Magazine

Loaded Down with Iniquity

In 1866, six madams brought a crop of new talent back to New Orleans aboard the Evening Star, but the steamer never made it to its destination

Published: October 21, 2015

Last Updated: May 15, 2021

Illustration by Toan Nguyen.

The Evening Star sank off the shores of South Carolina when it encountered a hurricane in October 1866.

Robbins, who was known for being “friendly” with Union soldiers, and King, who owned a 35-room home on Basin Street, each chose 20 girls. Burdell, who owned houses on modern-day Iberville Street, acquired 15. Kingsley brought 10 women and the others brought three to five each. The New York Daily News wrote that the madams handpicked some of the “most accomplished, handsomest and unscrupulous lorettes to be found in the gilded brothels of this city.” Various accounts set the number of prostitutes from 45 to 98.

Hours before the Evening Star’s departure, large trunks bearing such charming (and likely false) names as Rose Standish, Pauline Sinclair and Georgiana De Vere were piled near the gangway. A throng of spectators gathered to watch the departure of this large group of “frail women,” many of whom wiped away tears with their embroidered handkerchiefs, anxious, and perhaps excited, about the upcoming journey to their new homes — and places of employment. Wealthy businessmen puffed on cigars, amused as the ship’s crew appeared to be visibly excited by the cohort that would soon be under their care. The scene took on an even more curious dimension when civil marshals arrived armed with warrants sought by the women’s former landladies, seamstresses and shoemakers. Protests, tears and threats were useless as the marshals rifled through the luggage, searching for any articles with a balance. Eventually, the madams paid any debts, further obligating some of their new employees.

