George Ralston Crawford

Though he never lived in Louisiana on a permanent basis, twentieth-century painter and photographer Ralston Crawford visited New Orleans frequently and featured the city in much of his work.

Courtesy of State Library of Louisiana

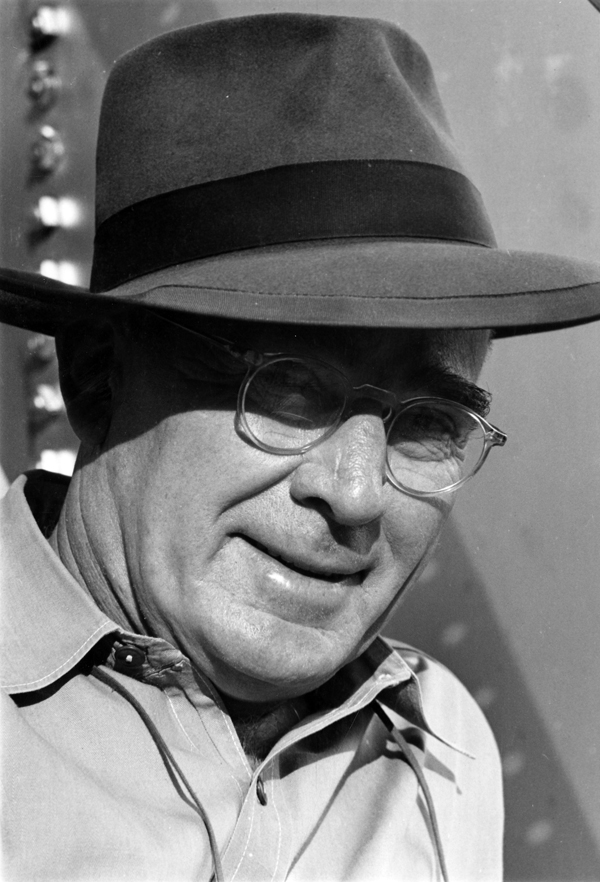

Portrait of Elemore Morgan, Sr. Ralston Crawford (Photographer)

Though he never lived in Louisiana on a permanent basis, twentieth-century painter and photographer Ralston Crawford visited New Orleans frequently and featured the city in much of his work. He was also on the faculty of Louisiana State University, and several exhibitions of his artwork took place in New Orleans and Baton Rouge. A proponent of precisionist theory in painting, Crawford’s compositions often featured crisply rendered geometric forms, abstractions of his real-world subjects. In Louisiana, he is best known for his photographs of New Orleans jazz musicians and the city’s distinctive aboveground cemeteries.

Early Life and Career

Born September 25, 1906, in St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada, George Ralston Crawford was the son of George Burson Crawford and Lucy Colvin. Crawford’s youth was spent in Buffalo, New York, where his aptitude for art propelled him to further study, first at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, California, and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. His father’s early career as a Great Lakes ship captain, and Crawford’s own six-month stint aboard the United Fruit Company’s La Perla, exposed him to imagery that would recur in paintings, prints, and photographs throughout his career. The influence of the sea and ships on Crawford’s life and work is difficult to overstate.

After his studies, Crawford resided in New York City. In 1932, he married sculptor and poet Margaret Stone and took a six-month honeymoon to Europe, spent mostly in Paris, that furthered his artistic education. The Crawfords returned to New York during the Great Depression, when he was briefly employed by the Public Works of Art Project, an agency of the New Deal. During this period, Crawford dabbled in the artistic politics of the Left, contributing articles to The New Hope. He identified with many unemployed (or underemployed) artists, and joined the American Artists Congress.

In 1935, the family (there were two children now) moved to Exton, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia. Gallery representation soon followed (at the Mellon Gallery, directed by Philip Boyer), and Crawford’s paintings began to garner critical acclaim. The late 1930s marked the development of Crawford’s identifiable and mature style—abstracted, recognizable subject. The graphic economy of this style of painting and printmaking places him firmly in the American art movement called precisionist (other adherents include Charles Scheeler and Stuart Davis, who were Crawford’s seniors by a generation), and it was a style, a credo, that he never fully abandoned when using those techniques. “A painting is a thing seen. It is not something to be read,” he wrote in a 1939 letter. Though arguably more abstracted and drawing upon multiple episodes forged in a single work, his later works were always grounded in observation rather than invention.

During World War II, Crawford had an assignment as a U. S. Navy photographer, but was rejected after failing the physical. As a result, he worked stateside as an illustrator in various military agencies. Just prior to the signing of the armistice with Japan, he was sent to India and later to the Bikini Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean, where he witnessed an atom bomb test and created a series of paintings based on that experience.

Career in Louisiana

Crawford’s work as a photographer sometimes deviates from the linear and flat sparseness of his painting and graphic style. This is especially true of his photographs that limn the contours of the world of New Orleans jazz during the mid-twentieth century. What art historian Barbara Haskell has termed “the calm monumentality” of Crawford’s paintings is at odds with the closely observed energy, even visual chaos, of New Orleans musicians and their environments.

Crawford began visiting the city in 1938 and continued until the time of his death forty years later. The bulk of his photography in New Orleans occurred between 1949 (when he was a member of the art faculty at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge) and his death in 1978. The series consists of many thousands of negatives and prints, hundreds of the latter now housed in Tulane University’s William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz. Unlike painting, which offered the ability to synthesize a perfect (if nonexistent) moment, Crawford saw his jazz photographs as letting truth unfold frame by frame. There is no visual evidence that he ever used these subjects as the basis for prints or paintings.

Another New Orleans subject recorded in photographs—the city’s cemeteries—proved different. The brilliant light (and consequently inky shadows) of these environments produced photographs of bold graphic form, aligned much more closely with Crawford’s approach to painting and printmaking. Direct relationships between some of these images are readily observed.

An exhibition of paintings, prints, and photographs at Louisiana State University in 1950 marks his first one-person show in the Pelican State. The January 1952 issue of the French magazine, Le Jazz Hot, appears to be the first publication of his New Orleans jazz photographs. The Bienville Gallery in New Orleans had major exhibitions of his work in 1969, 1973, and 1976. An exhibition of his New Orleans photographs was held at The Historic New Orleans Collection in 1983. The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City presented a retrospective exhibition of his work in 1985.

When in London in 1971, Crawford discovered that he had terminal form leukemia. On April 27, 1978, he died in Houston, Texas. His will, penned more than two decades earlier, specified a brass band or jazz funeral in New Orleans. Even the musicians he wanted to play were specified. Interment was in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3.