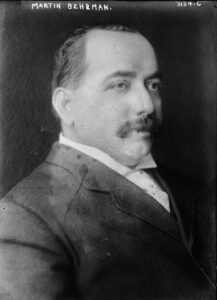

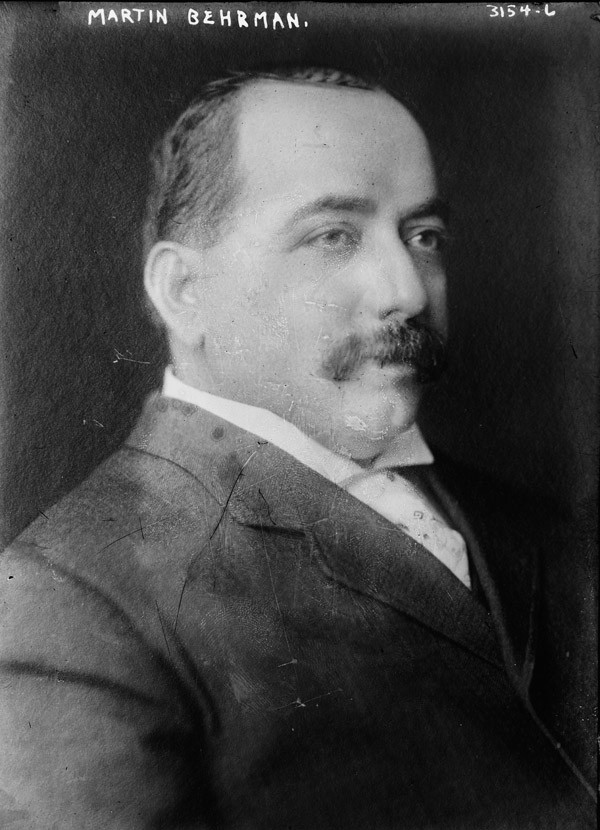

Martin Behrman

Martin Behrman was the longest serving mayor in New Orleans history.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Martin Behrman. Bain News Service (publisher)

The longest serving mayor in New Orleans history, Martin Behrman served as mayor from 1904 to 1920 (when he was defeated by reform candidate Andrew McShane) and then again from 1925 until his death nine months later in 1926. Behrman benefited from the support of a powerful political organization called the Choctaw Club, which afforded enough access to and cooperation from the local and state government to allow him to pursue several important infrastructural advancements in the city. Though some found Behrman’s political machine domineering and corrupt, his administration was responsible for crucial improvements in city services and public facilities, most notably sewage and water systems, streets, drainage, the port, and public schools. During Behrman’s tenure, the Storyville red-light district was shuttered, the Public Belt Railroad was established, and the 1912 City Charter resulted in the city council adapting a commission form.

Childhood and Family

Born to Jewish-German immigrants in New York City on October 14, 1864, Behrman moved to New Orleans with his parents when he was seven months old, just after the end of the Civil War. His father, Henry Behrman, died when he was very young and his mother, Frederica Behrman, died when Martin was twelve. Raised in his boyhood at a home at the corner of Bourbon and St. Philip streets in the French Quarter, Behrman attended the German-American School, where renowned Tulane professor J. Hanno Deiler was instructor, and later St. Philip’s Public School (now McDonough 15), while his mother worked as a vendor at a stall at the French Market. Around the age of ten, Behrman began assisting his teachers in teaching classmates whose families had immigrated from Italy, Greece, Austria, and the Slavic regions how to write in English. His mother’s death forced an orphaned Martin to find a job and, eventually, drop out of school. He worked for various groceries and food distribution companies, working his way up from cashier to salesman. During this period, he moved to the Algiers neighborhood (on the West Bank of the Mississippi River in Orleans Parish), where he would live for the rest of his life. In 1887, at age twenty-two, Behrman married Julia Collins of Cincinnati. The couple had eleven children together, although only two, Helen May Behrman and William Stanley Behrman, reached adulthood.

