William S. Burroughs

William S. Burroughs called New Orleans home for a brief but dramatic period from 1948 to 1949.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

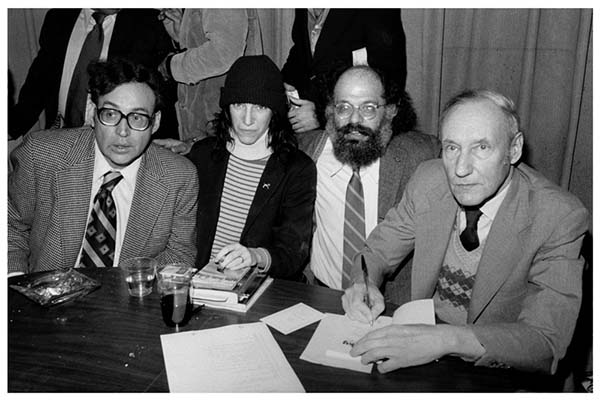

William S. Burroughs and Friends. Noah, Marcelo

William S. Burroughs was an American writer known for his daring, experimental novels that shook conservative conventions in the 1950s and 1960s. His books were controversial—and even illegal—due to their sexual explicitness, profanity, and raunchy humor. Though Burroughs lived on four continents throughout his lifetime—often skipping from country to country to evade the law—he called New Orleans home for a brief but dramatic period from 1948 to 1949, making his residence in the Algiers section of the West Bank.

Burroughs is closely affiliated with such Beat Generation writers as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, but he never fully identified with that movement. Rather, as an openly bisexual man (which was punishable by law for much of his lifetime), Burroughs explored the shunned and persecuted fringes of society and embraced a lifestyle that even by today’s standards would be considered radical. He blazed a remarkable cultural and literary trail through most of the twentieth century, often while on the lam to avoid imprisonment for multiple offenses. He was also in and out of rehabilitation clinics for his epic, well-documented battle with opiate addiction. Throughout these ordeals, he managed to write eighteen novels and novellas, six collections of short stories, and four volumes of essays. He produced several spoken-word albums and five books comprised of interviews and correspondence. In his later years, Burroughs became such a living legend that he was a sought-after collaborator on music and film projects, working with such artists as The Beatles, Tom Waits, Frank Zappa, Gus Van Sant, Nick Cave, Sonic Youth, R.E.M, and Kurt Cobain. He is credited with coining the phrase “heavy metal,” which became its own musical genre; even the band Steely Dan took its name from a sex toy Burroughs described in his breakout 1959 novel, Naked Lunch. He died in 1997 at eighty-three years old.

Early Rumblings

Burroughs was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1914. His father, Mortimer, was a successful business owner. His grandfather, William S. Burroughs I, was founder of the Burroughs Adding Machine Company, which later became the Burroughs Corporation.

Burroughs attended the prestigious Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico, where he developed several of the passions that would define him throughout his later life: his affection for guns, his homosexual eroticism, and his penchant for illegal drugs. Publicly, he proved himself to be an accomplished marksman; privately, his journals would reveal an erotic attachment to another young man. His time at the school was cut short, however, when he was expelled for taking the sedative chloral hydrate.

After graduating from Harvard University with an English degree in 1936, Burroughs traveled to Europe and enrolled briefly in medical school. In Vienna, he was able to explore his gay sexuality outside of the prudish American cultural and political landscape, which looked on homosexuality as either a mental illness or a crime, both punishable by institutionalization. He also met Ilse Klapper, a Jewish woman fleeing the country’s Nazi movement. Burroughs married her in order to gain her access to a US visa. They were never romantically involved and eventually divorced, but the couple remained friends for many years after she was safely settled in New York.

Burroughs himself returned to New York in the early 1940s and fell in love with a man named Jack Anderson. When Anderson broke off their relationship, a distraught Burroughs chopped off the end of his own left pinky finger with poultry shears. He was committed to a mental institution for several months. Two years later, when Burroughs was drafted into World War II, his father would produce documentation of Burroughs’s self-mutilation and psychiatric condition, and the military agreed that Burroughs was not the man for them. Freed from conscription, he moved to Chicago, where the Harvard graduate became perhaps the most over-educated exterminator in the city—an experience that would play a key role in some of his later work.