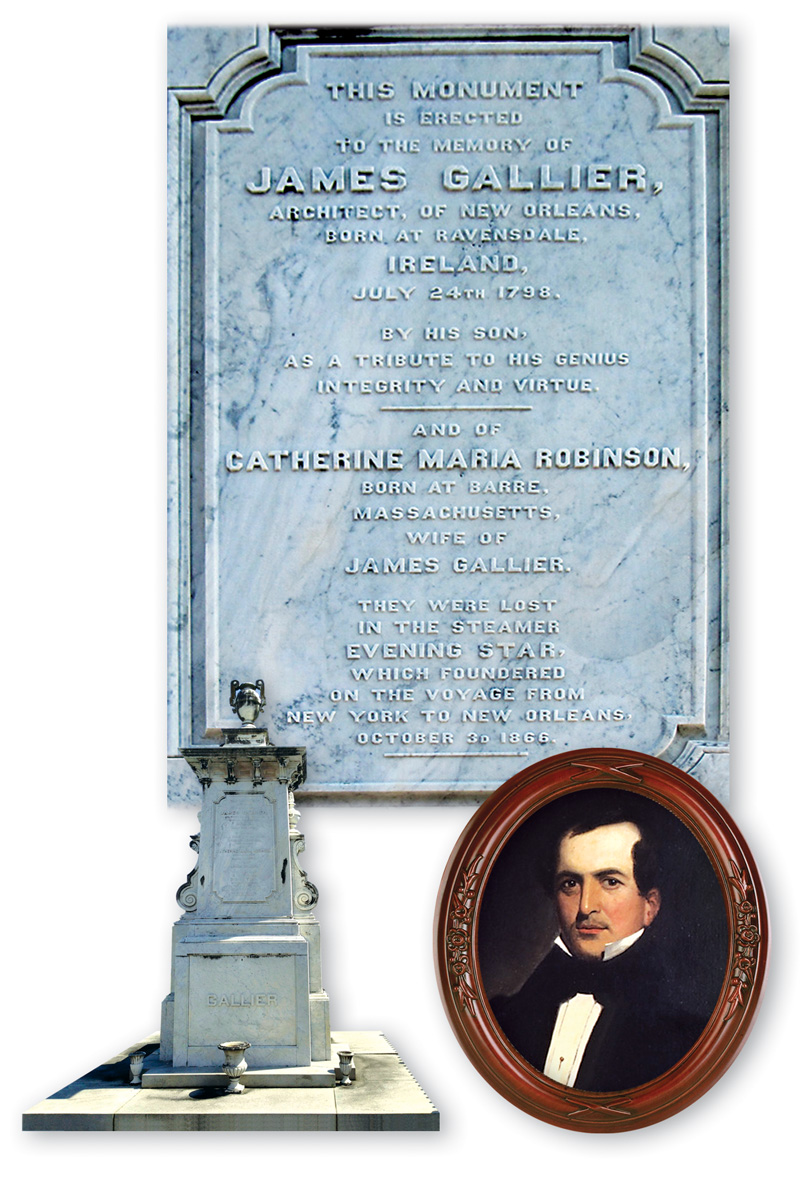

The unusual dockside scene was heightened by two other peculiar groups waiting to board the Evening Star: about 20 members of Gilbert Spalding and David Bidwell’s Circus Company (who owned and managed the New Orleans Academy of Music), and approximately 60 members of Paul Alhaiza’s Opera Troupe, made up primarily of French musicians, singers and actors. Concerned that a trip by rail would be too exhausting for the female performers, Alhaiza booked their passage on the Evening Star. He instead opted for a rail journey, possibly for a chance at quiet introspection following the recent deaths of his father and brother. Another brother, Charles, stayed with the troupe on the Evening Star. Also aboard were various members of New Orleans’ society, including James Gallier, New Orleans’ most celebrated architect; Samual Hardringe, the Yankee husband of Confederate spy Belle Boyd’s who himself had become a rebel soldier; and General Henry William Palfrey, who served as the commissioner representing Louisiana in the Exposition Universelle in Paris. The Evening Star carried a half-million dollars of merchandise, diverse passengers from nearly every class of society, as well as nearly every form of amusement — be it legal or illegal. Its journey to New Orleans would ultimately turn into a tragedy that exposed issues of class, gender, labor, and corporate greed, and the true nature and mettle of individuals in the face of peril.

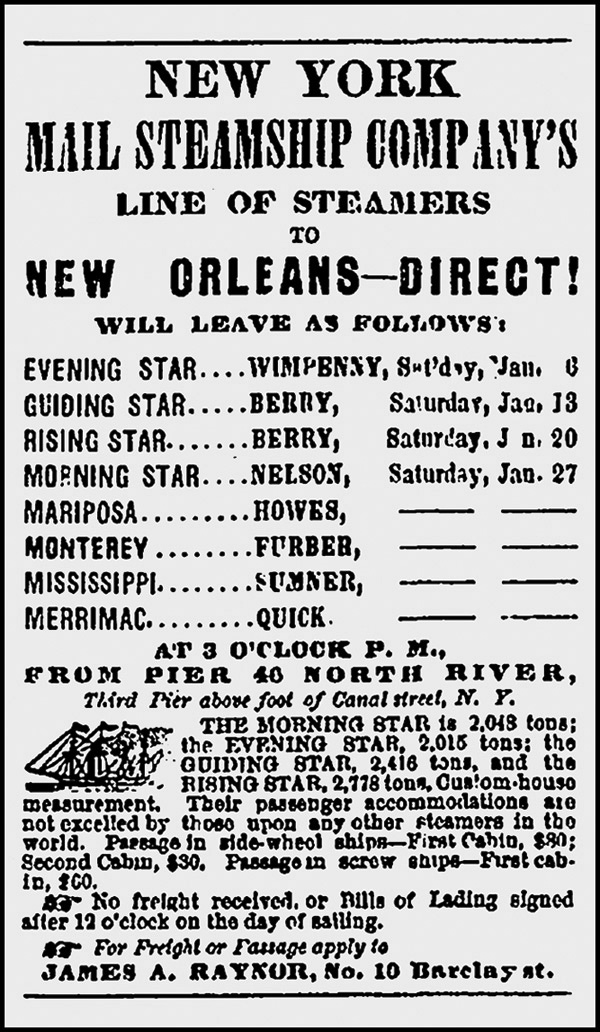

A newspaper advertisement from New York’s Commercial Advertiser lists the Evening Star as one of many ships plying the steamer route between New York and New Orleans in 1866. Courtesy of Tulane University Library

