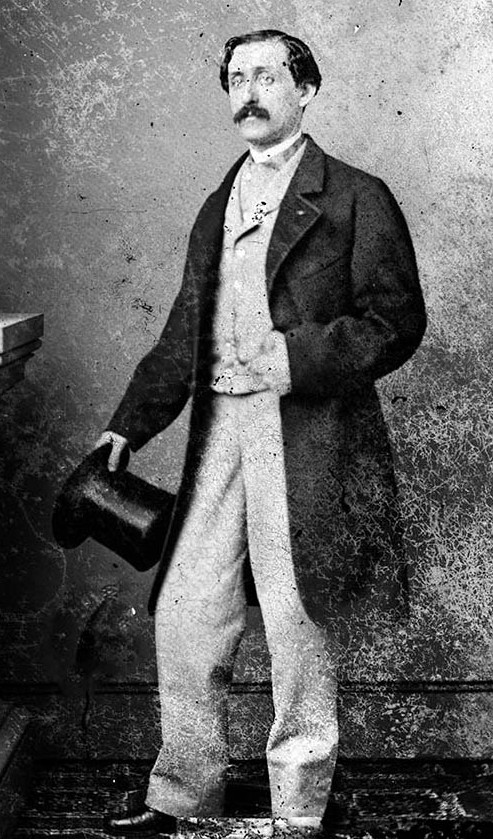

Louis Moreau Gottschalk

Often cited as the first American composer to gain international recognition, Louis Moreau Gottschalk wrote more than three hundred compositions and earned acclaim as a piano virtuoso.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Louisiana-born composer and pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk was photographed in the Washington, DC, studio of Matthew B. Brady, circa 1855 to 1865.

Though he spent much of his career outside the United States, renowned nineteenth-century composer and pianist Louis Gottschalk was born in New Orleans, and many of his compositions were inspired by the multicultural milieu of the city. Often cited as the first American composer to gain international recognition, Gottschalk wrote more than three hundred compositions and earned acclaim as a piano virtuoso. He uniquely incorporated diverse musical traditions—from African American to Caribbean, to South American—in his compositions.

Early Life and Education

Louis Moreau Gottschalk was born May 8, 1829, in New Orleans to Edward Gottschalk, a businessman of Jewish descent from London, and Aimée Bruslé, a Louisiana native of St. Dominguan descent. By 1841 it was clear that the precocious young pianist had learned all he could in New Orleans and should pursue studies in Paris. Gottschalk’s departure for Europe marked the end of his residency in New Orleans, as he would visit the city only a few weeks at a time later in life. Yet, as biographer Frederick Starr points out, Gottschalk “felt himself to be perpetually in exile from his New Orleans home, an uprooted wanderer in the best Romantic tradition.”

Arriving in France, Gottschalk tried to gain admittance to the Paris Conservatory, but because the would-be pupil was an American, the headmaster turned him away without an audition, declaring that “America is only a country of steam engines.” Gottschalk nevertheless managed to study piano with Camille Stamaty, the most sought-after teacher in Paris, and learned composition from Pierre Maledon, both of whom also taught Camille Saint-Saëns during the same period. By 1845, after entertaining many Paris aristocrats in their salons, Gottschalk gave a free concert in a public hall. Frédéric Chopin sought out the teenager backstage after the performance and said, “Give me your hand, my child; I predict that you will become the king of pianists.”

Success and Fame

Gottschalk in fact became the pianist of kings, playing for and even with members of several European royal families as he toured France, Switzerland, and Spain in the early 1850s. Journalists raved over his compositions and performances, and women pursued him. His fame as a ladies’ man reached the same level as his acclaim as an artist, and his reputation in both roles was well deserved. Gottschalk’s exit from Europe and return to his home country was reportedly necessitated by one too many entanglements with aristocratic women.

Gottschalk’s tours in the United States and the West Indies were equally popular, heralded with lavish coverage in the press that drew hundreds and even thousands to watch him play. The artist kept up a feverish pace through the 1850s, often performing two or even three concerts in a day, hobnobbing with high society, and traveling more than ten thousand miles in a single tour. Many writers compare Gottschalk’s fame and style of living to that of today’s rock stars.

After performing and writing music in Cuba and Puerto Rico, Gottschalk found his own nature harmonized well with life in the West Indies. For almost three years, he drifted from island to island, giving occasional concerts, but spending much of his time playing and composing in isolation. When he eventually began to run low on money, Gottschalk returned to the United States and resumed touring. From 1862 to 1865, while the Civil War raged, he made appearances in the northern states, traveling with two extra-long pianos he called his “mastodons.” Gottschalk even entertained his audiences with “monster” concerts featuring fantasias on themes from Giacomo Meyerbeer and Giuseppe Verdi that were played by ten pianos at a time. By the end of the war, Gottschalk was touring California when another scandal—this time involving a teenaged society girl from Oakland—forced him to board the first steamer available, which carried him to South America. Although the composer’s friends eventually cleared Gottschalk’s name, he never returned to the United States.

Significance of Works

Compared to the composers who chose to remain in New Orleans, Gottschalk falls into a category of his own. He was among the first pianists of American or European descent to attain a truly intercontinental career. Like his New Orleans counterparts, Gottschalk composed music based on popular forms, such as the polka, waltz, mazurka, and march. His technical exploitation of the piano, formidable by any standard, set him apart from his contemporaries. Gottschalk’s writing includes interlocking octaves and chords, brilliantly conceived passagework, and complex arpeggio patterns. His unique sonorities run the gamut from percussive bass effects to intricate filigrees in the highest register of the piano. He possessed sound contrapuntal and harmonic capabilities, and a vibrant rhythmic sense influenced by the music of his native Louisiana and surrounding cultures.

Like Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, Gottschalk was a pioneer in incorporating nationalistic and folkloristic elements into serious concert music. He introduced to the world the captivating rhythms of the Caribbean in “Souvenir de la Havane” and “Souvenir de Puerto Rico” and the Creole folk melody in “Bamboula” and “La Savane.” His use of the vernacular further differentiated him from other New Orleans composers, who rarely produced music in their regional dialect. Wherever Gottschalk traveled, he drew on themes native to that region; when he toured the United States, he composed a number of pieces on distinctly American themes: “Columbia: Caprice Américain,” “Home Sweet Home,” and “The Banjo.” “Union,” a dramatic paraphrase of patriotic songs, indicates Gottschalk’s political convictions concerning the American Civil War.

Critics sometimes claim that Gottschalk’s music relies too much on bombast and the more metallic tone qualities of the piano; however, his three extant ballades and a number of other lyrical pieces prove that he was capable of creating works of heartfelt intimacy. In addition to his piano pieces, Gottschalk composed songs and several orchestral and operatic works. Of these, his most successful are his descriptive symphony A Night in the Tropics and his only extant opera, Esceñas Campestres.

Early Death

In November 1869, while suffering from malaria, Gottschalk performed a series of concerts in Rio de Janeiro. While playing his favorite number, “Morte!! (She Is Dead),” he collapsed. Gottschalk did not recover and died three weeks later in Tijuca, Brazil, at the age of 40.