Louisiana’s Secession from the Union

Louisiana seceded from the Union on January 26, 1861, although many in the state opposed the decision.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division

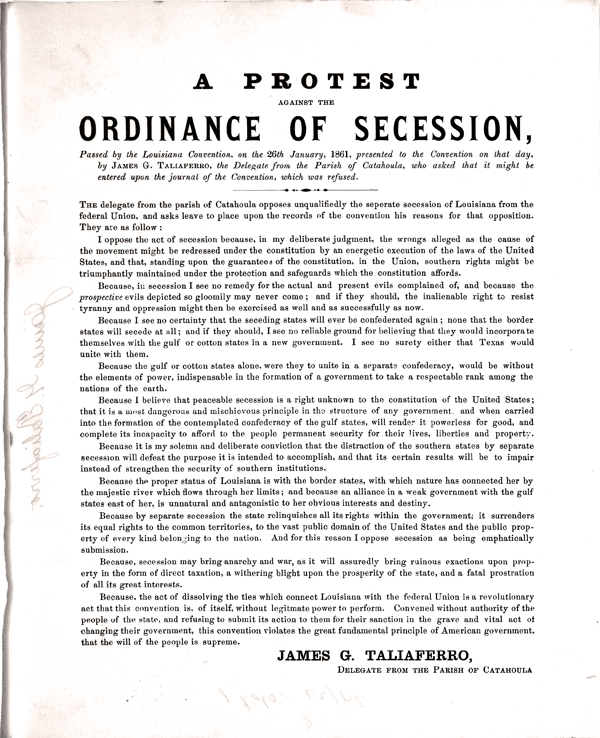

A protest against the ordinance of secession. Taliaferro, James G (Author)

On January 26, 1861, the delegates to Louisiana’s secession convention meeting in Baton Rouge voted 113 to 17 to secede from the Union. Immediately thereafter, convention president Alexandre Mouton proclaimed the connection between Louisiana and the United States to be dissolved, and in a symbolic demonstration of this change in status, the delegates lowered the American flag in the chamber and replaced it with a flag depicting a pelican feeding her young (the image on the state seal). Louisiana kept this independent status until March 21, 1861, when it transferred its allegiance to the Confederate States of America.

The overwhelming pro-secession vote at the convention undoubtedly overstates antebellum Louisianans’ commitment to secession. Throughout the prewar period, Louisiana repeatedly rejected the initiative of radical southerners who demanded that the South leave the Union. In the 1832 Nullification Crisis, Louisiana offered no support to South Carolina “fire-eaters” (fervent secessionists), and former Louisiana Senator Edward Livingston even wrote Andrew Jackson’s Force Bill, which pledged military action against those who resisted federal law. Later, the state supported the Compromise of 1850 and did not send a delegation to that year’s secessionist Nashville Convention. Also, Louisiana’s Whigs did not share the small government proclivities of their southern neighbors. Instead, they endorsed an activist nationalist government, especially regarding a sugarcane tariff and government aid to business, in a manner more akin to the northern branch of the party rather than to other southern Whigs who advocated for states’ rights.

At the same time, white Louisianans shared other southerners’ commitment both to slavery and to opposition to federal interference with the institution either in the states or territories. Consequently, the rise of a sectional Republican Party dedicated to stopping slavery’s expansion caused Louisianans to reevaluate their allegiance to the United States. In particular, two events pushed them toward secession. First, John Brown’s failed abolitionist raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859 heightened sensitivity toward both immediate threats to slavery and to the strengthening Republican Party. Second, the presidential election of 1860 dealt a further blow to the state’s conservatism. Not only did the state cast its electoral votes for John C. Breckinridge, the candidate of the southern wing of the Democratic Party, but the election resulted in the triumph of Republican Abraham Lincoln, who had not received a single popular vote in Louisiana.