The Birth of the Evening Star

The Evening Star was launched in 1863 from New York’s East River. Isaac L. Waterbury built her for the New York Mail Steamship Company (NYMSC), which operated the luxury “Star Line of Steamships” — the Morning Star, Guiding Star and Rising Star. One of the largest and most lavish ocean steamers, the Evening Star’s primary purpose was to run a weekly line between New York, Havana and New Orleans. She weighed 2,015 tons and measured 275 feet long at the keel and over 288 feet in length, with a beam of 39 feet 4 inches and a draft of 23 feet 3 inches. Powering her side paddlewheels were two beam engines built in 1854 by Cunningham & Belknap for the railroad and intended for lake navigation, but sufficient for ocean voyages.

Almost immediately, the Evening Star was heralded as grandeur on the sea. By the end of 1863, she was the sole choice for many frequent travelers since she advertised “luxury on all sides” and allowed customers to “carry their hotel with them.” First-class tickets were $80 and second-class passage ranged from $30 to $40. The steamship also transported mail, newspapers and merchandise, and during the Civil War, officers, soldiers and prisoners. After the war, with the reopening of the Mississippi River, commercial shipping interests and travel rapidly expanded in New Orleans. Among all the steamships voyaging to and from the Crescent City, the Evening Star was prized not only for her courteous and able crew but her efficiency and speed. The average trip from New York to New Orleans took approximately a week, but in November 1864, the Evening Star made the quickest voyage on record: six days and 11 hours.

Though the Evening Star was one of the most famous and highly regarded steamships, her career was not without incident. In January 1866 she battled a severe storm for several days under the command of Captain L. C. Wimpenny, who was knocked down by a large wave and broke his right leg. He died a few days later while still at sea. The ship arrived safely in New Orleans with its passengers and crew but a “card” was published in the New Orleans Times signed by almost 40 passengers, including military officials, stating the ship was overloaded; there was no surgeon aboard; it had an inadequate amount of fresh water; some of the lifeboats were useless; the crew was insufficient; and were it not for eight accidental stowaways who performed valiant “if compulsory service,” the outcome might have been different. The disgruntled passengers added that Wimpenny was a “martyr to the inhuman policy and contemptible penuriousness of a Company whose charges are one-half more than those of other respectable lines, and one-third more than those of any other Company.” They did, however, single out purser Ellery Allen for his “indefatigable efforts to remedy and alleviate their discomforts.” Despite the passengers’ complaints, the card did not engender much concern.

Captain William Knapp took over shortly after Wimpenny’s death. After decades of service, Knapp retired from the sea almost three years earlier when his wife had premonitions of disaster, but money problems eventually forced his return. In May 1866, the Evening Star was caught for just over two days on Pickle Reef off Florida, but she eventually sailed safely to New Orleans. A bit later, the steamship encountered a heavy gale and was overhauled in July to check for damages. A garboard was scratched and the keel was split in places, extending from the middle of the ship to about 30 feet aft. Repairs were made and the NYMSC declared her seaworthy. The steamship’s difficulties did not diminish her luster as passages were often booked a month in advance. Nevertheless, on the Evening Star’s final voyage, Knapp’s one request was to telegraph his wife in Connecticut to let her know the minute the ship arrived safely in New Orleans.

