Congo Square

Congo Square, now Armstrong Park in New Orleans’s Tremé neighborhood, served as a gathering ground for Africans in the early years of the city.

THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

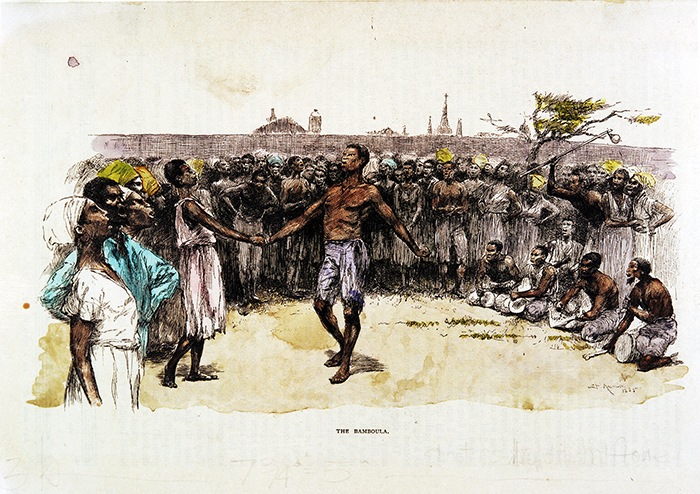

The Bamboula.

Congo Square is a public plot of land located in New Orleans on North Rampart Street between St. Ann and St. Peter Streets. In the nineteenth century, it served as a gathering place where Africans, most of them enslaved, openly enjoyed traditional music, dance, and cuisine of the Mother Continent. Unique in the South prior to emancipation, Congo Square’s cultural milieu has led many scholars to believe it was the very ground that ultimately gave birth to New Orleans jazz. At present, it is situated in the southwest corner of Louis Armstrong Park located in the Tremé neighborhood, the oldest African American neighborhood in New Orleans. Today’s Congo Square encompasses 2.35 acres, approximately one-half the measurement that existed during the nineteenth century, when its most celebrated events took place.

This public space holds a long and diverse history under French, Spanish, and American rule that includes recreational, religious, military, cultural, and political events involving diverse groups of people. However, it was the gatherings of enslaved Africans on Sunday afternoons and the influence of their traditional practices on popular culture that made Congo Square known around the world. This location hosted public performances of African and African-based music, song, and dance over a longer period of time and at later dates than any other public location in North America.

A Place of Performance

The influence of those African cultural practices (rhythmic cells, songs, music, dances, religious belief systems, marketing, and cuisine) on the culture of New Orleans is significant. The rhythms and variations played in Congo Square are found at the core of early New Orleans jazz compositions and became an integral part of indigenous New Orleans music. They are still heard in second line and parade beats, the music and songs of Mardi Gras, or Black Masking, Indians, and the music of brass bands that play for jazz funerals and Black social aid and pleasure club parades.

While the Africans who gathered at Congo Square influenced the indigenous culture of New Orleans, the city’s culture and laws under the various administrations, in turn, shaped Congo Square’s legacy. In 1724, six years after the founding of the French-ruled and Catholic-based city of New Orleans, Louisiana officials adopted the Code Noir, or Black Code, a series of laws that, among other things, established Sundays as nonwork days for everyone in the colony, including enslaved Africans.

No law, however, granted enslaved people the right to congregate, and the privilege for them to do so was constantly under threat. Any effort or rumor of an effort to revolt and gain real freedom jeopardized their ability to come together. Yet, from the earliest days of the colony, under different laws and conditions, Africans gathered at every opportunity. They congregated discontinuously at various locations in the city—along levees, in backyards, on plantations, in remote areas, and in other public squares on Sunday afternoons, until 1817. That year a city ordinance restricted all assemblies of the enslaved for the purposes of dancing and merriment to one location appointed by the mayor. The designated place was Congo Square.

Those who gathered at Congo Square reflected the population of enslaved Africans brought to Louisiana. Under French rule, two-thirds of them originated in the Senegambian region, and others were from the Bight of Benin and the Kongo-Angola region. Under Spanish rule, enslavers brought Africans from the previous locations, with the largest number originating from the Kongo-Angola region, as well as from the Bight of Biafra, Sierra Leone, the Windward Coast, the Gold Coast, and Mozambique. Under American rule, the majority of enslaved Africans brought to Louisiana and the largest number that populated New Orleans were of Kongo-Angola heritage.

