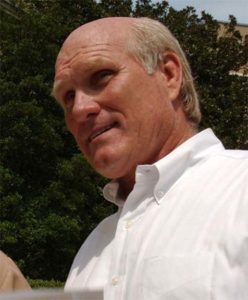

Terry Bradshaw

Louisiana's Terry Bradshaw won four Super Bowls as quarterback for the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 1970s.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

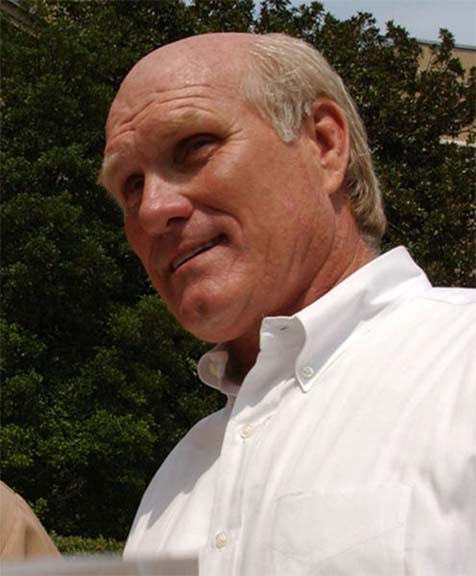

Terry Bradshaw. United States Navy

For younger generations of football fans, Shreveport native Terry Paxton Bradshaw is a goofily enthusiastic television commentator for National Football League (NFL) games on Sundays, a bald, wide-smiled verbal dervish whose personality always seems to be in overdrive in front of the camera. To football history, though, Bradshaw was the quarterback and field general for one of the NFL’s greatest dynasties, the unflappable gunslinger who handed off to fellow Pro Football Hall of Famer Franco Harris and whipped the ball to Hall of Fame receivers Lynn Swann and John Stallworth to devastating effect as their Pittsburgh Steelers won four Super Bowl titles in six years during the 1970s.

The offense Bradshaw himself marshaled—he called his own plays for the majority of his career—complemented Pittsburgh’s dominating “Steel Curtain” defense to create a team that was decidedly working-class in nature but chocked full of finely skilled football craftsmen who could slice opponents with surgical strikes just as well as bludgeon foes with a sledgehammer.

Early Life

Bradshaw’s journey to the Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio—and to the television studio and even movie set—began with his birth in Shreveport in 1948 to William “Bill” Bradshaw, a farmer and welder, and Novis Gay. Although the Bradshaws spent much of Terry’s childhood in Camanche, Iowa, the family returned to Shreveport in time for him to emerge as a football star at that city’s Woodlawn High School, which he guided to the 1965 state AAA title game. He also set a national record in the javelin for the track team.

Bradshaw then attended Louisiana Tech University in Ruston and immediately developed an attachment to the Bulldog program that has lasted his entire life. With Bradshaw at quarterback, the Bulldogs had great success, including a 9-2 record his junior year that culminated with a victory over Akron in the 1968 Rice Bowl. Bradshaw became, according to many pundits, the premier college quarterback in the country. His lifelong affinity for his alma mater reflected his commitment to his rural roots. His unabashed “country” personality often drew ridicule from the media and opponents, who mistook Bradshaw’s rustic nature for a lack of intelligence, which the quarterback disproved with crafty play-calling and a wily instinct for winning games.

Football Career

The Steelers took Bradshaw with the first overall pick in the 1970 NFL draft. While he struggled early in his career, the Steelers gradually built a winning team around him, claiming their first Super Bowl victory in 1975, with three more NFL titles to follow in 1976, 1979, and 1980. His performances, while erratic at times—during his injury-riddled career, Bradshaw threw for 210 interceptions compared to just 212 touchdowns—nonetheless earned him the 1978 NFL Most Valuable Player award, two Super Bowl MVP accolades, three trips to the Pro Bowl and ultimately, in 1989, election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was then enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1996.

After his playing career, Bradshaw branched out into other fields, running businesses and, more popularly, becoming something of a celebrity, starring in movies (including a notorious nude scene in the 2006 comedy Failure to Launch) and TV shows—he has been a guest on The Tonight Show more than 50 times—and earning a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 2013 he debuted a one-man singing and storytelling show about his life, America’s Favorite Dumb Blonde—A Life in Four Quarters, in Las Vegas. He also began medical treatment for physical and neurological problems he attributed to the trauma his body endured from thirty years of playing football. Bradshaw said he suffers from memory loss and bouts of depression; however, he opted out of a class-action lawsuit filed by former NFL players against the league for concussion-related complications, saying he preferred not to take a share of the $765 million settlement when many other former players needed the money more than he did.