Like A “Bubble on the Breeze”

On September 29, 1866, The Evening Star set sail from New York without incident at 3:30 p.m. with approximately 219 passengers and 59 crewmen. On October 1 she passed Cape Hatteras, off the North Carolina coast, enjoying calm weather. The following morning, a cold breeze from the east created a heavy swell, increasing to a gale by evening. It was soon evident that the steamship was in the middle of a hurricane 180 miles east of Georgia’s Tybee Island. Near midnight waves swamped the ship; crew and passengers frantically bailed the water that swept over her deck and rushed into the engine room and cabins. The crew built a large bulkhead in a vain attempt to hold back the rushing water — four times they erected the bulkhead and four times it was quickly broken. At 3 a.m., the main steampipe broke due to the strain and the starboard rudder chain was thrown out of its sheave from the ship’s violent rocking. The crew cut a hatch in the lower cabin deck to get to the water, which had completely breached the ship. To power the steam pump and remove water from the engine room, the crew lit the auxiliary boiler, but it soon broke and the ship was engulfed more quickly than before. Female passengers assisted in bailing using various appliances, even stripping off clothing and accessories so as to not impede their movements. Watches, lockets, rings and precious stones of immense value littered the deck, awash in frothy seawater. Members of the French opera troupe had difficulty understanding instructions, made worse by the deafening wind, but assisted as best as they could. Men and women shouted encouragements and kept a steady pace, but it quickly became apparent that their efforts were futile. The steamship was in the trough, with her side to the weather and “mountainous” waves breaking over the main deck. With the engine hatch broken, the waves extinguished the boiler fires, leaving the Evening Star dead in the water. Passenger W. H. Harris, a merchant from Williamsburg who frequently traveled by ship, described the steamship as being tossed around like a “bubble on the breeze.”

Just before daybreak on October 3, with the tempest at full strength and the ship powerless and broken, Captain Knapp announced that all hope was lost; it was up to the passengers to save themselves as best as they could. The Evening Star would go down.

Drawing by Toan Nguyen

“Self-Preservation is the First Law of Nature”

The Evening Star had six lifeboats and one other small boat — enough, the company claimed, to hold everyone on board. Each lifeboat came equipped with oars, bread and water but not enough life preservers. At first, passengers piled into the lifeboats, but they were torn from their davits and proved impossible to launch in the rough winds and with water sweeping over the deck from stem to stern. Each launch attempt was thwarted. Some accounts claim that one lifeboat was launched and upon touching the water, it immediately capsized. The occupants were washed away, and no more attempts were made. Other accounts claim that all of the lifeboats were launched and subsequently capsized, that a few were cut free while some remained attached to the ship, or that none were able to launch. Regardless of which story is true, what is evident is that boarding a lifeboat to escape was not an option.

Unable to abandon the sinking ship, some passengers clung to the rigging, while others, mute with fear and immobilized, held hands. Some, consumed by hysteria, hurled themselves into the sea, while others tore off their clothes and ran wildly around the ship. Some returned to their cabins, while others crouched in the corners of the saloon, not seeking their deaths like those who threw themselves overboard, but waiting for it nevertheless. Some knelt to pray, hoping to find peace in the chaos and that God could hear their prayers over the screeching wind.

W.H. Harris described how one passenger (believed to be General Palfrey) clasped his wife and two small children tightly, remaining in that position until a surge rushed through the saloon and death washed over them. A crew member stated that James Gallier and his wife tried to support themselves in their stateroom when the ship broke apart and “yielded to the raging fury of the storm.” Frank Girard, a popular Ethiopian comic with the circus, stated that the “lewd women” prayed, cried and took turns berating the crew while the respectable women quietly resigned themselves to their fate. Harris noted that from the passengers of “low in moral feelings,” one distinguished herself — Flora Burdell. Despite shipping young women for her “odious traffic,” Burdell took the lead at the first signs of danger. “When bailing she acted like a man, and a good man at that,” Harris maintained. “When the boats were lowering she handled them well, and appeared to know as much about them as men whose lives had been passed on the ocean.” Burdell went down with the ship.

