George Dureau

George Dureau, a quintessential New Orleans artist, also is a nationally recognized painter, sculptor, and photographer.

Courtesy of Ogden Museum of Southern Art

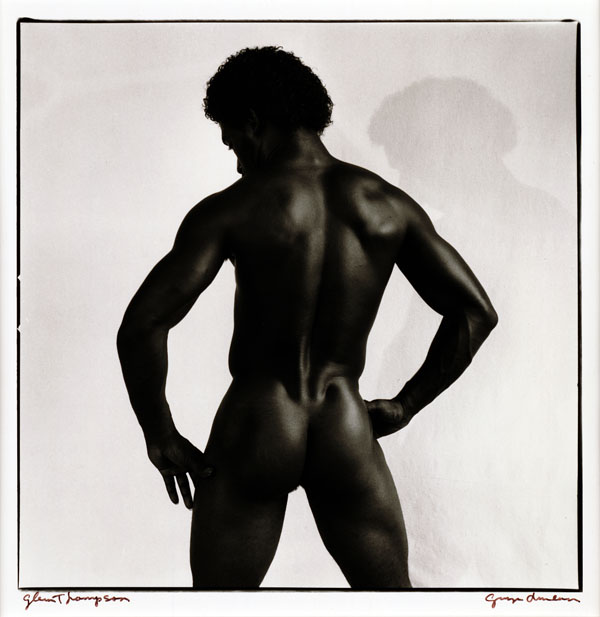

Glen Thompson. Dureau, George (Artist)

George Dureau, a quintessential New Orleans artist, also is a regionally and nationally recognized painter, sculptor, and photographer. He is recognized for his focus on the human figure, often the male nude, presented in paintings, drawings, and charcoal sketches alluding to classical art forms, especially Renaissance and Baroque art, such as Three Maenads and a Centaur (1997). Dureau’s photographs of nudes, street people, and the maimed and deformed have also brought acclaim.

Born and raised in New Orleans, Dureau has maintained his studio and residence in the French Quarter for decades. In 1991, Terrington Calas reviewed Dureau’s works and offered this conclusion: “Dureau has never been a painter of ordinary ambition, and the elevated heroic sense that he essays—and usually masters—in these new canvases, is a testament to a sheer greatness of vision.” Calas also observed that Dureau “submits the human figure with a mythic, rhetorical heroicism that conjures the vaulted saints and sinners of late Renaissance art. What’s more, his figures occupy the sort of waveringly lighted, spectral, and dramatic space that was an earmark of the Baroque.” In 1999, critic Doug MacCash described Dureau’s artistic stature as the twentieth century was coming to an end: “Over his 35-year career, his sinewy drawings, paintings, and occasional sculptures have made him the perennial darling of the New Orleans art scene. More than any other artist in memory, he has enjoyed wide popular acclaim while continuing to be taken seriously by the critics, curators, and collectors of the local art establishment.” In October 2011, in recognition of his contributions to the art and culture of New Orleans and the larger South, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans presented Dureau its highest honor, the Opus Award.

Beyond New Orleans, however, Dureau’s reputation as a photographer is more prominent than his reputation as a painter. Edward Lucie Smith, writing about Dureau’s photography in 1983, noted that “it is probable that many more people know his photographs than are familiar with his paintings and drawings,” due, in part, to the fact that “Dureau’s striking work in the medium appears in an increasing number of books and magazines.” Smith also described his primary photographic subjects as “heads, single figures, and small groups. The figures are male or female nudes, New Orleans street people, and very often cripples, and people deformed at birth, or maimed in some accident.” Smith also pointed to a central factor in Dureau’s works, that being “our sense that the photographer and his subjects have entered into a shared enterprise, whose purpose is to record not only outward appearances, but an inner sense of worth in the person being photographed.” A related and unifying element in Dureau’s paintings and photographs is his use of a group of male models including Troy Brown, B.J. Robinson, Glenn Thompson, Terrell Hopkins, and Earl Levell.

George Valentine Dureau was born in the Bayou St. John neighborhood of New Orleans on December 28, 1930, and was raised in an extended New Orleans family. While he was growing up, he became immersed in New Orleans’s unique culture, including the celebration of Mardi Gras and the history of its diverse neighborhoods. An aunt gave him early art lessons, and he also enrolled in art classes at the Delgado Museum of Art (now the New Orleans Museum of Art). After he served in the military during World War II, Dureau returned to Louisiana and attended Louisiana State University from 1946 to 1952, where he studied with Caroline Durieux and other Louisiana artists. After studying architecture at Tulane University in1952, Dureau began to work as an advertising and display manager for downtown department stores, enjoying his impact upon the visual aesthetics of Canal Street and its store windows, until he was able to support himself as a full-time artist, beginning around 1960.

Dureau became affiliated with the Downtown Gallery in New Orleans, presenting a series of exhibitions there during the 1960s. He was given his first art exhibition at the Delgado Museum of Art in 1965. In 1977, a retrospective exhibition, George Dureau: Selected Works, 1960–1977, was presented at the Contemporary Art Center. During the 1980s and 1990s he was included in many museum and gallery exhibitions, both nationally and internationally. By the late 1980s, Dureau was affiliated with the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans, and exhibited there on a regular basis. During these years his works demonstrated his increasing preference for classical nude figures and a related range of classical themes and subjects, as evident in a painting such as Scandal at the Forge of Vulcan Café (1997).

During the 1990s, Dureau acquired two significant and prominent public art commissions in New Orleans, both sculptural. First, working in partnership with Ersy Schwartz, he created the bronze and steel Gates to the North Courtfor the expansion of the New Orleans Museum of Art (1993). Next, he designed the Pediment Sculptures for the new Harrah’s Casino in New Orleans (1999), also in the classical style, evoking the sculptural forms on the pediments of traditional Greek temples. That same year he created a popular poster depicting Professor Longhair for the 1999 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

In 1999, he was the subject of a retrospective photography exhibition (including more than 175 photographs), organized by the Contemporary Art Center. Reviewing this exhibition, critic Doug MacCash referred to the international appeal of Dureau’s photographs, seen in cities as diverse as Houston, Texas; New York City; and Paris, France. MacCash compared Dureau’s photographs to those of Robert Mapplethorpe—correctly noting that Dureau was the influence on Mapplethorpe, not the reverse, in the years from 1979 to 1981—and offered a focused comparison to the Storyville photographs of Ernest Bellocq, noting the shared human quality in both Bellocq’s and Dureau’s images. He concluded his exhibition review with the following statement: “Dureau’s theme, at its core, is flawed beauty. His photos imply the fate of homosexuals, normal human beings irreparably afflicted in society’s eyes. They bring to mind the South, a region of stunning beauty and bounty that remains tainted by the legacy of slavery. And they are glimpses of the collective soul of man, a creature created in the image of God, but scarred by vanity and avarice. Such is the importance of this work, and this once-in-a–lifetime exhibition.”

Dureau’s life and career have been the focus of a number of museum exhibitions in recent years, including Finished and Unfinished: Works by George Dureau at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in 2006, Gentlemen Callers: Paul Cadmus and George Dureau from the Collection of Kenneth Holditch at the New Orleans Museum of Art in 2008, Then & Now at the Contemporary Art Center in 2011, and Dureau, a retrospective exhibition of paintings, drawings, and photographs at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in 2011. His art is included in numerous museum collections, including the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, and the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia.