A Final Album but No Swan Song

Published: September 1, 2016

Last Updated: August 23, 2018

Allen Toussaint’s Enduring Influence

by Ben Sandmel

Over the course of his six-decade career, Allen Toussaint (1938–2015) garnered acclaim as a songwriter, producer, arranger, pianist, bandleader, background singer, lead vocalist, and solo performer. “Renaissance man” is not a term to be used loosely, but it aptly applies in the case of the deft, imaginative Toussaint, who attained iconic stature within the top-tier context of global popular music, far beyond his hometown of New Orleans. Toussaint earned his accolades as a major architect of second and third generation New Orleans rhythm & blues. His masterful touch is heard on the hits of Irma Thomas (“It’s Raining”), Ernie K-Doe (“Mother-In-Law”), Lee Dorsey (“Ride Your Pony”), Art Neville (“All These Things”) and Dr. John (“Right Place, Wrong Time”), among many others. Successful interpreters of Toussaint’s songs who followed from afar include Glen Campbell (“Southern Nights”), Boz Scaggs (“What Do You Want The Girl To Do?”) and the Pointer Sisters (“Yes We Can Can”). In addition, Toussaint wrote instrumental pop-jazz hits for trumpeters Al Hirt (“Java”) and Herb Alpert (“Whipped Cream”). When Toussaint opened his own studio in 1973, major stars flocked to New Orleans to record there, resulting in such hits as in Labelle’s “Lady Marmalade,” which Toussaint produced, and “Listen To What The Man Said” by Paul McCartney and Wings.

In 2009 Toussaint surprised many followers by departing from R&B on an album entitled The Bright Mississippi. Produced by Joe Henry — who had paired Toussaint with Elvis Costello on The River In Reverse, shortly after Hurricane Katrina — The Bright Mississippi focused on traditional New Orleans jazz, à la Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, and compositions by jazz greats from elsewhere such as Duke Ellington, Django Reinhardt and Thelonious Monk. Toussaint had heard hometown jazz while growing up, especially as played by second line bands, but it did not influence him as significantly as might be expected. His early awareness of Morton was, in fact, minimal.

“I wasn’t really up on Jelly Roll until much later in my life,” Toussaint said in a 2009 interview at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. “Of course he was strong until there was elements of him, second or third-hand, in all of us.” (By “all of us” Toussaint meant the fellow New Orleans R&B pianists of his generation.) “I guess I vicariously got whatever came through,” he continued, and Toussaint did record a Morton song on The Bright Mississippi. “But,” he concluded, “I was so busy trying to catch up with Professor Longhair that I didn’t pay much attention.”

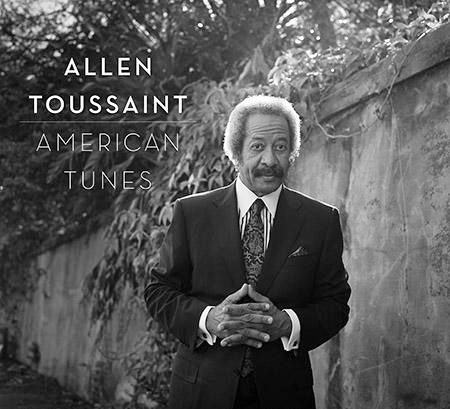

American Tunes

Allen Toussaint

www.Nonesuch.com

A new album by Allen Toussaint, the posthumous release American Tunes (Nonesuch) produced by Joe Henry, melds the late pianist’s passion for Professor Longhair with a continuation of his late-career embrace of jazz. Toussaint’s sudden death last November shocked his legions of admirers, both in New Orleans and throughout the global village of Louisiana-culture zealots. He had been playing and singing in peak form, and appeared to be in robust health. As Toussaint’s absence remains sadly conspicuous, many who mourn his passing may be pleased to know that the last project he completed is, in its best moments, profoundly brilliant.

American Tunes is divided between solo pieces and collaborations with renowned musicians including the guitarists Bill Frissell and Greg Liesz, and the saxophonist Charles Lloyd. They play beautifully, with exquisite, unhurried luxuriance, and their solos underscore Toussaint’s lesser-known skill as a sensitive accompanist in a small jazz band setting. Toussaint also demonstrates this facet of his talent when backing guest vocalist Rhiannon Giddens. But it is Toussaint’s solo explorations of Professor Longhair classics that provide the album’s most adventurous and stimulating moments. These interpretations are not faithful tributes to the Longhair idiom with all its rough-hewn charm. Toussaint ignores the penchant of the man known as “Fess” for jumping time by dropping or adding beats at random. He also eschews Fess’ charmingly eccentric singing — with its warbles, whistles, and idiosyncratic scatting — by playing Fess’s songs as instrumentals that significantly rework the originals in terms of melody and harmony.

Toussaint’s solo explorations of Professor Longhair classics provide the album’s most adventurous and stimulating moments.

On the Mardi Gras anthem “Big Chief” (a song popularized by Fess, but written by Earl King), Toussaint reprises the forceful funk intro that’s familiar to virtually all New Orleanians. Then he unexpectedly floats into a soft, plaintive passage. This ethereal moment is followed by an ornate and stormy quotation from Frederic Chopin’s “C-Minor Prelude,” before Toussaint abruptly ends the song with a Cuban “cha-cha-cha” triplet. These explorations give the listener startling new ways to hear and conceive of Professor Longhair’s music. Toussaint’s take on “Hey Little Girl” bears only passing resemblance to the Fess original, but curiously includes the well-known rhythmic riffs from “Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” as if the two titles were interchangeable. When Toussaint actually does play “Mardi Gras In New Orleans,” he gives the Carnival classic a significantly slower tempo than usual and uses that pace for delicate improvisations that reference, among other compositions, the wistful “Berceuse” by Louis Moreau Gottschalk. A classical composer, virtuoso pianist, and fellow New Orleanian, Gottschalk became a mega-star in the 1860s, in large part for his florid explorations of Afro-Caribbean folk-rooted sources.

As producer Joe Henry explained to the music journalist Steve Hochman, in the online magazine Music Aficionado, Toussaint felt compelled to present Fess in the context of such ostensibly distant milieux because: “[Allen] wanted people to recognize Longhair as a composer of significance, not just a good-time entertainer.” At the same time, Toussaint had doubts about his own worthiness to stretch out in certain new directions. Henry told Hochman that “[Allen] said… ‘I don’t know if I’m allowed to do this or not. I’m not allowed to funkify Gottschalk.’ I said, ‘Of course you are! No artist thinks that their art is unapproachable.’” Toussaint’s granting himself such permission manifests in a glorious rendition of Gottschalk’s “Danza,” featuring a piano duet with the like-minded Van Dyke Parks, accompanied by the cellist Cameron Stone. Parks has been revered in the music industry since the ‘60s as a sui generis composer, arranger, producer and pianist. His association with Toussaint goes back to 1975, when the two co-wrote some arrangements for Toussaint’s solo album Southern Nights.

Gulfstream

Roddy Romero and the Hub-City All-Stars

Octavia

www.RoddieRomero.com

American Tunes closes with a Paul Simon composition, “American Tune” which Toussaint sings with soulful understatement. It is his only vocal on this album. Simon and Toussaint were longstanding friends and mutual admirers with much in common. “American Tune” includes the line “And I dreamed I was dying…” To hear Toussaint sing these words, on his first release since his demise, is extremely jarring. In their grief, perhaps, some listeners have leapt to the conclusion that Toussaint chose this song based on a premonition of death. At the time of his passing, however, Toussaint was eagerly anticipating other projects and recording frequently at his home studio. Hopefully some of his unreleased material will appear before long, as will newly compiled reissues from his prolific, historic oeuvre.

Meanwhile Allen Toussaint’s songs continue to be recorded anew, most recently by two spirited bands whose music draws, in part, on the continuum of New Orleans R&B and swamp-pop. Gulfstream, by Roddie Romero and the Hub-City All-Stars (Octavia, www.RoddieRomero.com) kicks off with Toussaint’s great but lesser-known “My Baby Is The Real Thing.” On Golden Crown The Creole String Beans (www.creolestringbeans.com) cover the exuberant “Holy Cow,” which Toussaint wrote for his dear friend Lee Dorsey, as well as the haunting “How Could I Help But Love You,” first recorded by Aaron Neville. Both bands convincingly evoke the soundscape of 50 years ago while infusing this music with their own dynamic aesthetics, thus avoiding the dry tedium of verbatim reproductions. The most striking of these renditions is Romero’s less-is-more vocal on “I Hope,” by the great south Louisiana songwriter Bobby Charles. The versatile Romero can caress a lyric or rock out full-tilt — as heard on “Rock ‘N’ Roll & Soul Radio” — and he matches these singing skills with masterful, inspired solos on guitar and accordion alike. The presence of this latter instrument points up the inclusion of Cajun music and zydeco in Romero’s repertoire. The Creole String Beans, from New Orleans, capture a lot of this French Louisiana feel, too, albeit sans squeezebox. Bassist Rob Savoy was a founding member of the Bluerunners, a Lafayette-based “Cajun cow-punk” band that attained national-level success in the early ‘90s. The two groups’ commonality is further underscored in that saxophonist Derek Huston is a member of both.

Golden Crown

The Creole String Beans

Independent

www.creolestringbeans.com

Along with reprising classics, both bands perform original material. Romero and keyboardist Eric Adcock are the principal songwriters for the Hub City All-Stars. Rick Olivier, guitarist and main vocalist for the Creole Strings, also shines in that band for such compositions as “Golden Crown.”

“…I dug me a moat for the savages at the gate,

Pulled up the bridge, don’t let princess escape.

A man’s home is his castle but being king is such a hassle,

Another dog impounded with a golden crown.

All my subjects are gathered round, waiting for a word from me,

noblesse oblige, I’m on my knees, begging for democracy…”

Allen Toussaint — who came up with such clever titles as “Whoever’s Thrillin’ You Is Killin’ Me,” and “Who’s Gonna Help Brother Get Further?” — would appreciate Olivier’s nimble word-play. And he would also be pleased to know that his influence remains absolutely undiminished, as it will for generations to come.

—–

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist, and producer and is the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his latest book, Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012.