Sicilian Lynchings in New Orleans

After the murder of New Orleans police chief David Hennessy in 1890, political conflict between reformers and ward bosses resulted in mob violence and lynching, and eleven Sicilians were killed.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

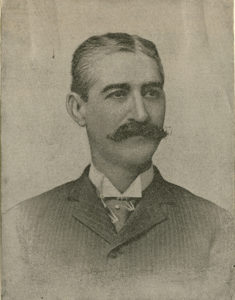

This photographic halftone is a portrait of New Orleans superintendent of police David Hennessy, who was murdered on October 15, 1890.

Perhaps no event better encapsulated the political and social struggles of late nineteenth-century New Orleans than the controversy surrounding the murder of police chief David C. Hennessy and the retaliatory lynching of Sicilians that followed. This act of vigilante violence became known as the “Who killa da chief?” scandal, phrased in a mockery of Italian American dialect. Far more than simply a matter of law and order, it was a reflection of both the era’s urban machine politics and the fear that New Orleanians had of foreign newcomers during an era of mass immigration. Moreover, it revealed the troublingly thin lines separating individuals involved in law enforcement, politics, and organized crime.

Factional Politics in New Orleans

Hennessy was the son of Irish immigrants who had come to New Orleans during the potato famine of the 1840s. During the Civil War, Hennessy’s father enlisted in the Unionist First Louisiana Cavalry and served under the command of Algernon Sydney Badger, establishing a bond that shaped the futures of both father and son. When Badger became the commander of the Republican Metropolitan Police after the war, the elder Hennessy was hired to the force and worked as a patrolman until he was gunned down in a barroom in 1869. Though only a boy of eleven, the younger Hennessy began working as a messenger for the Metropolitans after his father’s death and went on to pursue a career in police work.

Following the Compromise of 1877, Louisiana’s Democratic Party ousted the Reconstruction-era government in a factional struggle for political control of New Orleans that had a profound influence on Hennessy’s career as a lawman—and ultimately would prove a factor in his death. The coalition of Democrats who had joined together to overthrow Republican rule had split into competing camps. On one hand stood the Regular Democratic “Ring,” an urban political machine with roots stretching back to the city’s antebellum period. Statewide, the Ring allied with planters from Louisiana’s cotton parishes and, in New Orleans, found its base among the city’s various immigrant groups as well as francophone Creoles. By 1880, the German and Irish ward bosses who had controlled the Ring for decades were joined by an increasing tide of Sicilian immigrants who were becoming the dominant ethnic group working on the Mississippi River wharves and in the French Quarter. The Ring faced opposition in New Orleans from a group who styled themselves as “Reform Democrats” or “Reformers.” Elite professionals and merchants provided youthful leadership for the Reform movement, but it also included its share of immigrants, many of whom harbored rivalries with their countrymen in the Ring. Though no longer in power, Republicans still constituted an important segment of the electorate, and in most cases they could be counted on to support the Reformers and the aims of their political club, the Young Men’s Democratic Association (YMDA).

As a lawman with career ambitions in New Orleans, Hennessy had little choice but to cast his lot with one of these two factions, and more often than not he sided with the Reformers and the YMDA. Hennessy’s allegiances had implications on the job, for jealous rivals sought to rid themselves of such a competent adversary, and it was the Ring that dominated city politics in the 1880s. Thus, Hennessy’s enemies came not only from the city’s criminal element but also from within its divided police force. As a consequence, when the young detective first came to national fame after helping to apprehend a notorious Italian mafioso by the name of Giuseppe Esposito in 1881, he had done so purposefully—without the knowledge of his superior, Chief of Detectives Thomas Devereaux, a Ring operative. Hennessy’s actions drew the ire of Devereaux, who charged David and his cousin, Mike Hennessy, with being absent from their posts. The Hennessys were cleared of any wrongdoing, but not long after, they met Devereaux in a gun battle in the street; Devereaux seriously injured Mike Hennessy and, in turn, was killed by David. Though acquitted of murder on a claim of self-defense, David Hennessy had to leave the force temporarily, finding work as a private detective and security man.

During this period away from the police force, Hennessy formed a relationship with the Provenzano family, one of the two key factions among the Sicilians who controlled the unloading of fruit cargoes along the river. In the mid-1880s a rival family, the Matrangas, had managed to muscle in on what had been a Provenzano monopoly in the fruit business. Moreover, the capture and deportation of Esposito, the Italian crime boss, had created a rift among the Sicilians of New Orleans, with the Matrangas taking a lead role in rallying support for his legal defense. By the mid-1880s, a series of violent confrontations between the two families had left an unknown number dead. Despite having deep ties to the immigrant-dominated Ring, the Provenzanos seem to have sought out friends among influential figures in the YMDA faction, including Hennessy. His conspicuous role in the arrest and deportation of Esposito, along with his relationship with the Provenzanos, offer some of the strongest evidence for Matranga involvement in his later assassination.

Hennessy Appointed Chief of Police

When Reformer and YMDA man Joseph Shakspeare won the mayor’s office from the Ring in 1889, he appointed David Hennessy as chief of police. Believing that it had finally gained the upper hand in city politics, the YMDA under Shakspeare decided to make a more thorough swipe at the foundations of the Ring’s financial and patronage power. The first task that the mayor assigned to Hennessy was the consolidation of the police force. Under the Ring, the police department had been divided into two autonomous branches—one of detectives and one of patrolmen. The reordering caused many political appointees to lose their jobs. Some of these men were violent individuals—political enforcers with a badge and gun, and lawmen in name only. At the same time, the mayor enacted the “Shakspeare Plan” in an attempt to regulate and collect revenue on the ostensibly illegal vice trade in New Orleans. Brothel and casino operators had paid protection money to policemen under the Ring’s rule, but now the “Reformer” Shakspeare wanted all funds to flow directly into his office in exchange for unofficial sanction. Mayor Shakspeare placed Hennessy in charge of collecting these taxes. Thus, the new chief was unpopular not only with the Matrangas but also with many current and former policemen as well as the city’s vice-den operators.

The Matranga Investigation

In the months leading up to his death, Chief Hennessy had been investigating the activities of the Matranga family and, in particular, the actions of Joseph P. Macheca, considered the wealthiest Italian businessman in New Orleans. Hennessy and his YMDA superiors sought to clamp down on the Mafia societies and their activities, and they suspected that Macheca played a leading role in directing their criminal schemes. Macheca had built up a successful shipping company and imported a significant amount of produce from Honduras. He had been influential in Ring politics since the start of Reconstruction, and his band of workers, known as the Innocenti, had been conspicuous in that era’s street fighting, including alongside the White League during the Battle of Liberty Place. When Macheca shifted his business away from the Provenzano family to the Matrangas in the mid-1880s, his action fostered discord along the docks and attracted the attention of the press and law enforcement. It is possible that Hennessy believed that the Provenzanos had come to him seeking to help the city’s law-abiding citizens drive out the Mafia influence that many New Orleanians believed now ruled the French Quarter. Yet it is also likely that the Provenzanos were using Hennessy for their own purposes, and historians may never know whether the chief was complicit in the plans to strike at the Matranga rivals. At the time of Hennessy’s death, several members of the Provenzano family stood trial for a violent May 1890 attack against some Matranga stevedores. Hennessy, probably realizing too late that he could not trust the Provenzanos, was murdered a few days before he was to testify on their behalf.

Mob Violence and Public Lynchings

On the night of October 15, 1890, a group of unknown assailants wielding shotguns cut down Hennessy as he headed down Basin Street to his Girod Street home. Returning fire but failing to strike any of his attackers, the chief of police collapsed in the street. Alerted by the sound of gunfire, friends ran to his aid. When they asked the badly wounded Hennessy who had attacked him, legend has it that he said, “dagoes.” Hennessy died the next day.

As Hennessy lay dying, an outraged Mayor Shakspeare called on a “Committee of Fifty” to address the growing crisis that the chief’s assassination had precipitated. For the preceding decade, Americans had read alarming newspaper accounts of a growing threat from Italian Mafia societies, and now the police chief of a major city was presumed to have been assassinated by such an organization. The newspapers in New Orleans were awash with editorials calling for mob justice against the assumed attackers. Police began rounding up Italians whom they suspected of knowing anything about the attack, including such prominent men as Joseph P. Macheca and Charles Matranga. In total, the police investigating Hennessy’s slaying arrested nineteen men, all of whom were Italian.

The Trial

The first nine of these defendants, charged with direct involvement with the murder, went to trial in mid-February 1891. Although the men had been portrayed in the city’s newspapers as guilty long before the trial ever started, defense attorneys under the lead of Ring lawyer Lionel Adams was able to establish alibis for all of the men on trial, and the jury acquitted six of the men and deadlocked on the remaining three. News of this outcome electrified opinion within the city and reinforced the widely held belief that the Mafia had successfully subverted justice either by bribing or intimidating the jurors. As a consequence, the Committee of Fifty called for a mass meeting of “the people” for the next day, March 14, 1891.

The Mass Meeting and Lynching

A crowd assembled the next morning around the Henry Clay statue, which at the time stood in the middle of Canal Street at the intersection of Royal Street and St. Charles Avenue. Reformer elites John C. Wickliffe, Walter Denegre, and William S. Parkerson gave inflammatory speeches to the crowd, working their listeners into a lather over what most believed to be the corruption of Mafia societies and the threat they posed to order. All three men had strong ties to the YMDA, with the thirty-year-old Parkerson having recently managed Shakspeare’s mayoral campaign. Thus, the throng that set out from the assembly not only harbored strong antipathy for Italians but also was influenced by a strong political subtext. Moreover, though it was an unruly mob, the fact that its leadership enjoyed close ties to the Shakspeare administration lent an air of official sanction to their deeds.

Although the Sicilians had been acquitted of Hennessy’s murder, police had returned them to the parish prison on Marais Street (the site is now part of Armstrong Park) because they all had other outstanding charges against them. The mob encountered little resistance from the police guarding the prison and stormed inside to hunt down the inmates. Gun-wielding vigilantes shot down nine of the Sicilians inside the jail, including the shipping magnate J. P. Macheca. The pack dragged two more men outside, where the crowd hanged them from lampposts. Despite all of this violence, two of the more conspicuous men among the prisoners, Charles Matranga and Bastiano Incardona, went unharmed. Widely regarded as ringleaders of the French Quarter Mafia alongside Macheca, their survival left open-ended questions as to the true motivations behind the lynching. While Mayor Shakspeare did not take responsibility for the day’s events, neither did he regret them.

The lynching of Sicilians in the wake of the Hennessy murder was not an isolated incident, as Italians across the Gulf South fell victim to mob violence throughout the 1890s. Yet just as it was in the Hennessy lynching, motivating factors other than ethnic hatred fed such violence. It took place in an era of political violence and coincided with a demographic shift that brought thousands of Sicilian immigrants to the region. Yet perhaps it is most important to note that while the YMDA sought to deliver a mortal blow to the Ring in New Orleans and intimidate Sicilian immigrants into meek submission, it accomplished neither. Machine politics rebounded as early as 1896, and New Orleanians of Italian descent assumed an integral role in the civic, economic, and political life of the city.