The Evening Star was pulled under around 6 a.m. Girard wrote, “the force of the vortex whirl[ed] me about as if I had been a chip.” Girard reached the surface before his lungs gave out and held on with 16 others to a broken piece of deck. Wave after wave struck until only Girard was left. After hours in the water, Girard saw a lifeboat nearby, but discovered its occupants unwelcoming. A crewman tried to block him with an oar but Girard managed to toss the man aside and climb inside, only to have a wave capsize it moments later. The historical code of conduct dictating “women and children first” (known as the Birkenhead Drill for the 1852 evacuation of the Royal Navy Troopship HMS Birkenhead) was not only completely abandoned but brutally reversed. In a letter to his friend, and later in an interview with the Prairie Farmer, Girard depicted the crew as “fiends” who robbed passengers of their money and jewels. Harris also stated that many crew members were drunk and claimed lifeboats for themselves. Girard described horrific scenes of seamen threatening to kill lifeboat passengers by smashing in their heads with driftwood if they attempted to take in any additional survivors. He described how one sailor sliced a young French boy’s fingers with a knife who clung to the side of his boat: “As the lad dropped into the sea, he turned his beautiful blue eyes upon the brute that cut him, with such a look as I would have not cast upon me for all the world.”

Each time Girard’s lifeboat capsized, it lost some survivors and occasionally gained others. On a large piece of debris, a raven-haired girl knelt in prayer. Her clothes torn from her body, she had a large bleeding gash on her left side. Her father, clutching a rope attached to the debris, swam to Girard’s lifeboat, but as he reached out to give Girard the rope, he sank beneath the water, never to resurface. Girard slowly pulled the girl toward him but when she was just a few feet away, a wave washed over her and she joined her father below. Another woman clinging to a piece of debris nearby cried “Gentlemen, for God’s sake take me into the boat.” As Girard reached for her, one of the crewmen raised a board and growled, “Take that woman into this boat and I’ll brain you.” Another gentleman restrained the “brutal sailor,” but as Girard reached for her, she too was swept away.

There was an equal chance of being killed by something floating in the water as there was of being lost under it. Scattered fragments of timber and decking became life-saving devices for some, while others met their deaths by the very same objects. People were helpless to dodge the crashing debris hurled in all directions, lacerating, crushing, even decapitating. The sea was a washing machine of flotsam with pieces of the ship, luggage, bodies and severed heads being tossed about, as people clung to anything to stay afloat. But worse than the waves’ wallops, the salty sting spray, and the wind’s howls were the shrieks and pleas from those struggling to stay alive. The few crew members and passengers who survived the shipwreck soon learned that the open ocean, under the unforgiving sun and without supplies, could be just as deadly as the fiercest hurricane.

Death in Lifeboats

Chief engineer Robert Finger and purser Ellery S. Allen had been with the Evening Star since her inaugural launch and were on deck when the ship went down. Allen struggled in the water and wind for three hours, dodging flying debris, ultimately suffering a sliced cheek and a nearly severed upper lip before joining 19 others, including Finger and passenger W. H. Harris, in a lifeboat that capsized six times. Harris was standing by the hatches when a wave swept him off the deck. He managed to grab a piece of the saloon but was continuously thrown into the roiling ocean. He lacerated his hands, arms and legs on nails and splinters before he made it to the lifeboat. After one capsizing, Finger drifted for almost seven hours until he was able to get back to the lifeboat. Harris noted that a young girl (believed to be Mademoiselle Du Mery of the French opera troupe) held on to the boat for hours. The boat capsized many times but she managed to hold on until the fourth time, when she was lost.

