoveries at Caddo Lake, De Soto–Red River field, and the prolific Monroe gas field shifted the industry’s attention to the parishes farther north. The major discoveries in the northern parishes set off a boom in the early decades of the century. Much of the oil produced from the northern fields had access to the state’s largest pipeline system and refinery, owned by Standard Oil in Baton Rouge. Within a few years, the majority of these northern fields played out. With the advent of new seismic technology and marine-related equipment, the oil companies redirected their focus on the southern salt dome fields. With the discovery of several new salt domes in the late 1920s, production of oil and gas in the southern part of state eclipsed that of the north. For the remainder of the century, coastal oil and gas development led the way for the state.

Coastal Oil and Gas Development

By the 1920s, oil men discovered that underground salt dome formations spread out across the entire Gulf Coast contained pools of oil and gas in concealed faults and sediment traps. With the use of new geophysical instruments, companies located many of these buried salt domes in watery areas inaccessible to traditional land-based drilling and production equipment. In 1926, Pure Oil Company discovered the Sweetlake oil field in Cameron Parish—the first commercial production from a well on the Louisiana coast. Early leasing along the coast was not for specific tracts but for specific areas, such as all of Terrebonne Bay. Some of the leases amounted to thousands of acres per area. The size and complexity of the first coastal drilling and production platforms in the shallow bays dwarfed those used at Caddo Lake, where the first open water operations in the southern United States began in 1908.

To fully develop these coastal fields, the industry had to transition to marine-oriented operations. This increased the need for all types of boats, marine equipment, and local mariners to support the operations and progress. The adaptation of the marsh buggy allowed for seismic exploration in isolated wetland areas. By the late 1930s, the oil industry had advanced along the coastal plain at a dramatic pace. Barge-mounted oil field equipment became a key innovation in the evolution of the industry. The invention of the submersible drill barge, perhaps the biggest leap in technology up to mid-century, provided the stability, the versatility, and the re-usability that the industry needed to pursue the expansion of drilling into the marshes and just offshore. Oil and gas discoveries in shallow lakes and bays and tidal estuaries convinced oil men that salt dome fields existed in abundance offshore. The industry adapted this new marine technology to gradually move farther into offshore waters.

Pushing Offshore in the Post-War Era

The growing demand for petroleum at mid-century fueled the continued search for new oil and gas supplies along the Gulf Coast and ultimately into the deep waters of the Outer Continental Shelf several miles offshore from land. In 1947, Kerr-McGee successfully opened the first commercial offshore oil field in the Gulf, about ten miles south of Morgan City. Many engineering problems had to be solved for companies to risk the investments in these unchartered hurricane-swept waters. But in time, research, technological advances, trial and error, and favorable policies ushered in a boom in offshore Louisiana that lasted for many decades.

By the end of the 1970s, the industry had built thousands of platforms and miles of pipelines offshore. For the remainder of the century, south Louisiana became the epicenter for the development of new supplies of oil and natural gas from offshore waters. As such, the state became vital to America’s energy needs. Several national energy-related projects were constructed in the state, including the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the Henry Hub, and Port Fourchon. Thousands of miles of pipelines span the southern reaches of the state that provided a critical link to move the oil and gas supplies from offshore to market.

The oil culture in Louisiana

As the oil industry expanded into more areas of the state and offshore, so did the oilfield service companies. Oil and gas development stimulated all areas of the economy. Never before or since has the state experienced such economic progress as during the post-war decades. The state and local governments received increased tax revenue from the petroleum industry to fund their programs and budgets. Entrepreneurs created new businesses in the oilfield service sector that employed thousands of skilled workers. These companies built and operated barges and boats, supplied the industry with tools and equipment, and provided catering services and warehouses to the vast number of oil and gas companies with operations in the state. The benefits of the boom in the oil-driven economy spread to all sectors of business, including banking, real estate, and car dealerships. The close interconnectivity of the oil and gas industry and society in Louisiana, however, created a deep dependence on petroleum and prices that throughout history has produced hardship and economic calamity.

The cyclical nature of the national and global energy markets often dictated the fortunes of companies, communities, and workers. Recessions and sudden declines in oil demand and energy prices create depression-like economic conditions for the state’s oil-dominated political economy. The “oil bust” of the 1980s led to a severe downturn in the industry that cast a dark shadow over the state for nearly a decade. Hundreds of companies went out of business and unemployment in the southern parishes skyrocketed to nearly 20 percent. Downtown New Orleans experienced a mass exodus of many oil and gas companies that shifted their main Gulf Coast offices and operations to Houston and elsewhere. Bankruptcies, consolidation, and mergers forever altered the energy sector in south Louisiana. When the economic conditions improved in the 1990s, the industry underwent a significant transformation. Most of the inland and coastal oil fields had been depleted and the industry began to focus its operations and investments almost exclusively in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico. The service companies that made it through the oil bust had to adapt in order to survive in the new high-tech deepwater arena.

The revolutionizing shale-fracking technology has, in the last several years, launched a new boom in onshore oil and gas exploration and production, particularly in the north parishes. Hydraulic fracking is a drilling and production technique that uses high-pressure water, sand, and chemicals to fracture rock formations that contain hydrocarbons, thus releasing oil and gas to the surface through a conventional well. The development of these new fields has led to economic progress in areas that had long been abandoned by the oil and gas industry. While the state and local governments continue to reap added benefits from this new industry activity, and service companies expand their markets and work force further north, only time will tell how this new shale industry will continue in the future.

Environmental Issues

Photographer Keely Merritt visited the oiled bird cleaning facility at Fort Jackson, LA, on June 11, 2010. The BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill happened on April 20, 2010. Historic New Orleans Collection

Energy development in Louisiana, particularly along the coast, has come with mixed blessings for some in the Pelican State. On the one hand, it completely transformed the state’s economy. It provided high-paying jobs and improved the standard of living for thousands. But on the other hand, the industry produced unintended and long-lasting environmental impacts. These environmental tradeoffs are an important aspect to the history of oil and gas development in the state.

The construction of thousands of miles of man-made canals in the coastal marshes and barrier islands has contributed to coastal erosion. Experts believe that subsurface fluid withdrawal from petroleum production has led to subsidence, which has compounded the state’s coastal land loss problem. Oil spills, discharges of produced saltwater (a by-product of oil) into waterways, and leaks from open oilfield waste pits have led to contaminated soils, sediments, and surface and ground water supplies. It has also led to degraded wetlands. Hundreds of oil and gas fields throughout the state have been abandoned—primarily in the aftermath of the oil bust of the 1980s—leaving behind old and rusted flowlines, wells, and tank batteries that leaked and polluted the surrounding areas, causing health risks. Without effective cleanup and remediation of polluted sites, the effluents from these contaminants, including heavy metals and other toxic substances, will remain in the environment indefinitely.

For many decades, the industry conducted their standard practices without much oversight, enforcement, or mitigation requirements from the state. Around the 1980s, once these environmental issues became widely known, new attitudes and stricter regulations forced industry practices to change. While the industry’s environmental protection standards have improved, its environmental footprint throughout the state will endure for decades to come.

The scenes of oil-soaked pelicans—the Louisiana state bird—and devastated marshlands and beaches during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill illustrated the real environmental costs that the state has had to deal with throughout its long history with the oil and gas industry.