Eventually, Burroughs tired of odd jobs and moved back to New York City. This relocation was a turning point, as the city introduced him to three things that forever changed his life: writer Jack Kerouac, morphine, and future wife Joan Vollmer. With Kerouac, Burroughs made his first serious attempt at literature, coauthoring a novel called And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks (1945). Meanwhile, a hustler named Hunke was trying to unload a case of stolen morphine syringes, and thus Burroughs was introduced to the use of opiates, to which he subsequently became addicted. Finally, Vollmer, whom he had met in Kerouac’s apartment, would become Burroughs’s common-law wife, partner in crime, mother of his child, and, finally, victim of his accidental manslaughter, an act that would haunt him for years.

The New Orleans Years

After an early stint in a rehabilitation clinic for heroin addiction, Burroughs moved west with Vollmer to try his hand at agriculture and marijuana farming in Texas. When that failed—his legitimate crops were subject to myriad natural and bureaucratic setbacks, and he didn’t know how to cure his own marijuana plants—he moved to New Orleans, where he lived from 1948 to 1949. Offering easy access to cheap drugs and a thriving gay subculture, the port town had an unmistakable allure, especially after Burroughs’s challenging seasons in rural Texas. He bought a house at 509 Wagner Street in the Algiers neighborhood and the family settled in. Jack Kerouac famously describes the scene in his autobiographical novel On the Road: “It was on a road that ran across a swampy field. The house was a dilapidated old heap with sagging porches running around and weeping willows in the yard; the grass was a yard high, old fences leaned, old barns collapsed.”

Other people found the state of affairs in New Orleans to be more alarming. Helen Hinkle, who was a houseguest with Burroughs for several weeks, claimed, “The household seemed to operate on the principle of total permissiveness. The children were allowed to potty wherever they liked, whether it was on the dining room floor or in the Revere Ware in the kitchen … the six-year-old girl was thin, with filthy, matted hair—apparently they washed whenever they felt like it. She had nightmares and had formed the habit of chewing her left arm, in the crook of which there was a large scar.”

If things sounded uncouth, at least they were relatively stable, but even that constancy couldn’t last. Burroughs’s time in New Orleans was about to come to an end in much the same way his time in New York and Texas had: as a failed experiment and in trouble with the law. Burroughs’s real estate investments were already beset by lawsuits and setbacks when he was pulled over by police near Lee Circle in New Orleans. In the car, the police found an unregistered handgun belonging to Burroughs as well as a letter from fellow writer Allen Ginsberg that contained details about the sale of some marijuana. The police searched Burroughs’s home, where they discovered his personal stash of drugs and half a dozen or more firearms. Burroughs was hauled off to jail, and all indications were that he was going to be convicted and sentenced to the infamous Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. His defense attorney managed to get him released on bond; while Burroughs was free to move, he took the opportunity to slide out of town and across the border to Mexico, where he could wait out the statute of limitations on his case. As they had many times before, the family packed up the home in Algiers and quickly moved on.

Career and Legacy

Aside from scattered trips home, Burroughs would spend the next twenty-four years in exile from the United States. From foreign shores, he would produce most of his literary works. He fled Mexico after accidentally killing his wife by attempting to shoot a glass off her head and spent time wandering South America. While south of the US border, he produced Junky (1953), Queer (written between 1951 and 1953 and published in 1986), and The Yage Letters (written in the early 1950s and published in 1963), the latter of which were fairly straightforward narratives. Then he moved to Paris, London, and Tangier, Morocco, where he produced the highly experimental work that would become Naked Lunch (1959), Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and Nova Express (1964), all known for their “cut-up” and “fold-in” techniques of nonlinear narrative, bizarre imagery, and fragmentary storytelling. Through the 1960s and early 1970s, Burroughs continued to experiment and branch into film and musical recording. Finally, in 1974, Burroughs returned to the United States and found his way onto the speaking circuit; for two decades, he made his living by doing public events. He wrote Wild Boys (1971) and several anthologies of articles, short stories, and other works, including Exterminator! (1973), The Burroughs File (1984), and The Adding Machine: Selected Essays (1985). In 1981 he settled in the college town of Lawrence, Kansas, and he would spend the rest of his days there. During this mature stage of his career, he produced the books Cities of the Red Night (1981),The Place of Dead Roads (1983), and The Western Lands (1987). It was also in 1981 that he was inducted into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters: the once-shunned outsider had been embraced by the literary establishment.