Standard Oil

In the early 1900s, the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana built one of the largest refineries in the world in Baton Rouge.

Wikimedia Commons

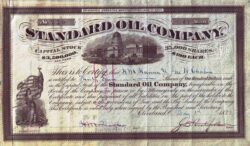

A Standard Oil stock certificate.

In the early 1900s, the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana built one of the largest refineries in the world in Baton Rouge. It also built a robust interstate pipeline system to supply the refinery with oil. Now owned by ExxonMobil Corporation, this major company helped to transform the state’s capital into a metropolis. But in a political context, the company is best known for its enduring regulatory battles with Huey Long, who fought against the oil titan first as the Louisiana Public Service Commissioner and later as governor. The Standard Oil and Long feud lasted for several years and helped to solidify the latter’s political reputation as a progressive and populist reformer.

At the turn of the twentieth century, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil giant had amassed vast sources of crude production in the Mid-Continent region of the United States. But in order to process and market its oil supplies, Standard needed a location for a refinery with access to the nation’s major waterways. The company selected a site on the banks of the Mississippi River in Baton Rouge to build its new refinery complex. In 1909, the parent corporation organized the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana to construct the refinery and the associated interstate pipeline network. Standard’s Interstate Pipeline originated in Baton Rouge and traversed north through Arkansas and Oklahoma to provide a market outlet for the company’s prolific oil reserves in the region. Locating a refinery in Louisiana along the Mississippi River had the advantage of accessibility to ocean-going tankers. The laissez-faire, pro-industry attitude of the state leaders at the time further enticed the company to locate a new facility in Louisiana. Many heralded the historic development as one of the greatest industrial enterprises ever launched in the state.

In its first decade, the company ran its operations with little or no governmental oversight. Standard Oil’s well known and controversial monopolistic business tactics (controlling production, prices, and transportation rates) limited the ability of independent producers in north Louisiana to sell and move their oil supplies to market. During World War I, smaller producers in the region sold their oil to Standard Oil, but when the war ended, so did the need for the surplus oil from the independents. As an up-and-coming lawyer in northern Louisiana, Huey Long represented one of these independent oil firms in the Pine Island field. He obtained a modest share of stock in the company, perhaps as payment for his services. When Standard Oil curtailed its purchases of Pine Island crude, the independents’ stock prices plummeted. Long lost money in the stock plunge and became an outspoken critic of the oil giant. By attacking Standard Oil in public, Long gained notoriety as a fighter for “the little guy” and a voice for corporate reform.

Long battled Standard Oil throughout his entire political career. The company became his favorite political target. He took every opportunity to score political points by casting himself as the hero of the common people who fought against big-business interests in the state. To Long, Standard Oil represented the worst of the American capitalist system and he successfully positioned himself as a righteous corporate antagonist. Long’s relentless pursuit to impose higher taxes on the oil industry—mainly Standard Oil—to fund his public programs, such as free textbooks for school children, solidified his stature as a leading populist and champion of the poor and working class.