Sunday Afternoon Rituals

On Sunday afternoons, gatherers arrived at Congo Square from different parts of the city and from different social and labor categories. There were field hands, domestic workers, those whose owners hired out their labor, and free people of color. Some traveled to Louisiana by way of the West Indies—particularly Sint-Domingue (now Haiti) and Cuba, other slaveholding nations—particularly under American rule, and some came directly from their homeland in Africa.

Initially at the gatherings, and continuing in degrees over time, Africans spoke and sang in their native languages, practiced their religious beliefs, danced in traditional forms, and played African-derived rhythmic patterns on instruments modeled after African prototypes. The music, songs, and dances as well as performance styles in Congo Square paralleled those found in the parts of Africa and the West Indies, where many of the gatherers had resided before landing in New Orleans.

Men, women, and children congregated by the hundreds—some reports say thousands—and formed circles. Inside each circle were dancers and musicians, and those who encircled them clapped, sang, shook gourd rattles, responded to the calls of song leaders, added ululations, and replaced fatigued dancers. The gatherers carried their spirituality with them and honored traditional religious beliefs that informed Voudou religion, which many of them practiced. Some of the principal leaders ornamented their garments with the tails of small wild animals and used animal skin as containment for herbs and objects that provided healing and good fortune. An early observer noted that those with the most ornamentation and who appeared to be the most menacing attracted the largest circle of company.

Musicians played drums of different styles and sizes made from empty barrels and carved-out logs. They played a variety of percussion as well as melodic instruments including the kalimba, banza, panpipes, gourd rattles, balaphons, animal jawbones, and wooden horns. These and other instruments along with designated songs accompanied popular dances including the Calinda, Bamboula, Congo (Chica), Juba, and Carabine.

Over time, as English-speaking enslaved Africans arrived from other slaveholding areas, the gatherers increasingly added European-based musical instruments, songs, and dances. Those instruments included the mouth harp, triangle, violin (fiddle), and tambourine. They danced to “Old Virginia Never Tire” and sang “Hey Jim Along” and “Get Along Home You Yallow Gals.” Yet alongside these additions, gatherers continued to perpetuate and impose many of their traditional practices. The resultant blending of styles and techniques led to the evolution of new styles, indigenous styles, African American styles.

An integral part of the gatherings was the economic exchange, which had enslaved buyers and sellers at its center. The opportunity for enslaved people to earn money on Sundays, their day of rest, enabled them to patronize the market women and other vendors, who sold goods that they had made, gathered, cultivated, and hunted. Popular items included pecan pies, pralines, roasted peanuts, molasses candy, and calas (rice cakes). Beverages included coffee, lemonade, and la bierre du pays, also called ginger beer.

Known by Many Names

Numerous names, official as well as unofficial, identified this location over the years: Place Publique, Place des Nègres, Place Congo, Circus Park, Circus Square, Circus Place, Congo Park, Congo Plains, Place d’Armes, and Beauregard Square. Names that travelers used when writing about the location include Congo ground, Congo Green, the green expanse, and the commons. However, the name “Congo Square” emerged as the most popular one and appeared on maps of New Orleans during the 1880s, although no city ordinance had made it official. Beauregard Square became the official name in 1893, when a city ordinance bestowed the name in honor of Confederate Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard. The popular name “Congo Square” regained prominence and wide usage beginning in the 1970s with the development of the Louis Armstrong Park complex within which Congo Square is located. In 2011 the New Orleans City Council unanimously passed an ordinance that officially named this location Congo Square.

Other events that occurred at this site prior to the Civil War include ball games, horse shows, bullfights, cockfights, foot races, circuses, carriage shows, firework displays, military drills, public executions, and the sale of enslaved people. In 1864 more than twenty thousand people gathered in Congo Square to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation; in 1865 New Orleanians gathered there to commemorate President Lincoln after his assassination.

In the twenty-first century, Congo Square continues to serve as a meeting place for New Orleanians—particularly those of African heritage. Sunday drum circles, family gatherings, weddings, political demonstrations, music festivals, prayer vigils, and gospel performances extend Congo Square’s legacy as a venue of culture, recreation, spirituality, and politics. The first jazz festival was held there in the 1940s. The first New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival took place there in 1970, and the first Congo Square New World Rhythms Festival occurred in 2007.

The National Register of Historic Places listed Congo Square in 1993, and the Congo Square Preservation Society (previously the Congo Square Foundation) placed a historical marker at the site in 1997.