Latest

Review: “Krazy” by Michael Tisserand

A review of Michael Tisserand's biography of cartoonist George Herriman

Published: December 1, 2016

Last Updated: August 19, 2022

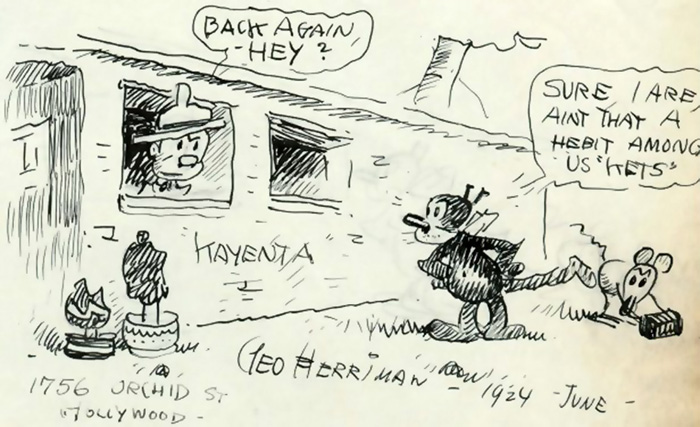

Courtesy of Michael Tisserand

Rare George Herriman drawing from the Wetherill's lodge books.

Michael Tisserand provides a painstakingly well-researched analysis of Herriman’s life and work in Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White (HarperCollins, 2016). Herriman, a man of diverse interests and experiences, created comics laden with allusions to classical literature and philosophy; written in immigrant, black and southern vernaculars; and often incorporating foreign languages. The most famous and longest-running of his comics was Krazy Kat, a gender non-conforming, color-changing cat in the southwestern desert who regularly drops philosophical gems in his own dialect of English. Literary and visual arts giants such as Amiri Baraka, e.e. cummings, Langston Hughes and Willem de Kooning lauded Herriman’s work, and his peers described him as “a cartoonist’s cartoonist.” The 1971 discovery of a New Orleans birth certificate that identified Herriman as “colored” threw fans, friends and scholars for a loop, inciting many questions, chief among them: was he of African descent, and when did he become aware of his ancestry?

Tisserand hints that Herriman did know and even that he possibly knew his whole life, but he chooses instead to focus Krazy on “how Herriman imagined himself” and if Herriman’s self-image informed the content and style of his comics, particularly Krazy Kat. With that choice, Tisserand decenters whiteness and the pseudosciences used to prop it up without pretending that they aren’t key characters in Herriman’s life, thus humanizing Herriman as a prolific though sometimes indecisive artist with deep-seated insecurities, without condemning him as a tragic mulatto.

In 1890, ten-year old Herriman, his parents, and two younger siblings climbed aboard a westbound train departing from New Orleans to the “frontier town” of Los Angeles. As Tisserand explains, the Herriman family had belonged to a class of property- and business-owning, educated, civically-engaged free people of mixed African and European ancestry. Afro-Creoles had flourished in downtown New Orleans afforded their mobility by the retention of Spanish and French colonial norms that the Anglo-Americans across Canal Street couldn’t erase after taking power following the Louisiana Purchase. After Emancipation, things shifted. Jim Crow loomed, and regardless of proximity to whiteness as signified by color, class, or education, if you were known to have any African blood, you were part of “the Negro question” – what to do with all the free Africans?

While southern and northern whites experimented with answers, New Orleans Creoles were asking questions of their own: who am I and what is my relationship to the color line? Many embraced the dichotomy and committed to using their resources to advocate for the emancipated and the manumitted alike, but others sought to determine that relationship for themselves. They struck out for new homes, places where unfamiliarity with racial mixing would allow their ambiguity to go un-othered.

Choosing the latter, the Herrimans huddled in an emigrant car bound for Los Angeles and a new life of passing.

The Herrimans did fairly well for themselves in their adopted home, Tisserand recounts. Herriman’s father, George Jr., began working at a local tailor shop and eventually bought a house, and his mother, Clara, gave birth to two more children. George thrived academically at the Catholic boys’ school he attended – taking special interest in literature and language, affinities later reflected in his comics.

By 20, Herriman had made it to New York City, although how exactly he got there would become a running joke among his friends. Herriman “knocked on the doors of the great metropolitan dailies, but they found his work too bizarre to publish.” William Randolph Hearst hired him a year after his arrival to draw for the New York Evening Journal, providing a $10 weekly salary which was raised to $15 after two months.

Tisserand writes, “From the start, Herriman’s comics jumbled high and low culture, citing Greek historian Xenophone, the Latin book Viri Romae and the Macedonian general Parmenion, as well as trafficking in stock ethnic caricatures such as Chinese launderers and coin-pinching Jews.” His editor abruptly fired him, but the professional lull didn’t last long. Cartoonists familiar with Herriman’s work recommended him for freelance gigs. His comics were well-received, but he knew that “the real ticket to success was a continuing character.” It took him 14 years to find that ticket.

Citing the memories of Herriman’s own friends, Tisserand admits that Herriman was a difficult person to get to know. The cartoonist didn’t communicate much outside of his art, perhaps because of his family secrets. His letters contain little more than pleasantries. Though he developed close relationships with his colleagues, their descriptions of him don’t seem to go beyond superficial comments on his demeanor, kinky hair, and creative genius. In Tisserand’s hands, Herriman, characterized by his inability to be characterized, is ultimately overpowered by an exhaustively detailed backdrop, a dizzying number of names and dates that make a commitment to Krazy difficult. This hardly signals a failure on Tisserand’s part – a definitive text is a hard thing to write when you’re looking to an oeuvre that spans 40 years for clues about an artist’s hidden identity.

At ten-years old, Herriman had made a life-long commitment to becoming white, a process that could never quite be completed, the consequences of which he could not have understood or predicted. Herriman’s great triumph, though, was not coming into professional and economic success on the other side of the color line or keeping his secret once he did. Herriman found and maintained his creative voice – absurd, worldly, and self-aware. A voice that, Krazy testifies, could only have come into existence as a result of the identity politics he’d had to navigate.

Lydia Y. Nichols is an essayist and arts worker from New Orleans whose south Louisiana roots predate European colonization. Often centering the cultural production of people of African and indigenous descent, her writing has been published in print in Liberator Magazine and on online arts publications Pelican Bomb and Tribes Magazine. More of Lydia’s adventures, theories, and criticisms are available on her blog, The Modern Maroon, at ModernMaroon.com.