Finger and Allen’s lifeboat drifted at the mercy of the sea, passing and re-passing the wreckage until the next evening when they lost sight of it. Without food or water, some drank seawater, which Harris said “made them flighty,” but most drank their own urine to survive. The following morning the castaways found a man floating on a piece of cabin. Many of the men climbed onto it so they could tip their lifeboat and empty it of water. Exhausted and hungry, the men rigged two masts out of pieces of the wreck, made sails out of life preservers’ coverings, and sailed the lifeboat northeast. Later that day, they met up with another lifeboat, occupied by the third mate and nine other men. Neither Allen nor Harris (who gave statements to the press) identified the third mate by name. They said the third mate gave them a handful of crackers but with their throats swollen from immense thirst, they could not swallow. The lifeboats parted ways with Finger and Allen’s boat taking a more northerly direction where it was spotted on the evening of October 5 by the Fleetwing, a Norwegian bark en route from British Honduras to Liverpool. The crew took the wearied survivors aboard where they remained for over a day before being transferred to the schooner S.J. Waring. Their skin blistered and peeling from the sun, the eight crew members and two passengers survived the Evening Star’s violent sinking and two days adrift on the open sea.

Survivor’s Accounts

As horrifying as the men’s experience was, Frank Girard’s was more grisly, though his accounts are slightly inconsistent. Originally Girard’s lifeboat took in 16 survivors, including Captain Knapp and third mate Thomas Fitzpatrick. The fourth time their boat capsized, Knapp was lost when a piece of driftwood smashed him in the forehead and he disappeared beneath the waves. Like the other lifeboat, no women were in Girard’s, which eventually held ten men: five sailors and five passengers.

Although Allen and Harris both recounted to the press that they met the lifeboat of the third mate (presumably Fitzpatrick), in Girard’s lengthy accounts he never mentions running into the other lifeboat. Furthermore, Girard stated that his boat had no food or water. If in fact it had, given the crew members’ behavior, it is unlikely that they would have shared their meager supplies. According to newspapers, however, sailors on Girard’s lifeboat stated that on their second night at least ten small flying fish landed in the boat, which everyone quickly devoured. Further, Allen and Harris stated the third mate’s boat contained ten men, so it seems likely that the encounter between the two lifeboats took place. It is unclear why Girard omitted it.

The second day, Girard recounted, included the laborious task of bailing out the boat. Everyone got into the water and tipped the boat up on its side while one after another boarded. They gathered up the corners of an old oilskin jacket and scooped out the water a few inches at a time. The first passenger also died, a Frenchman from the opera company who laid down and never got up. Girard said the remaining passengers died the same way. Drinking seawater made them delirious, destroyed their “vitality,” and allowed death to come quickly and quietly. Girard followed the crew members’ example and drank his own urine. He later chronicled the crew’s routine when a passenger died: rob him and toss him overboard to be devoured by sharks that followed closely behind.

On the morning of October 7, the boat arrived at Fernandina, Florida, carrying two passengers who had died just hours before: a Mr. Dixon, a high Mason from Philadelphia (whom Girard claimed had his jewelry stolen by the sailors before Girard got it returned to Dixon’s family) and a Billie Dawson. In one account, Girard stated on the afternoon of the fourth day, the third passenger died and was tossed overboard, and that the fourth and final other passenger died slightly before they reached land and was kept aboard to be buried. However, other reports claim that a recent West Point graduate, Lieutenant W. P. Dixon, was one of the passengers who died on the lifeboat and was dropped in the sea and that a passenger named McKimm (who is not on the passenger list) was left in the boat. It is unclear which Dixon died in the lifeboat right before it reached shore, or was left alive in the lifeboat and died while others searched for help. Many newspapers stated Girard’s lifeboat arrived with Girard, five crewmembers and the bodies of two passengers.

It is possible that being the only surviving passenger, Girard exaggerated the crew’s bad conduct while magnifying his “heroic” benevolence, heightening the drama of his already harrowing experience. With no other passengers to contradict him, Girard could cast himself in any light he chose since he remained the only living passenger to tell the tale.

A third lifeboat was picked up by the schooner Morning Star from Cardénas, Cuba. It carried pilot James W. Lyon, two other crew members, and four passengers, including two women, Minnie Taylor and Mollie (or Nellie) Wilson, presumably a singer and a prostitute. They had lost four other passengers (including one woman) who, crazed from lack of food and water, jumped into the sea.