Political Career

Behrman served as a member of the Algiers volunteer fire brigade, a group in which he began to foster political connections. In 1888, he worked for Francis T. Nicholls’s successful campaign for governor and as patronage for his support was awarded the post of deputy assessor of the Fifth District of New Orleans. In 1892, he lost his appointment as deputy assessor when a new governor, Murphy J. Foster, Sr., took office. But in the same 1892 election, Behrman was elected a member of the Orleans Parish School Board, and he received the clerkship of several City Council committees from incoming New Orleans mayor John Fitzpatrick.

In 1896, Behrman was appointed assessor for the Fifth District of New Orleans, this time by Gov. Foster’s administration. The following year, Behrman helped organize the Choctaw Club, which soon established itself as a powerful entity in local and state politics. Behrman served as assessor until 1904, when he briefly accepted the position of state auditor before the Choctaw Club offered to support him in a campaign for mayor. Behrman amassed 13,962 votes in the 1904 mayoral election to defeat his opponent, Charles F. Buck, who garnered 10,097 votes. Buck’s camp later alleged that this election was rife with voter fraud.

Behrman took office in a New Orleans suffering from several critical shortcomings. The city needed to modernize its drainage, roadways, riverside docks, and school system. However, New Orleans’s debts, in some cases dating back to Reconstruction, stunted development. Mayor Behrman found some budgetary relief in funds generated from the sale of the Canal Street ferry franchise. In another measure to alleviate the city’s fiscal woes, Behrman worked to change the city’s policy toward accepting interest on its funds held by private banks. By 1907, the city began to receive interest on these city funds, which provided a new source of revenue.

Having diminished, though certainly not eliminated, the city’s financial problems, the Behrman administration undertook several public improvement projects. When Behrman entered office, few New Orleanians used a public water system limited by poor water pressure and capacity to reach only a small portion of the city. This acute need for modernization of the water system was underscored in 1905, when the city suffered from an outbreak of yellow fever borne by mosquitoes—which bred in the open-air cisterns that people used in lieu of a functioning public water system. The city soon began work on a new sewerage system, and by 1915 almost half of the city’s buildings were serviced by it. Behrman also looked to modernize and maintain the city’s roads by building a city-owned asphalt plant instead of paying private contractors’ high prices. Ceremoniously marking his role in establishing the Public Belt Railroad—a small freight line servicing docks along the Mississippi River that provided dependable, twenty-four hour service (as opposed to the existing, unreliable private lines), Behrman drove a golden spike into the track during the Public Belt’s construction on July 3, 1906.

In 1920, Behrman lost to Andrew McShane in his bid for a fifth consecutive term as mayor. The reform-minded McShane campaign charged that Behrman’s administration had not solved the city’s public sanitation problems. Furthermore, McShane appealed to voters who found Behrman’s lack of term limits distasteful. After his defeat, Behrman remained a political player and asserted his influence in Henry Fuqua’s successful 1924 Louisiana gubernatorial campaign. Behrman ran for mayor again in 1925 and narrowly defeated John Maloney. Behrman planned to continue working on public works improvements in his fifth term, including the construction of a municipal auditorium and the development of the southern Lake Ponchartrain shoreline, but he died nine months into this term on January 12, 1926. His body lay in state at City Hall, where thousands of mourners visited before a funeral service at St. Louis Cathedral. Behrman is buried in Metairie Cemetery.

Legacy

At the heart of the Choctaw Club political machine—which some historians have likened to New York City’s Tammany Hall, notorious for the graft and influence-peddling of its leaders such as William M. “Boss” Tweed—Behrman presided over a period of marked improvement in the city’s infrastructure. By the time of his death, he could list among his achievements the improvement and expansion of the sewerage and water system, the creation of the Public Belt Railroad, expanded public parks, and the construction of about one-third of Orleans Parish public schools. Behrman is often thought of as a pro-business mayor. But Behrman, repeatedly accused of handing out contracts to political or personal friends, is also a symbol of a system of political patronage that continues to corrupt New Orleans’s municipal functioning to this day.

The Behrman name is honored across the metro New Orleans area with several streets, a high-school football and athletic stadium, and a charter school, located in the neighborhood in which he lived.