Lagniappe

"Lagniappe" is a vernacular word used in New Orleans to refer to a complimentary giveaway in a retail environment.

Project Gutenberg

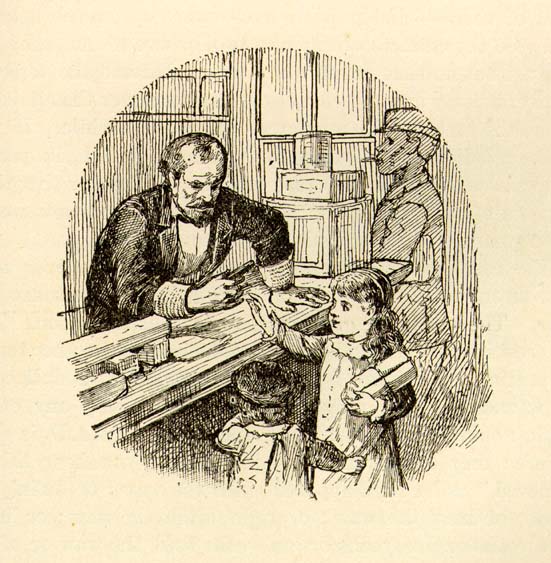

Lagniappe as depicted in Mark Twain's "Life on the Mississippi," 1883.

Lagniappe is a vernacular word (pronounced LAN-yap) used in New Orleans to refer to a complimentary giveaway in a retail environment. For example, when New Orleans grocers or bakers present candy or an extra cookie to customers’ children, they call the custom “lagniappe.” Defined as “something given over and above what is purchased, earned, etc., to make good measure or by way of gratuity” by the Oxford English Dictionary, the term appeared in Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi early in its journey beyond New Orleans and into the English language. The word is reportedly derived from the Quechuan yapay, meaning “that which is added to the principal thing.” Linguists believe that Spanish colonists of the former Inca Empire in Peru borrowed yapa as la ñapa. They brought the word to Louisiana, where French-speaking residents combined the article and noun to form lagniappe. The term is still used to refer to small gifts that merchants offer to customers and is sometimes extended to apply to any unexpected benefit encountered in daily life.

The “Curse” of Lagniappe

Current exchanges represent a tamed variation of the lagniappe that flourished in the late 1800s. Grocers who gave shoppers’ children small treats eventually found that the parents then expected them to provide lagniappe portions of meat, sugar, butter—any food item that would complement their meager purchases. The practice was reportedly most prevalent in the French Market and other less affluent downtown neighborhoods: older women would shop late in the morning, when perishables were marked down, trying to spend as little as possible while still qualifying for “something extra.” A Daily Picayune report from 1885 describes one shopper’s penny-pinching strategy: “From each seller she gets her lagniappe: from the butcher it is a couple of cracked bones to make a good sauce-pan full of soup; from the grocer it is a pinch of kraut or a few shreds of noodles; from [another] grocer it is a young onion, a sprig of parsley, and a half of turnip; from the breadwoman it is two little tasteless rolls made expressly for lagniappe.”

The large numbers of impoverished immigrants and other poor people in New Orleans during the late 1800s caused bakers, grocers, butchers, vegetable peddlers, and others to be “afflicted with the twin evils of ‘quarti’ and ‘lagniappe,’” as a 1907 report in the Duluth News-Tribune (Minnesota) asserted. A quartee (the more common spelling) portion was equal to one half of a nickel’s worth of an item. Once customers had spent five cents in most shops, they believed they were entitled to lagniappe. One might purchase a quartee portion of red beans and a quartee of rice with the expectation that the grocer would include a small piece of ham as lagniappe. A purchase of a quartee of bread and a quartee of coffee would qualify the customer for a lagniappe portion of sweetened condensed milk, thus forming a whole breakfast. Since bread loaves sold for five cents, though, most bakers were required to carve a loaf in half.

Every small business had to be prepared to appease their adult customers with extras: “There are groceries in the French Quarter where the chief business of the supplemental small boy is the rolling of brown paper sheets into cornucopias and the filling of these horns of plenty with Lagniappe,” the Chicago Times reported in 1886. Sugar, spice, and candy were the most typical offerings; however, many customers directly announced what sort of lagniappe they had in mind. Customers often stated their preferred item by inserting it into a well-known rhyme: “Quartee red beans, quartee rice, lagniappe salt meat to make it taste nice.” While grocers handed out lagniappe for every five-cent purchase, some customers would even demand “two lagniappe” when purchasing a quartee portion of beans and the same portion of rice.

Such obligations placed upon small-business owners suggest how influential the poor and working class were to the culture of the city. A Minneapolis journalist visiting in 1899 marveled over the amount of food that could be eked out of a few cents here: “The French merchant will tell you that you can purchase more with a nickel in New Orleans than in any city in the United States. Where else can you buy a hot lunch of sausage, potatoes, and cabbage, or stewed meat and potatoes, etc., with a hunk of bread thrown in, for 5 cents; or a whole dinner for ten cents?…Yet notwithstanding the cheapness with which everything can be bought, these Creole women have, so to speak, chopped the nickel into two parts.”

In fact, brass or tin quartee chits worth two-and-a-half cents circulated in New Orleans to accommodate the penny-pinching shoppers. Providing a piece of candy for customers’ children was widely accepted and far less controversial for the shopkeepers. Wholesalers sometimes offered discounted prices for broken stick candy specifically for use as children’s lagniappe. Token candies or cookies for children presented little hardship for the small businesses.

The Anti-Lagniappe Campaign

Although retail shop owners resented their customers’ demands, grocers did not dare refuse lagniappe and risk losing business to neighboring stores. Late in 1906, however, approximately 1,500 retail grocers in New Orleans collaborated to declare an end to the practice at the start of the next year. Representatives visited the poorest downtown areas, the French Market, and neighboring shops to distribute “Anti-Lagniappe” signs, and the New Orleans Retail Grocers Association created a committee intent on stamping out the practice by the start of 1907. The committee head swore he would never revert to providing lagniappe, claiming that he could have purchased a “square of ground” with his cumulative losses.

The Grocers Association had the support of the Board of Health, which claimed that the obligatory ritual had led to children ingesting rotten candy: shopkeepers seeking to lower the cost of lagniappe often opted to dispense old, even spoiled items. Despite such negative effects, many parents regretted the loss of lagniappe because the expected treat had served as an incentive for children to run errands.

The city’s bakers immediately followed suit, but lagniappe in its other forms could not be immediately ended. Almost three years later, the Orleans Pharmaceutical Society established a committee to help suppress lagniappe. Just how extensive the practice must have been is evident in the “No Lagniappe” sign posted in a Chinese laundry in 1913. This message and similar “Anti-Lagniappe” signs distributed to groceries gradually prevented shoppers from requesting their customary reward. Extra effort made by trade organizations and special committees responsible for enforcement of the policy were required to tame the local practice. Eventually, a permanent truce in the lagniappe war was struck: it allowed the tradition to survive in less expensive forms, such as the presentation of candy for children.

Lagniappe continues to be a popular term in the highly localized jargon of Louisiana. The weekend entertainment section of the Times-Picayune newspaper is titled Lagniappe, as is the yearbook for Louisiana Tech University in Ruston. Jazz musician Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews titled an original composition “Lagniappe, Part 1 and Part 2” on his 2011 album For True, and the word has been applied to numerous cookbooks.