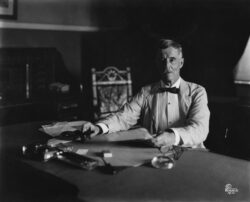

John Parker

John M. Parker, who served as governor of Louisiana between 1920 and 1924, was a passionate advocate of political reform movements and good government initiatives.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

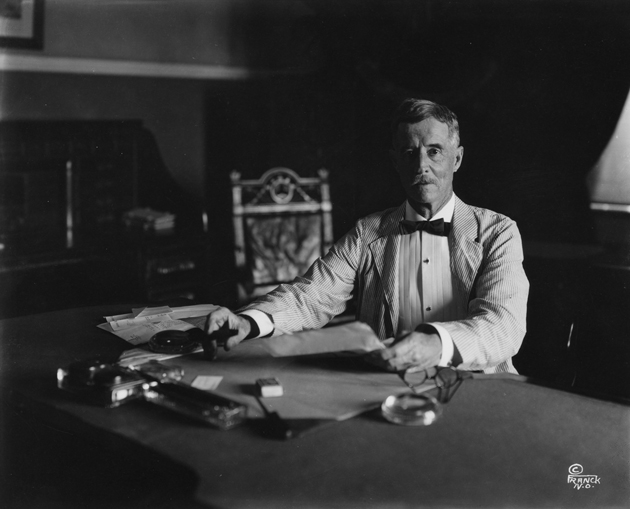

Governor John Parker. Charles L. Franck Photographers

John M. Parker, who served as governor of Louisiana between 1920 and 1924, was a passionate advocate of political reform movements and good government initiatives.While the Parker administration was controversial, it helped bring about a reordering of Louisiana politics, shifting what had traditionally been a conflict between machine v. anti-machine forces to a more complex interplay among conservative, liberal, populist, and progressive forces. Although he was elected governor with the support of Huey P. Long, the two eventually became bitter enemies and it is perhaps his anti-Longism for which Parker is best remembered.

Born in Bethel Church, Mississippi, on March 16, 1863, John Milliken Parker was the son of John Milliken Parker and Roberta Buckner Parker, both of whom came from prestigious families with large landholdings in Mississippi. The family moved to New Orleans in 1871 where the senior Parker worked as a cotton factor. Suffering from poor health as a youth, the younger Parker attended private schools including Chamberlain Hunt Academy at Port Gibson, Mississippi; Belle View Academy in Virginia; and Eastman’s Business School in Poughkeepsie, New York. After working on a family plantation, Parker formed Parker-Hayes, Co., a wholesale grocery business, in 1884. In 1888 he married Cecille Airey, with whom he had four children.

By the late 1890s John Parker was described as one of the wealthiest businessmen and planters in the South and was a prominent spokesman for various commercial and agricultural interests. He was, for example, the youngest president in the history of the New Orleans Cotton Exchange and the New Orleans Board of Trade. Later he organized the Southern Commercial Congress and served as its first president. Politically, Parker became known as an opponent of both the Louisiana Lottery and the Regular Democratic Organization (also known as the “Old Regulars,” “The Machine,” or “The Ring”), an allegedly corrupt political coalition led by New Orleans mayor Martin Behrman.

In 1910 Parker, then the leader of the Good Government League, persuaded Luther E. Hall to run for governor. Hall, however, failed to achieve the level of reform that Parker and others expected. In 1912 Parker joined the national Progressive Party formed by former President Theodore Roosevelt, Parker’s personal friend and hunting companion. Though Parker espoused causes associated with Progressivism, including women’s suffrage, the abolition of child labor, income and inheritance taxes, and conservation, his progressivism did not extend to the state’s African American residents. In fact, Parker was instrumental in excluding blacks from the southern branch of the Progressive Party.

In 1916, no longer content to campaign for others, Parker ran for governor of Louisiana as the Progressive Party candidate, though he lost to Democrat Ruffin Pleasant. After serving as the Louisiana Food Administrator during World War I, Parker again ran for the governorship, this time successfully defeating Colonel Frank P. Stubbs of Monroe.

As governor, Parker focused his efforts on eliminating corruption within the state, but particularly in New Orleans. It was partly through Parker’s efforts that Behrman was defeated in the 1920 mayoral election. He also fought the Ku Klux Klan and promoted the Constitution of 1921, which helped modernize state services and provide additional revenues.

During Parker’s administration appropriations for state institutions increased from $12.3 million to $28.1 million. Particularly significant improvements were made in the treatment of the mentally ill, as many patients were transferred from state prisons to charity hospital facilities. Reaching “gentlemen’s agreements” with industry leaders, Parker introduced or raised severance taxes on natural resources and increased the regulatory powers of the Public Service Commission. Critics later charged, however, that his efforts amounted to pandering to corporate interests.

Though Huey P. Long campaigned for Parker in 1920, he later opposed Parker’s reform agenda, refashioning many of his ideas in a more popular and, from Parker’s viewpoint, radical and irresponsible form. After leaving office, Parker became increasingly involved in anti-Longism. He also devoted himself to his experimental farm at Bayou Sara near St. Francisville and directed relief efforts during the Flood of 1927. He died at Pass Christian, Mississippi, on May 20, 1939 and is interred in Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans.

Adapted from Matthew J. Schott’s entry for the Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, a publication of the Louisiana Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette.

Sources: Matthew J. Schott, “John M. Parker of Louisiana and the Varieties of American Progressivism” (Ph. D. dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 1969); Spencer Phillips, “Administration of Governor Parker” (M.A. thesis, Louisiana State University, 1933); New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 18, 1924, obituary, May 21, 1939; papers, University of North Carolina; papers, University of Southwestern Louisiana.