Charles Reinike

Charles Henry Reinike was one of New Orleans' most respected artists and art teachers from the late 1930s until his death in 1983.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

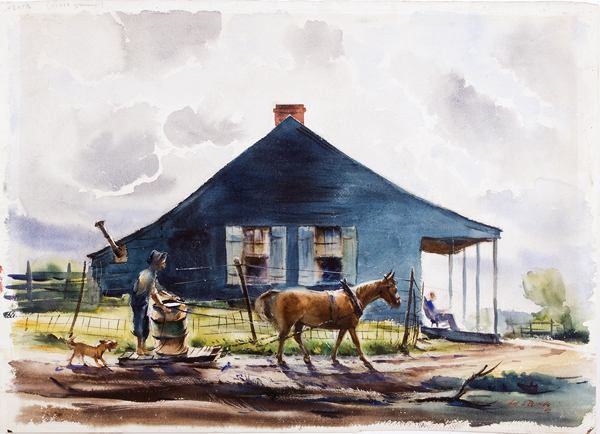

Riding the Skid. Reinike, Charles Henry (artist)

Charles Henry Reinike was one of New Orleans’ most respected artists and art teachers from the late 1930s until his death in 1983. He was born in New Orleans on July 25, 1906, to a family of German extraction; his father was a grain broker at the New Orleans Cotton Exchange. Reinike had planned to study medicine until an artist in the neighborhood saw the young Reinike’s sketches. Impressed, she gave the boy drawing lessons. He was hooked. Reinike went on to study art at the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans and the Gradham School of Art in New Orleans. He worked for a time as a commercial artist, and then in 1928 went to Chicago, Illinois, to study art at Academy of Fine Arts. It was there he met Vera Hefter, a young German art student from Hamburg, who later became Reinike’s wife and a well-known muralist in New Orleans.

In 1930, at the beginning of the Great Depression, Reinike returned to New Orleans and opened an art school in the New Orleans Art League building at 630 Toulouse Street in the French Quarter. Vera, however, remained in Chicago until 1932, when she traveled to New Orleans and the two were married.

In their French Quarter art school, the two young artists worked with many of the city’s best-known artists. In the hot summer months, the Reinikes and their students escaped on field trips to such places as St. Martinsville, Louisiana; the Jourdan River on the Mississippi Gulf Coast; and West Feliciana Parish, where they eventually bought land and operated an eight-week summer art camp at Bains, Louisiana, near St. Francisville. The Reinikes invited other established artists, such as Clarence Millet, Morris Henry Hobbs, and Louise Sarrazin, to teach at the summer camp. Reinike also taught art classes in Thibodaux and Morgan City, Louisiana.

Joining the ranks of his peers, Reinike worked for the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), an employment relief agency begun as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. During World War II, Reinike engaged in a stint with the U.S. Coast Guard and a job at Higgins Industries in New Orleans, manufacturer of the U.S. Navy’s landing craft and PT boats. Reinike’s job was to translate blueprints into three-dimensional drawings for workmen who could not read two-dimensional blueprints. A year before the war ended, the Reinikes closed the school but kept the space as a gallery.

Reinike was a noted genre and landscape painter whose work revealed a deep affection for New Orleans and the bayous and clay hills of rural South Louisiana. That passion is evident in the subjects and bold colors of his artworks. His paintings didn’t trivialize ordinary city working people, black and white sharecroppers, dirt farmers, or subsistence fishermen. Nor were they commentaries on urban and rural poverty. He respected his subjects’ dignity and, as a result, worked easily among them.

His paintings, especially those from 1935 to 1952, are visual proof of a way of life in Louisiana that no longer exists. “He liked the grittier side of things,” wrote his son Charles Reinike III, who is an artist and gallery owner in Atlanta, Georgia. “He was passionately in love with Louisiana wetlands and plantation country. He loved depicting rural Louisiana and is noted for chronicling the early African-American cabins and lifestyle for their honesty and simplicity, as well as the residential and industrial scenes of New Orleans and the Mississippi River, and the beauty of the bayou and shrimp boats.”

Like most artists, Reinike experimented with various styles during his career. Though he worked in several media, watercolors were his favorite. “Watercolor is more of a touch, almost like playing a piano,” he said. By the mid-1950s, Reinike began exploring abstract expressionism. Abstraction, he later said, gave him little satisfaction, and he gradually moved back to a style that combined abstract elements and his earlier work. “I don’t want it to be too obvious,” he said. “I want people to see what is part of themselves in that painting.” His daughter Gretchen Reinike Eppling believes her mother’s death in 1969 was the turning point at which her father returned to the more figurative work that Mrs. Reinike enjoyed. In 1975 Reinike married his second wife, Marianne Greene Cummins.

Though watercolor was his favorite medium, Reinike was as comfortable in working with oils and pastels as he was in designing monumental works in wood and metal. When he wasn’t teaching art or creating paintings for art shows, he did commissioned portraits, murals, and three-dimensional sculpted installation pieces for commercial buildings, private homes, and churches. His notable New Orleans-area murals and mosaics are at the historic Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel on North Rampart Street, Mercy Hospital Chapel on North Jefferson Davis Parkway, and a large mural he completed with son Charles at West Jefferson Hospital in suburban Marrero, Louisiana.

“He was a major contributor to the New Orleans art scene from the 1930’s to 1983,” wrote Charles Reinike III. “Not only was Reinike a painter, but he also created relief sculpture in pewter and installations throughout the city in various other materials from inlaid felt to fired enamel on copper, fired tiles. Reinike was a noted art teacher and was frequently a guest on radio and television and considered an authority on art. He had a regular nighttime radio show about art and art theory on New Orleans’ WWL radio station in the early 1950s with [local media personality] Leon Soniat (aka John Kent) who was one of his students. Reinike was very progressive in his view of art and experimental in his vision and execution, but always believed in mastering the fundamentals.”

During his long and successful career, Reinike exhibited his work throughout the South and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia; the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois; and the National Academy of Design in New York City. His work won numerous awards, and in 1976 the Louisiana State Museum in New Orleans hosted his solo show. In 1981, The Historic New Orleans Collection mounted a large retrospective of his early work. Arts patrons Mildred “Sunny” Norman and her late husband Peter Roussel Norman, a long-time Reinike friend and collector, donated a number of Reinike’s paintings and drawings to both institutions. Reinike died in New Orleans on October 27, 1983, and is buried in the city’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Reinike’s work can be found in numerous private and public collections, including the Louisiana State Museum; the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans; the Smithsonian Institution; and the Mint Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received many grants and awards for his work, including several Depression-era WPA grants; the Seven States Art League prize for watercolor 1936–37; a Best Watercolor Award from the Fine Arts Club for Comes a Storm; an award from the Mint Museum in 1940 for Corner Light; the 1940 Ellsworth Prize from the Delgado Museum of Art (today the New Orleans Museum of Art); and numerous best of show honors from the New Orleans Art Association, including in oil for 1937, 1938, and 1941, in watercolor for 1940,1941, and 1945, and in etching 1941,1945, and 1946.