The 1860 Presidential Election

Lincoln’s election changed the political calculus in Louisiana. Three weeks prior to the contest, a Democrat accurately framed Louisianans’ options in the event of Lincoln’s victory: “What are we to do? Shall we remain quiet and wait to see him inaugurated, and develop his plan and policy or shall we anticipate what it will be, and act at once to takes steps for our self-preservation? What shall these steps be? Shall we have a Southern Convention of the slave states or will each state act by itself? These are important questions.” And, for the next two months, Louisiana’s voters and political leaders struggled over the best answers to these “important questions.”

Louisiana’s political leaders, particularly Governor Thomas Overton Moore and Senator John Slidell, placed themselves in the vanguard of the state’s secession movement. Privately they maintained that they opposed immediate secession but felt obliged to follow the lead of their constituents. Nevertheless, their public actions certainly pushed their fellow Louisianans away from the Union. In particular, Governor Moore’s pro-secession speech at the opening of the special December legislative session set the mood for the election of convention delegates on January 7, 1861. Other events contributed to the secessionist atmosphere in Louisiana. In November, Benjamin Palmer, a leading Presbyterian minister in New Orleans, delivered a sermon declaring divine sanction for secession. Many newspapers reprinted the sermon, and more than fifty thousand copies were distributed. Additionally, by the time Louisianans voted in early January, South Carolina had seceded, and four other southern states had elected pro-secession conventions.

The Secession Convention

Candidates for the secession convention did not run as party nominees but instead divided between secessionists and cooperationists. The former group endorsed secession, while the latter group included some unionists but mainly comprised those who wanted to have a conference of southern states prior to any state’s secession. Secessionists captured the majority of seats. While exact results are impossible to obtain, the best estimates indicate that eighty delegates should be labeled secessionists in contrast to forty-four cooperationists and six unknown. The overall vote totals point to a less decisive victory. The official state returns, which were not released for more than a century, list secessionist delegates as capturing 52.7 percent of the vote. Part of the discrepancy between this voting percentage and the number of secessionist delegates stems from the fact that in many areas delegates ran uncontested, thus reducing voters’ desire to cast a ballot. In fact, more than 12,000 men who had voted in the November presidential election (approximately one in four of those who had cast ballots) declined to vote in January.

By the time the convention met in Baton Rouge on January 23, the result was not in doubt. Governor Moore had already ordered the seizure of the federal arsenal at Baton Rouge as well as Fort St. Philip and Fort Jackson on the Mississippi River. Additionally, with four other states—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi—having joined South Carolina outside the Union, the meaning of “cooperation” was less clear. Some delegates maintained that cooperating with their fellow southern states now meant leaving rather than remaining in the Union. The overwhelming failure of a call to send delegates to a southern convention in Nashville (24 in favor and 106 against) illustrates this decline in anti-secessionist sentiment.

After voting 113 to 17 in favor of secession on the third day of the convention, the delegates strove to maintain all appearances of unity. All but seven members signed the secession ordinance, and the delegates reacted swiftly and decisively when James G. Taliaferro, a Catahoula Parish delegate and one of the convention’s most ardent unionists, lodged a protest against secession contending that it presaged anarchy and war. Not only did the convention repudiate his protest, but the members even refused to include it in the official journal. Additionally, the delegates decided against popular ratification of secession by 84 to 45, contending that voters had already had their say when they elected the delegates. They also refused to release the official vote totals from the January 7 election of delegates, perhaps worried that publishing data that indicated 47.3 percent of the state’s voters had supported cooperationist candidates would undermine their cause.

In the wake of the convention’s vote, the state prepared for war. Volunteer units quickly sprang up. Additionally, partially in an effort to protect its western boundary, Louisiana sent an envoy to Texas to persuade the Lone Star State to join its sister slaveholding states outside the Union. The convention itself briefly adjourned to move from Baton Rouge to New Orleans in order to allow the state legislature to meet at the capitol. After the members arrived in their new location, they sent six delegates to the Montgomery, Alabama, convention that formed the Confederacy, seized the US Mint in New Orleans, and ratified the Confederate constitution on March 21 before adjourning on March 26.