Lee Dorsey

Vocalist Lee Dorsey recorded some of the biggest rhythm and blues hits of the 1960s.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

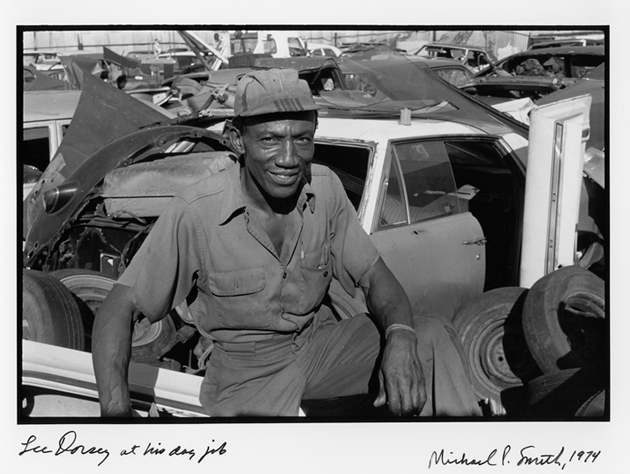

Lee Dorsey in junk yard. Smith, Michael P. (Photographer)

Vocalist Lee Dorsey recorded some of the biggest rhythm and blues (R&B) hits of the 1960s, most of them in collaboration with pianist/vocalist/songwriter/arranger Allen Toussaint. His personable charm and easygoing delivery, combined with Toussaint’s catchy and funky songs and arrangements, produced a series of instantly memorable hits such as “Ya Ya,” “Working in the Coal Mine,” and “Ride Your Pony.” Although he was not a technically gifted singer, Dorsey’s warm, engaging vocals suited his songs perfectly; as Toussaint commented, “His voice was like a smile.” Dorsey’s songs mark the transition from 1950s New Orleans R&B to the 1960s funk sound of The Meters.

Early Life

Born Irving Lee Dorsey on December 24, 1924 (some sources say 1926) in New Orleans, Dorsey and his family moved to Portland, Oregon, when he was ten years old. While serving on a US Navy destroyer during World War II (1939–1945), Dorsey was injured when a Japanese fighter plane attacked his ship. After leaving the military, Dorsey began a career as a lightweight/featherweight boxer nicknamed “Kid Chocolate,” who remained undefeated when he retired from the sport in 1955. That same year he returned to New Orleans and learned auto body repair with funding provided by the G.I. Bill.

In 1957, Dorsey was working at a body shop owned by local DJ “Ernie the Whip” when talent scout Reynauld Richard heard him singing and invited Dorsey to Cosimo Matassa’s recording studio that evening. The result was Dorsey’s first single, “Rock Pretty Baby,” released on the Rex label. The single was successful enough to earn Dorsey a trip back to the studio to record “Lottie Mo” for local producer Joe Banashak’s Instant label. The record featured a young Allen Toussaint on piano; it was an association that would prove fruitful for both men. The recording was later leased to Ace Records and appeared on its Valiant subsidiary in 1959. The song’s popularity in Mississippi and Louisiana led to another lease, this time to ABC-Paramount, in the hopes of achieving national popularity.

Though the record was not a national hit, “Lottie Mo” came to the attention of promoter Marshall Sehorn, then working for Fire/Fury Records in New York City. When Sehorn realized Dorsey was not under contract, he instructed Bobby Robinson, head of the label, to check out the singer. Robinson traveled to New Orleans and met with Dorsey; but, though he liked the singer’s voice, they had no material to record. While sitting in Dorsey’s living room, however, the pair heard some children outside reciting a ribald chant: “Sittin’ on the slop jar, waitin’ for my bowels to move.” After retiring to a local bar, they removed the scatological elements from the rhyme and added lyrics of their own to create the nonsense song “Ya Ya.” Though Toussaint’s contract with Minit Records prevented him from playing on the recording, pianist Marcel Richardson imitated Toussaint’s style perfectly. “Ya Ya” went to #1 on the R&B charts and #7 on the pop charts in 1961. A slightly altered version by British singer Petula Clark, “Ya Ya Twist,” became an international hit about a year later.

Career Development

Dorsey followed “Ya Ya” with the minor hit “Do-Re-Mi” in 1962, written by guitarist Earl King. Though he toured extensively, opening for artists such as Big Joe Turner, Chuck Berry, T-Bone Walker, and James Brown, and appeared on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, Dorsey was unable to duplicate the success of “Ya Ya.” With a large family to support, he returned to auto body repair, occasionally singing in local clubs in the evenings. He recorded a handful of additional singles during the period between 1962 and 1964 for Fury and other labels, but with no success.

Toussaint, meanwhile, had entered the US Army in 1963. Upon his discharge in 1965, Marshall Sehorn invited Toussaint to record a four-song session with Dorsey, hoping to revitalize Dorsey’s career. “Ride Your Pony,” which featured gunshot sound effects (likely influenced by Junior Walker’s hit “Shotgun” from just a few months earlier), reached #7 on the R&B charts and #28 on the pop charts in 1965.

The year 1966 marked the peak of Dorsey’s success. Three singles from that year, “Get Out of My Life, Woman,” “Working in the Coal Mine,” and “Holy Cow” all made the R&B Top Ten list, though it was “Working in the Coal Mine,” with its clanking sound effects and Dorsey’s comic complaints about his job, that became his signature song. Although his later hits also charted, they did not achieve the same level of success. The legendary instrumental funk group The Meters served as the backing band on Dorsey’s 1969 hit “Everything I Do Gonh Be Funky (From Now On)” and on many other subsequent recordings.

Dorsey’s 1970 Polydor album Yes We Can featured a track that later became a major hit for the Pointer Sisters under the title “Yes We Can Can.” His 1978 comeback attempt Night People, on the ABC label, garnered positive reviews, and other artists covered a few of its tracks, yet it failed to sell. Dorsey also appeared as a guest artist on Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes’s 1976 debut LP; and, in one of the more unusual concert pairings, opened for British punk group The Clash on their 1980 tour. He also made several appearances at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival during the 1970s and 1980s.

Later Career

Dorsey’s happy, joyous music sounds as fresh today as when it was recorded, and his songs have been covered by a lengthy list of artists including Robert Palmer, John Lennon, Ike and Tina Turner, The Judds, Buckwheat Zydeco, Little Feat, The Band, Ringo Starr, Linda Ronstadt, Harry Connick Jr., Steve Miller, Booker T. and the M.G.s, Tommy James and the Shondells, Rufus Thomas, and many more. Even New Wave rockers Devo enjoyed a hit with their 1981 version of “Working in the Coal Mine.” Dorsey’s songs have also been frequently sampled by hip hop and alternative rock artists such as Beck, De La Soul, Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, and others.

In his personal life, Dorsey fathered at least eleven children (some sources say as many as thirty-two) with different mothers. By all accounts, he was as personable, amiable, and down-to-earth as his records sound. A lifelong smoker (his condition may have been worsened by the paint fumes at his workplace), Dorsey developed emphysema and died in New Orleans on December 2, 1986. He was buried at Restlawn Memorial Park in Gretna. Dorsey’s regular-guy approach to stardom and life is perhaps best summed up by his own comment, “I never knew if I was a better body-and-fender man or a vocalist.”