Dew Drop Inn

From the mid-1940s through the 1960s, the Dew Drop Inn was a place where prominent African American entertainers could find work and respectable overnight lodging.

THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

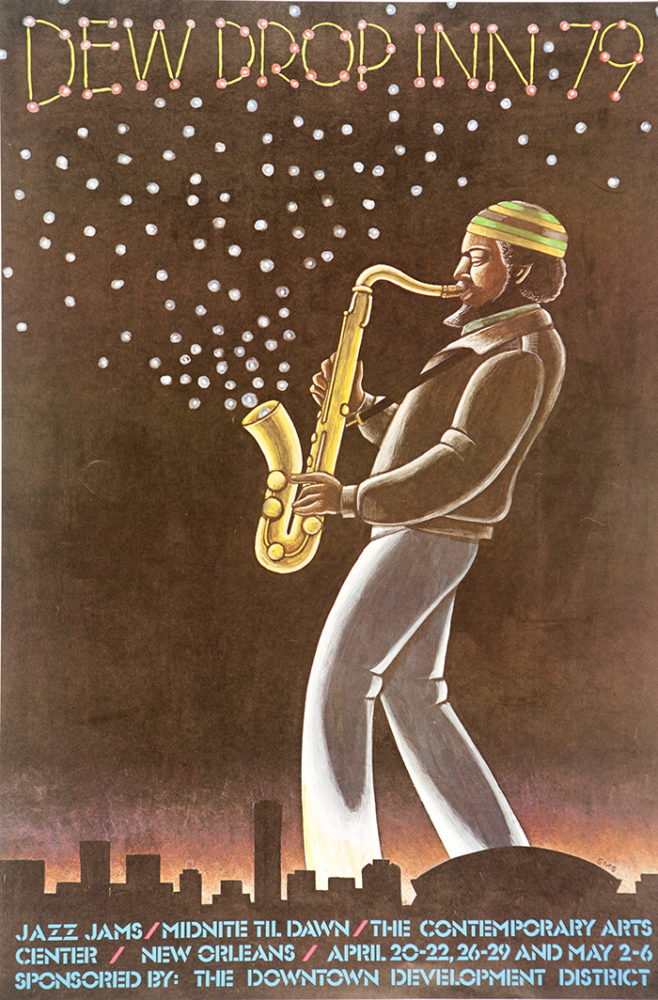

Dew Drop Inn 79.

From the mid-1940s through the close of the 1960s, one of the most popular music venues in New Orleans was a combination nightclub, hotel, restaurant, and barbershop called the Dew Drop Inn. What began as a small sandwich shop for workers from the nearby Magnolia Housing Project (officially known as the C. J. Peete Housing Project) grew into a nationally known entertainment center. Acts from all over the city and the country played the Dew Drop Inn, a star-studded roster of blues, rhythm and blues (R&B), and early rock ‘n’ roll performers that included the likes of Ray Charles, Charles Brown, Joseph “Big Joe” Turner, Solomon Burke, Bobby “Blue” Bland, William “Little Willie” John, Eskew “Esquerita” Reeder, Allen Toussaint, Shirley and Lee, Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, Earl King, Dave Bartholomew, and James Booker. Little Richard and Esquerita even wrote a song about the club called “(Meet All Your Fine Friends at) The Dew Drop Inn.”

Frank Painia, an African American barber from Plaquemines Parish, opened the Dew Drop Inn at 2836 LaSalle Street in 1939 as a hotel and added a nightclub in 1945. Painia booked the stage acts while his brother Paul ran the adjacent restaurant. Both the hotel and the nightclub filled a niche in segregated New Orleans by offering work and respectable overnight lodging to prominent African American entertainers. The music room, sometimes called The Groove Room, offered a nightly floor show that harkened back to the golden age of vaudeville. The stage featured comedians, snake dancers, magicians, drag queens, and stunt performers who chewed glass or lifted tables with their mouths.

The mistress of ceremonies for these shows was Patsy Vidalia, a well-known drag queen acclaimed for her singing and dancing. Every year Vidalia hosted the Gay Halloween Ball, by all accounts the wildest and most entertaining night of the year at the Dew Drop Inn. Drag queens in the city came in all their finery and the women bar staff dressed as men. As impresario, Painia also staged amateur nights and talent contests; after the billed acts finished, the club often hosted jam sessions that lasted until dawn or later.

“[The Dew Drop Inn] was the foundation for musicians in New Orleans,” said blues musician Joseph August, known on stage as Mr. Google Eyes. “Whether you were from out of town or from the city, your goal was the Dew Drop. If you couldn’t get a gig at the Dew Drop, you weren’t about nothing.”

The Dew Drop Inn also functioned as a community and business center. Musicians often gathered there before and after work, and Painia, who also owned a booking service, would assemble bands for gigs in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast. When musicians were stranded or out of work, the charitable Painia reportedly let them stay at his hotel and then found them a gig so they could get back on their feet and repay him. Because the Dew Drop Inn operated during segregation, law prohibited white audiences from the club. Painia not only allowed white people to frequent his establishment but also often went to jail when the police arrested his customers. The most famous raid occurred in 1952, when the police arrested Painia and actor Zachary Scott, then in New Orleans filming a movie, along with several other patrons for “mixing.”

The Dew Drop Inn operated much as it always had until 1969, when the legendary nightclub went dark. As the court system overturned segregation laws, African Americans who had been regular customers could visit venues that were previously off limits. Painia became ill in 1965; he was in and out of the hospital until his death in 1972. After Painia’s passing, the remaining businesses at the Dew Drop Inn gradually closed until the establishment only consisted of a hotel, which ultimately was shuttered as well. Repeated attempts at reviving the business in the decades since the nightclub closed have failed. In 2010, the Louisiana Landmark Society placed the Dew Drop Inn on its New Orleans’ Nine Most Endangered Sites List to draw attention to the deteriorating condition of the building, where an iconic sign still marks what was once billed as “the South’s swankiest night spot.”