The most harrowing account came from the final surviving lifeboat, manned by second mate William Goldie. Newspapers around the country already announced that all survivors had been found, so Goldie’s story is rarely included in the final account. Unlike the other lifeboats, Goldie’s was completely filled with passengers, and only had a small board for navigation. During the first two days the boat repeatedly capsized, leaving nine passengers alive, five men and four women. One of the male passengers gave Goldie his shirt, who rigged a sail by putting a cross bar through the arms and lashing it to a vertical pole. One male and female passenger died as they drifted and were tossed overboard. The rest of the men, and one of the women, insane from hunger and thirst, threw themselves overboard. This left only Goldie, 16-year old Rosa Howard (believed to be Rosa Burns), and 20-year old Annie Norton, both from New York and both likely prostitutes. Goldie described the women to the New York Herald as “heroines” saying they were “brave, gentle, lady-like, uncomplaining, able to obey directions, desirous of assisting themselves and others to the utmost.” On October 8, their fifth day at sea, a slight rain fell. Goldie gathered a small amount of water in one of the women’s petticoats for them to share. Shortly thereafter, they reached the Florida coast near the St. Johns River. The young women, dressed only in their chemises, sat in the bottom of the boat quietly with their hands clasped on their knees. The lifeboat got through two waves in the breaking surf but capsized on the third. Goldie, ecstatic that his feet touched the bottom, made his way to shore, shouting for the women to follow. In their feeble condition, however, the women, yards away from land, were swept away by the undertow. Norton’s body was found that evening by two fishermen and buried the next morning, while Howard’s body was almost completely devoured by sharks, with nothing remaining but her “perfectly formed” foot. Her remains were buried in a nearby plot with sailors and Civil War soldiers. Goldie walked 12 miles through a swamp until he found help.

Although the survivors lists are incomplete (some simply list “servant” or “lady”) and have many misspellings, complicated by many women travelling under assumed names, it is estimated that 24 people survived the Evening Star’s sinking: seven passengers (less than 4 percent) and seventeen crewmen (almost 30 percent). Girard told the Prairie Farmer that it was as “clear as the noonday sun” why so many sailors and so few passengers were saved. However, if all of the passengers who originally made it into lifeboats survived, the total number of passengers saved would have been 24. Regardless of their possible malevolence, perhaps the crew members were better equipped to handle the miseries of being stranded at sea, although that soon came under investigation.

A monument in New Orleans’ St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 notes that architect James Gallier and his wife Catherine Maria Robinson were “lost in the steamer Evening Star which foundered on the voyage from New York to New Orleans, October 3, 1866.” There was no burial beneath this marker since the Galliers’ bodies were never recovered. A portrait of James Gallier, Sr., is attributed to Charles Octavius Cole. Courtesy Louisiana State Museum

Sobs and “Scabs”

The sinking of the Evening Star dominated headlines. With scarcely any details for the first few days, people anxiously crowded the office of the NYMSC, hoping that a telegram might arrive with joyful news. According to the New York Times, it was the “absorbing topic of conversation everywhere,” intensified by the fact that most of the fatalities were women, even if they were “victims of a wicked life.” A French opera troupe in New York held a Mass at the French Catholic church for the repose of the artists’ souls. In Paris, the Dramatic Artists’ Association held a mass at St. Roch attended by its members and the families of many of the victims. The widow of Mr. Clarence was carried out of the church, sobbing in hysteria. The father of Miss Du Mery, the young woman believed to have hung onto the side of the lifeboat for hours, fainted from excessive grief. Compounding the tragedy, many had no means to take care of themselves and were plunged into poverty with the death of their family members. One elderly lady was caring for her grandchildren and suddenly had no means to care for them.

