Book Excerpt

The Corps Takes the Teche

The Army Corp of Engineers, showboats, and the designing of a Louisiana waterway

Published: March 1, 2017

Last Updated: April 29, 2019

Courtesy of Shane Bernard

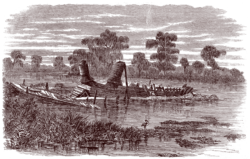

Confederate gunboat C.S.S. Cotton, scuttled in Bayou Teche near Calumet and Ricohoc, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 14, 1863.

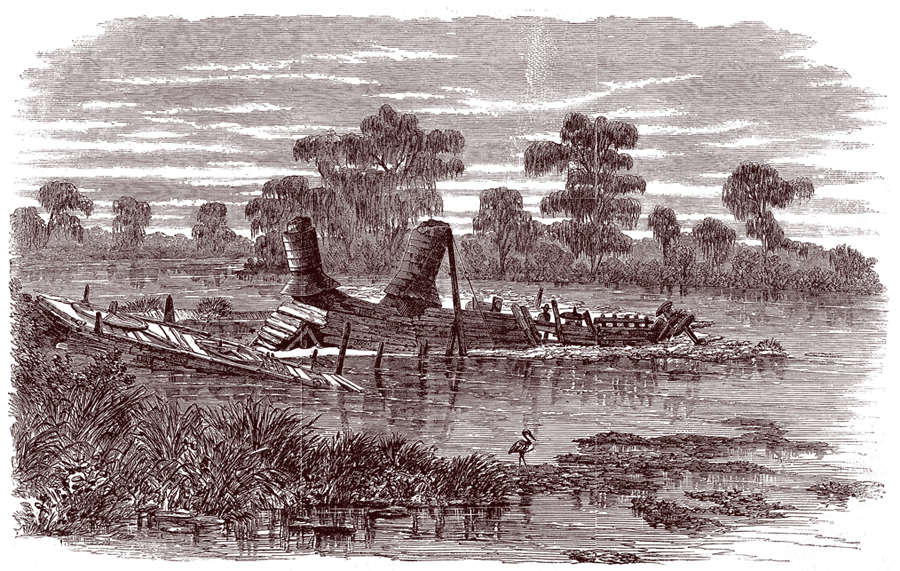

Because of these complaints by Trinidad and others who depended on the waterway for their livelihoods, the state of Louisiana set aside $30,000 in 1869 “for removing obstructions in navigation in the Bayou Teche.” On completion of this project, however, Trinidad expressed only displeasure, charging that “personal greed absorbed all of the state appropriation.” He possibly felt relief when in 1870 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took over clearing the Teche. Established in 1802, the Corps directed the upkeep of America’s navigable waterways. Indeed, no navigable body of water, including the Teche, could be dredged, dammed, widened, or bridged without approval from the Corps and its chief administrator, the U.S. Secretary of War. Although the Corps neglected the Teche prior to the Civil War, it now invoked its mandate to oversee the waterway. Receiving over $17,000 in congressional funding, the Corps sent civil engineer William D. Duke to survey the Teche in May 1870 as a prelude to clearing it. As he paddled a skiff the seventy-five miles from St. Martinsville to the bayou’s mouth at Pattersonville, Duke took frequent cross sections and soundings to create a highly detailed thirty-two-sheet map of the Teche. On this map he recorded every stump, log, and sunken vessel that he regarded as a menace to navigation.

Map of Bayou Teche showing obstructions, by steamboat captain E. B. Trinidad, ca. 1868-69, from the National Archives and Records Administration. Reproduction courtesy of Grevemberg House Museum, Franklin, LA.

“The greatest obstruction” between St. Martinsville and New Iberia, Duke informed the Corps, “is the heavy undergrowth, trees & stumps on both sides, extending in and over the bayou almost intersecting in an unbroken line.” He found the lower reaches of the Teche in similar condition, “very much obstructed by innumerable logs & stumps [and] over-hanging live oaks.” There, closer to the bayou’s mouth, he also encountered many sunken vessels, including the gunboat Diana, “with a portion of her machinery visible—her shaft & flanges, cylinders & old iron.” Farther downstream Duke located the remains of the gunboat Cotton, which, he noted, “lies nearly at right angles with the stream . . . her stern 6’ below low water, [and] her machinery, which is visible, consists of wheel shafts & flanges, cylinders & throttle valves. . . ” Duke’s recommendation for handling these wrecks expressed no sentimentality or interest in historical preservation: the vessels, he stated, should be “hauled out or blown up.”

On completion of Duke’s survey the Corps commissioned another civilian, Daniel M. Kingsbury, to clear the waterway. In February 1871 Kingsbury and his detail of twelve laborers—many of whom, he grumbled, dissipated themselves in drinking and brawling—ascended the waterway in a wrecking flat built especially for the project. Designed much like a snag boat, the wrecking flat boasted a variety of tools for handling unwieldy, possibly submerged obstructions. These tools included grapnel and timber hooks, crowbars, sling chains, ropes, a manual winch, and a twenty-one-foot derrick for lifting heavy loads. Kingsbury christened the flat the Major Howell, after his superior, Charles W. Howell of the Corps of Engineers. Regretting this obsequious choice, Kingsbury shortly rechristened the vessel the Bayou Teche.

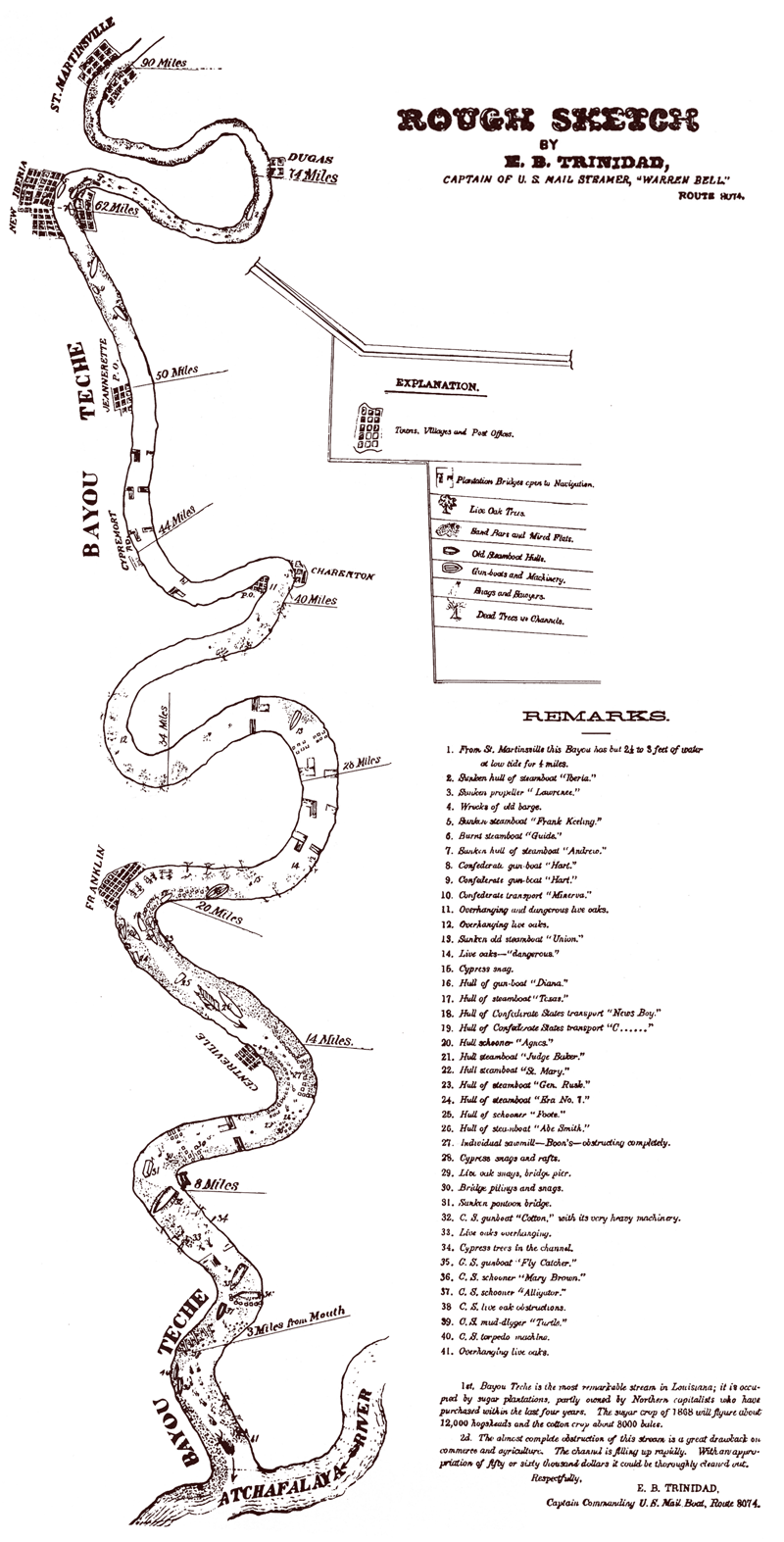

Up and down the waterway Kingsbury and his men removed logs, snags, roots, old pilings, even entire trees growing along the banks—anything that might impede steamboats plying the Teche. The most grueling task, however, would be the removal of sixteen sunken vessels. These included, among others, the Flycatcher, Minerva, Gossamer, Rob Roy, Iberia, and the gunboats Diana, Cotton, and Stevens. With their hefty timbers, dense machinery, and thick iron plates, the gunboats in particular resisted the wrecking crew’s exertions. The ironclads would have to be blasted, just as Duke had recommended earlier, and removed in fragments. “I have made one blast today on the wreck. . . ,” Kingsbury reported to Howell regarding the Cotton. “The charge was about 75 lbs. powder. It was quite effectual, tearing away a large portion of the front part of the wreck. I shall make one or two more blasts this afternoon.”

The Cotton proved sturdier than expected and Kingsbury shortly confessed, “I did not think I should have had near the difficulty I have had in destroying her.” He reluctantly called in professional divers from New Orleans, who planted waterproof gunpowder charges at weak spots in the wreckage. “We have made 8 blasts since the 9th . . . ,” he informed Howell. “One of the blasts[,] the can contained 263 lbs. powder, [and] was placed at the hull directly under her port engine. I think it was very effectual, as large masses of the machinery & timber were thrown high into the air.” But, he noted, “[N]early all her timber, as it is blown to pieces, immediately sinks, which will take considerable time for me to remove.” Finally, the Cotton began to give way. Reclaiming some of her iron, Kingsbury sold it as scrap to fund modifications to the wrecking flat. One intriguing iron artifact may have escaped the melting furnace. “Yesterday we removed large masses of timber from the wreck,” Kingsbury recorded. “Among the mass was an iron cannon, which fell off the mass of timber in hoisting the same.”

Steamboat crew members and passengers lauded the improvements, even as Kingsbury and his men toiled away on the unfinished job. “The steamboat Warren Belle yesterday evening passed up the channel made on the left bank of the bayou going up,” Kingsbury told the Corps. “She had quite a large number of passengers on board. They appeared much pleased in seeing the obstructions removed thus far, the ladies and gentlemen waving their handkerchiefs & their hats, accompanied with a pistol salute.” By project’s end in late 1871, Kingsbury had removed from the Teche, among other detritus, sixteen wrecks (three partially); eighty-two bridge pilings; twenty-one “dangerous snags”; thirty-eight overhanging trees; one hundred six limbs; and a raft of one hundred ninety-one sunken “large live-oak logs.” Captain Trinidad gleefully wrote Major Howell, “It is a pleasant duty to acknowledge that the work done, under your instructions, by Captain Kingsbury is complete in every respect, and [has] restored once more that important stream, Bayou Teche, to navigation.”

Congress authorized more improvements to the bayou in the River and Harbor Act of March 3, 1879, and in 1880 and 1881 it apportioned $26,000 specifically to improve the Teche north of St. Martinsville. The water level in that stretch often ran extremely low, as the Corps observed in 1880: “[T]here has not been sufficient water for navigation [in the uppermost Teche] within the memory of the oldest inhabitants, except during the extreme high-water of 1874.” Another army engineer echoed this account, noting, “The upper 6 miles of the . . . Teche is but little more than a gully; its banks are very steep, heavily timbered, and . . . [d]uring a large portion of each year this part of the bed of the bayou has no water in it except in little pools; in fact this portion of the stream becomes dry.”

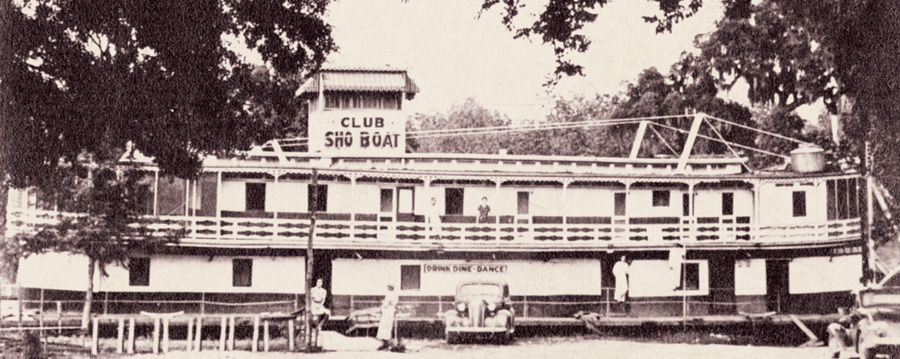

The Club Sho Boat, a converted riverboat, docked at New Iberia, ca. 1940. Courtesy of Shane Bernard and Angelle-Leigh Breaux

Still, even the high-water season could leave the bayou dry above St. Martinsville. “[T]here was not enough water in the Upper Teche to permit my examination to be made in a perogue [pirogue],” lamented an army engineer in December 1886, about a month into the high-water season. Moreover, a gauntlet of obstacles would have barred navigation to the head of the bayou. Another army engineer thus described the four miles of the Teche below Port Barre as “filled by standing trees, which grow even down to the bottom of it, and with overhanging trees, bushes, and logs and fallen trees. . . .”

Motivated by appeals from local and state politicians, the Corps resolved in the early 1880s to open the entire upper Teche to commercial traffic. If achieved, the bayou could be used not only by those living on its banks, but by others on the Courtableau and its tributaries who desired a less turbulent path to New Orleans than the wild, sometimes log-choked Atchafalaya River. The Corps would open the upper Teche, it proposed, not so much by deepening its channel through dredging, but by building a series of locks and dams to raise the water level on the bayou. The project, asserted the Corps, would require three sets of locks and dams—one below and two above St. Martinsville. The estimated cost: nearly $90,000, or more than three times the original budget fixed by Congress for Teche improvements. This estimate swelled to over $135,000 once it became clear the project would require dredge boats, derricks, and a small army of laborers for at least a year.

Showboats plied the Teche more frequently in the late 19th century, when these “floating palaces” ventured from their primary Mississippi River routes to find new audiences.

While the federal government mulled over the expense of these proposed locks and dams, the Corps pushed forward with less costly improvements, removing “overhanging trees, logs, snags, and other obstructions” from the thirty-eight miles of bayou between St. Martinsville and Leonville. Four years later the Corps cleared the remaining eleven miles to Port Barre. During an ideal high-water month, estimated an army engineer, a steamboat 175 feet long by 30 feet wide could now ascend the Teche to within ten miles of Port Barre—to within eight miles if not for a static bridge blocking the route.

Ironically, the Corps of Engineers’ improvements came just as steamboat traffic on the Teche, as elsewhere, entered a long, slow decline. During the decade and a half prior to the Civil War, steamboats from Bayou Teche arrived at New Orleans an average of 115 times per year. By the early to mid-1880s, however, the average had fallen to a mere thirty-seven arrivals per year. This precipitous drop stemmed from competition with a new mode of transportation, one that threatened to make Bayou Teche obsolete as a conduit for moving people, sugar, cotton, livestock, merchandise, and other things once consigned solely to waterborne shipping. That new means of transportation was the railroad.

In 1857 the New Orleans, Opelousas, and Great Western Railroad connected New Orleans to Brashear City, only about 10.5 miles by water from the mouth of the Teche. Planning to extend this line northwest along the bayou, the railroad company installed a graded rail bed to New Iberia. From there the bed veered northwest from the Teche toward Vermilionville. The Civil War halted the laying of track beyond Brashear City, but construction resumed after the conflict. The railroad—renamed Morgan’s Louisiana and Texas Railroad in homage to its owner, shipping magnate Charles Morgan—finally reached New Iberia in 1879. By next summer the railroad connected New Iberia, Jeanerette, Franklin, Centreville, and Pattersonville to such seemingly distant cities as New Orleans and Houston. By 1901 additional rails extended along the Teche as far upstream as Arnaudville.

Postcard image of the steamboat Amy Hewes on the Teche, one of the last steamboats to ply the waterway, ca. 1935. Courtesy of Shane Bernard

Predictably, the railroad disrupted the Teche Country’s venerable steamboat industry, which at the time consisted of the People’s Independent Teche and Atchafalaya Line, Pharr Line Teche Steamers, and the New Orleans and Bayou Teche Packet Company, not to mention any number of itinerant tramp steamers. To the dismay of these steamboat operators, the railroad captured about ninety percent of the bayou’s shipping business within six years of its appearance—even while charging about fifteen percent more than steamboats per ton of freight. Planters opted for the higher rate, surmised the Corps of Engineers, because the sooner produce reached market, the sooner they received payment. For instance, a train could travel the eighty-seven miles of track between Pattersonville and New Orleans in under five hours. A steamboat, however, took five days to make the same journey via a circuitous, sometimes hazardous route covering over 300 miles—the distance to New Orleans by water since 1866, when Iberville Parish authorities dammed the shorter Bayou Plaquemine route as a flood control measure. (It did not help the Teche steamboat trade when the Pharr Line, hoping to stave off its own demise, colluded with Morgan’s railroad to destroy its rival steamer lines.)

Some of the old steamers, however, found new utility moving showboats—which, contrary to their popular image as self-propelled theaters, were actually unpowered barges that relied on smaller pushboats for motion. Showboats had appeared on the Teche as early as the 1840s, when a female promoter named Houston visited the bayou with her “large boat fitted up for the exhibition of wax figures and theatrical performances, and also for the sale of goods. . . ” Showboats plied the Teche more frequently in the late nineteenth century, when these “floating palaces,” as they often were billed, ventured from their primary Mississippi River routes to find new audiences. As one showboat historian has observed, the late-nineteenth-century vessels “penetrated deep into the Bayou Teche country . . . a veritable gold coast for the showboat.”

Blowing their whistles, striking up their calliopes, and beaming their searchlights at night, showboats ascended the Teche as far as St. Martinsville and sometimes ventured even farther upstream. In the 1840s, for example, Ms. Houston’s vessel entertained above St. Martinsville; and in spring 1886 the steamboat Hattie Bliss carried a “theatrical troup” [sic]—probably “DeVere’s Carnival of Novelties and Mastodon Dog Circus,” supported by the “Rex Silver Cornet Band”—above St. Martinsville to reach Arnaudville. But wherever showboats moored on the Teche, they attracted throngs of paying locals who relished vaudeville routines and the period’s ever-popular melodramas. As a St. Martinsville native recalled, “[T]he ship was primitive, the benches uncomfortable, the red velvet curtain shabby. . . . [But a]s the curtain fell, a happy bedlam broke loose in the audience. They . . . did not want this thrilling entertainment to end.”

In the early 1900s the Army Corps of Engineers oversaw two improvements that revived hope for the Teche steamboat trade. First, in 1909 the Corps replaced the Iberville Parish dam on Bayou Plaquemine with a lock, restoring this once popular navigational link between the Atchafalaya and the Mississippi. Significantly, this project reduced the traveling distance between the Teche and New Orleans by 135 miles and made it possible to reach the city from New Iberia in only three days instead of five. Second, in 1913 the Corps finally built a lock and dam on Bayou Teche between New Iberia and St. Martinville—again, to raise the upper Teche’s water level for the benefit of steam navigation. Called Keystone Lock and Dam (after adjacent Keystone Plantation), this project traced its origin to the Corps’ proposal of over three decades earlier calling for three such structures on the bayou.

Related Entries:

Teche: A History of Louisiana’s Most Famous Bayou

By Shane K. Bernard

University Press of Mississippi

272 pp. (approx.), 6” x 9” $25.00

Congress had rejected that idea as extravagant, but it eventually approved construction of one lock and dam. A single facility, conceded the Corps, would not raise the Teche sufficiently to permit navigation to Port Barre. “Of these upper 19 miles of the Teche,” an engineer reported, “I believe it to be impracticable to improve the 4 or 5 miles immediately below Port Barre for steam navigation, except at an expense greatly in excess of any benefit to be derived from such improvement.” In the end, the Teche’s uppermost reaches would not be opened to navigation until 1920, when a private business, the Atchafalaya-Teche-Vermilion Company, dredged the upper bayou to Port Barre. The company also excavated Ruth Canal between the Teche and the Vermilion River. (The purpose of these related projects was not to assist navigation, but to irrigate rice farms along those waterways.)

Despite congressional approval, the Keystone project had remained in limbo until passage of the River and Harbor Act of March 2, 1907. In that bill Congress authorized the Corps to secure “a 6-foot navigation to Arnaudville . . . at an estimated cost of $111,000, by dredging, removal of snags, etc., and construction of a lock” (emphasis added). To a twelve-acre tract at Keystone Plantation the Corps now brought in steel from Pittsburgh and Boston, gravel and sand from St. Louis and nearby Petite Anse Island (by then renamed Avery Island), and stone, timber, and cement from New Orleans. To claim additional water for the Teche above the dam, the Corps built a smaller dam on Bayou Fuselier and expanded a pre-existing channel, known as Keystone Canal, to divert water from Spanish Lake.

In summer 1913 the Corps completed major construction on the project and opened it for operation—only to find demand for the lock surprisingly lower than expected. Engineers dubiously blamed the lack of interest on World War I and its impact on international shipping. In actuality, the amount of freight passing through Keystone Lock only dropped after the conflict and would not exceed wartime levels until the mid-1930s.

The underutilization of Keystone Lock stemmed from competition, not only from the railroad, but from two new inventions: the automobile (including the versatile motor truck) and the modern highway system. While state and parish governments had created a road along much of the Teche by 1840, it had been designed for foot, horse, and wagon. In the early twentieth century, however, it became clear that motorized traffic would soon become commonplace and that better roads had to be constructed. Underwritten by the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, the Federal Highway Act of 1921, and private boosters, a modern graveled road reached the Teche Country in the early 1920s. Passing through Patterson, Centerville, Franklin, Baldwin, Jeanerette, and New Iberia, the new highway on its extremes connected the bayou—strange as it may have seemed—to St. Augustine, Florida, and San Diego, California. Officials called the highway U.S. 90, though it was also known as the Southern National Highway and, more frequently, the Old Spanish Trail (all of which overlapped along the Teche with a segment of the Pershing Highway).

Printed with permission of the University Press of Mississippi.

Shane K. Bernard is historian and curator of the McIlhenny Company Archives at Avery Island, La. He is the author of several books, including Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues (1996), The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (2003), Tabasco: An Illustrated History (2007), and Cajuns and Their Acadian Ancestors: A Young Reader’s History (2008).