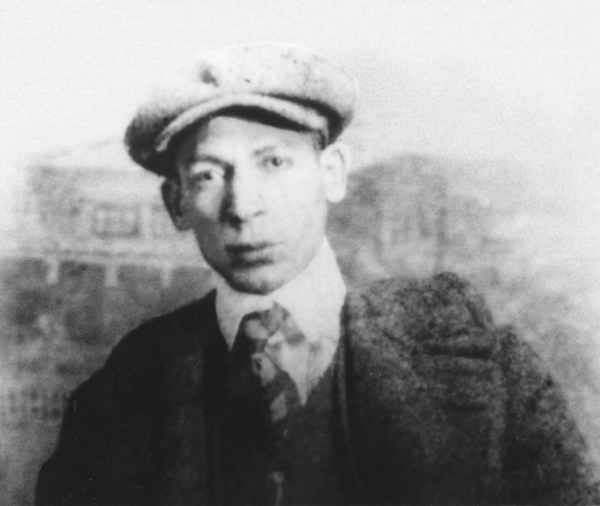

Jelly Roll Morton

Jelly Roll Morton was the first important composer and arranger of New Orleans jazz, as well as an agile pianist, a compelling singer, and one of the early jazz world's most flamboyant characters.

THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

Jelly Roll Morton.

Jelly Roll Morton was the first important composer and arranger of New Orleans jazz, as well as an agile pianist, a compelling singer, and one of the early jazz world’s most flamboyant characters. The nickname “Jelly Roll” was derived from sexual slang, and “Morton” was a stage moniker. His given first name was Ferdinand, and his surname has been variously stated as LaMothe, Lemott, or LaMenthe, while his year of birth was either 1885 or 1890.

Whatever the actual details, Morton came from a New Orleans Creole family who did not approve of his musical aspirations. “We always had musicians in the family,” Morton explained “but they played for their own pleasure and would not accept it seriously, and always considered a musician (with the exception of those who would appear at the French Opera House, which was always supported with their patronage) a scalawag, lazy, and trying to duck work.” As a teenager, Morton began playing in Storyville brothels and also traveling around the South as both a bandleader and solo performer. His trademark compositions from this era include “The Animule Dance,” “King Porter Stomp,” and “Original Jelly Roll Blues.”

Musical Style

Although Morton did not single-handedly “invent” jazz, as he often claimed, he ranks among the important defining figures in its initial evolution. Morton’s eclectic approach consisted of a synthesis of ragtime, classical music (including opera), miscellaneous popular songs, and the blues, among other sources. In Morton’s view, jazz was not some revolutionary new entity but rather, an aesthetic, “a style that can be applied to any type of music,” or more specifically, a style that called for “plenty of finger work in the groove ability, great improvisations, accurate, exciting tempos with a kick.” As for his role, Morton stated, “It was I, that’s the originator of jazz… It was in the year of 1902 that I conceived the idea… It was a style which I had that grabbed the world by the throat with a strangle hold.” No wonder folklorist Alan Lomax commented that Morton’s “epic self-praise antagonized even his admirers.”

In addition to the African and European concepts that commonly converged in jazz, Morton introduced a hybrid of these two traditions that he called “the Spanish tinge,” incorporating Afro-Cuban rhythms such as the rhumba and habañera into his song “The Crave.” This component underscored Louisiana’s connections with Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico culture. Morton had absorbed the “Spanish tinge” via two sources: the work of Louis Moreau Gottschalk, the nineteenth-century concert pianist and composer whose classical compositions incorporated indigenous folk-rooted material, and the street-culture legacy of the erstwhile slave-era gatherings in Congo Square. The “Spanish tinge” and related forms of syncopation were also key components in the New Orleans rhythms collectively known as “second-line” beats, which continue to thrive. In this sense, Morton’s sophisticated playing presaged the more rough and tumble piano style of midcentury blues and R&B artists, including Professor Longhair.

Another of Morton’s rhythmic penchants was the use of “stop time,” which used short intervals of suspenseful silence to build the momentum of a song or dramatically introduce a solo. These diverse elements, along with Morton’s flair for intricate and energetic arrangements, are all evident on compositions like “Black Bottom Stomp” and “Grandpa’s Spells,” which Morton recorded with his Red Hot Peppers between 1926 and 1930. Those recordings, along with a set of solo player-piano rolls from 1923 to 1924, stand among Morton’s best and most influential work.

Later Career

In the 1930s, Morton’s pioneering work came to be considered passé, and his career was in the doldrums. Moreover, like many musicians of the day, Morton did not secure the copyrights for all of his compositions. He was galled to see these songs bring success to other musicians while he earned only partial payment or, in some cases, nothing. “They’re stealing my music and they don’t even play it right,” he complained. By 1938 Morton had moved to Washington, D.C., where he languished in poverty and sickness, performing at a dive for audiences who knew nothing of his illustrious past. One such unappreciative patron stabbed Morton, though not fatally, shortly after he was interviewed by Lomax in 1938. The eight-plus hours of reminiscence and performance constitute an incredibly rich oral history, which finally was released in its entirety on a 2005 CD. In addition to illuminating Morton’s story, the set revealed him to be a poignant blues singer.

Morton continually tried to revive his career until his death on July 10, 1941. Had he lived a few years longer, Morton would have benefited from the first revival of traditional New Orleans jazz. Still, his compositions and contributions to the jazz repertoire have never faded. The past quarter-century has seen renewed appreciation for Morton’s music, especially in New Orleans. Pianist such as Tom McDermott, Steve Pistorious, and Allen Toussaint reprised and explored his oeuvre, while Morton’s rambunctious life has been celebrated in the musical “Jelly Roll,” by Vernel Bagneris.