In New Orleans, the feeling of despair was equivalent, but there were also practical concerns — the tragedy left holes in the city’s brothels, theaters and opera that needed to be filled. The New Orleans Times stated “scarcely a single place of amusement escaped loss” from the tragedy. Flora Burdell and Jennie King’s fine homes and furnishings were sold at auction. The prismatic sign for the Varieties Theatre was lost among the steamship’s cargo. The French Opera House hosted a benefit for Paul Alhaiza, as a “substantial token of their deep sympathy.” The tickets prices were high — no less than $5 — but the Picayune reported that the “fashionable portion” of the Creole and French populations and a “fair quota” of American and German citizens filled the theater. The owners appointed Alhaiza as manager and benefit concerts enabled the opera house to remain open until a new opera company could be recruited. The Academy of Music ran repeat performances, and actors, musicians and magicians continued their productions until another troupe was found.

But while New Orleans focused on saving its forms of entertainment, preachers across the country focused on saving souls. Many reverends used the sinking (particularly the loss of the “fallen angels”) as a lesson to those who contemplated veering from God’s path, claiming the steamship was destined to sink since it was “loaded down with iniquity.” Reverend J. Sanford Holme of the Fifty-Second Baptist Church in New York preached that despite the intellect and power of man, he was “insignificant when brought into comparison with God.” Insignificant or not, multiple authorities sought the intellect of men when deciding where and upon whom the blame for the steamship’s sinking should be placed.

Many newspapers republished the reports of Wimpenny’s death as a fateful premonition. It was also revealed that the NYMSC was in the midst of a labor dispute with the Steam Fireman’s and Coal Passer’s Association. The workmen demanded $50 to $60 a month, but since the NYMSC refused to pay those wages, no association man would sail on the ship. As a result, the company hired men at lower wages with some just working for their passage to New Orleans and with virtually no sailing experience. James Byrne, the secretary of the Association, claimed it was a “notorious fact” that chiefly foreigners from Ireland and Germany, many of whom could not speak English, manned the Evening Star. An editorial in The New York Times agreed, stating that it was impossible for skilled Americans to compete with the foreigners’ low wages and that “no service was ever so disgraced by a set of irresponsible land lubbers as is the mercantile marine of the United States today.”

The Treasury Department ordered an official investigation into the Evening Star’s sinking. Captain W. M. Mew, who was in charge of the administration of steamship laws, supervised. Mew concluded the steamship was sound, finding the main cause to be captain error and an insufficient number of crew. Mew argued that Knapp, having “strong premonitions” of the storm, kept on a direct course, encountering the full brunt of the storm head on. If the ship had headed west early in the afternoon of October 2, it might have escaped the hurricane’s full fury. Furthermore, if the ship retained the customary carpenter to repair the breaches, perhaps disaster could have been averted. Mew supposed that with such a weak crew at his disposal, Knapp must have felt “comparatively helpless.” Doubtless, the passengers felt the same.

Despite the magnitude and scope of the tragedy, there are few remaining tributes to the Evening Star. A few weeks after the sinking, a poem entitled “Stella” was published about one of the women who came from the large group of the “frail sisterhood.” That same year, Henry C. Work wrote a song called “When the Evening Star Went Down”: Sail’d ever a ship from her quay so heavily ladened as she; With folly and fame, with home and shame, vanity with mirth and glee?

In New Orleans, the disaster is marked on James Gallier’s cenotaph at St. Louis Cemetery No. 3, designed by his son to honor his father and stepmother. Indeed, the loss was felt from high society families, to poor and modest families, to the “families” bound by contract on stage or in houses of ill repute. The Evening Star, so emblematic of class and society in its day, ultimately served as a reminder that fate and death make no such divisions.

—–

Sally Asher is a New Orleans-based writer and photographer. She has master’s degrees in English and Liberal Arts from Tulane University. She is the author of Hope and New Orleans: A History of Crescent City Street Names (2014) and Stories from the St. Louis Cemeteries of New Orleans, debuting in October 2015.For more information, visit www.sallyasherarts.com.