Roosevelt Sykes

Barrelhouse pianist Roosevelt Sykes's style mixed rural and urban influences in bravura performances that some popular music historians consider the foundation for all modern blues piano.

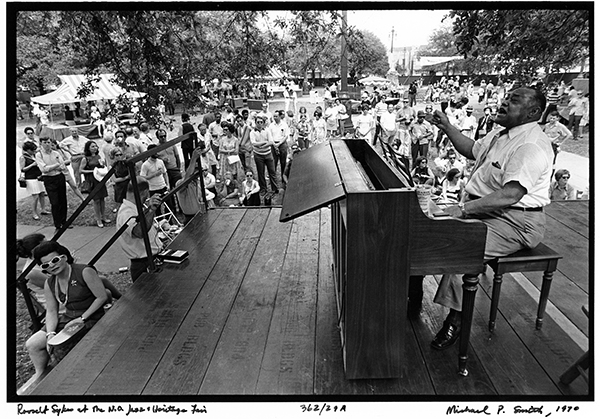

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Roosevelt Sykes at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Smith, Michael P. (Photographer)

Nicknamed “The Honeydripper” early in life for his genial personality, motivating keyboard prowess, and charming on-stage persona, Roosevelt Sykes was a happy-go-lucky, rotund, cigar-chomping barrelhouse pianist whose sixty-plus-year career spanned both the pre– and post–World War II periods. His style mixed rural and urban influences in bravura performances that shaped modern blues piano. He recorded for more than a dozen record labels, sometimes using a pseudonym to avoid contractual conflicts, and left several blues standards behind, including “The Honeydripper,” “44 Blues,” “Driving Wheel Blues,” “Night Time Is the Right Time,” and “Sweet Home Chicago.” Blues record label Blind Pig in Chicago, Illinois, has described him as a “consummate entertainer who truly enjoyed singing and playing piano for lively, appreciative audiences,” while music biographer Bill Dahl has declared that “precious few could boast [his] thundering boogie prowess.”

Born on January 31, 1906, in the small sawmille town of Elmar, Arkansas, Sykes spent significant time in nearby Helena and the larger cities of St. Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois, toward the end of his career before retiring to New Orleans, where his influence was felt especially among musical luminaries of the city, including Fats Domino, Champion Jack Dupree, Professor Longhair, and even Ray Charles. Posthumously inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1991, the Blues Foundation lauded Sykes’s ability to weave “his rural and urban blues sensibilities with intricate chord patterns and bass figures.” He not only shined as a solo performer and recording artist, but was equally adept when providing accompaniment for more than thirty singers during his long career.

From Work Camps and Urban Nightclubs to Major Recording Labels

Although Sykes’s family moved to St. Louis when he was three years old, the would-be pianist continued to spend significant time in rural Arkansas. “Every summer I would go down to Helena to visit my grandfather on his farm,” he told biographer Valerie Wilmer. “He was a preacher and he had an organ I used to practice on, trying to learn how to play. I always liked the sound of the blues, liked to hear people singing, and since I was singing first, I was trying to play like I sang.” Having mastered the keyboard by the age of ten, he soon began traveling the well-worn routes of rural blues musicians in the upper South and lower Midwest, playing all-male work camps created for manufacturing turpentine, producing lumber, and building levees. These were the same sites and rowdy audiences that had once provided an incubator for ragtime.

During the 1920s Sykes also spent time in the more urban surroundings of Helena and St. Louis, studying the styles of blues pianists he encountered there. One of his most prominent mentors, Leothus Lee “Pork Chop” Green, likely schooled Sykes in mastering separate but complementary bass and treble rhythms. In St. Louis, Sykes met and eventually partnered with singer-guitarist “St. Louis” Jimmy Oden, best known for his enduring blues classic, “Going Down Slow.” In 1929, during an era of consolidation within the blues recording industry, Sykes made his first recording at age twenty-three. He eventually recorded for major labels Okeh, Decca, Bluebird, and RCA Victor, along with a host of independent labels.

Following the Blues Revival to European Festivals and New Orleans

Around the mid-1950s, as electric blues bands began to dominate the Chicago blues scene, Sykes established a base of operations in New Orleans but often traveled to Chicago and Europe to participate in the blues revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s. By the time he settled more permanently in New Orleans during the late 1960s, Sykes was welcomed with open arms into the city’s own popular-music revival, presaged and driven to some extent by the nascent New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, established in 1969. Having logged successful career segments in cultural environments that ranged from rural turpentine camps to inner-city nightclubs, international music festivals, and even New Orleans’s uniquely cosmopolitan music scene, Sykes’s long career was marked by the personal belief, as he confided to his biographer, that “blues is a confessional thing, and people always did like the truth.”