Foodways

Hot Biscuits

Al Copeland and the race for perfection at Popeyes

Published: June 1, 2017

Last Updated: July 6, 2022

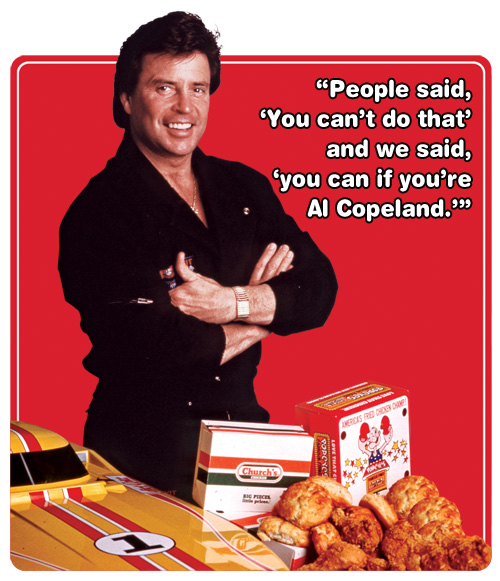

Courtesy of Kit Wohl

In early 1983, Copeland finally found what he was looking for: yet another secret recipe to pair with the closely guarded spice mix that made Popeyes fried chicken one of the defining culinary exports of modern Louisiana. The impact of Copeland’s discovery was immediate and dramatic: revenue spiked by 25 percent nationally. In the mercurial career of the legendary Louisiana businessman, the introduction of dense, crusted biscuits was a turning point. Like so much of his success, the windfall emanated from Copeland’s greatest gift: his drive.

“People think luck is involved,” he told Gus Weill of Louisiana Public Broadcasting in an April 1983 interview. “I just believe that you can’t settle for not making it.”

And that year, Copeland was most certainly making it. There were more than three hundred locations nationwide, including a Popeyes in Times Square. Sales for the previous year topped two hundred million dollars. The New Orleans native was in his prime, a self-made millionaire many times over. The biscuit boom led Copeland to rename his company “Popeyes Famous Chicken and Biscuits” and stoked his already sizable ambitions.

Copeland’s ascent was a Horatio Alger story tailored to south Louisiana in the ’70s and ’80s, made possible by decadent food played out during a decadent time. Born in 1944, he came of age during New Orleans’ postwar boom, a period when the city expanded to accommodate returning men in uniform, and their families—as well as an influx of African Americans from rural Louisiana. All sought the promise of a modern economy. Copeland’s family was by all measures blue collar, and he lived for a period in the St. Thomas Housing Projects. After graduating from Warren Easton High School, he took a job at the lunch counter inside a Schwegmann Giant Super Market. One day he noticed an especially motivated coworker who seemed to operate two steps faster than other employees. Why are you working so hard? Copeland asked.

“Because I’m better than you and I’m smarter than you, and you’ll never beat me,” the coworker responded.

According to family and friends, Copeland never forgot the soda jerk’s rebuff. He resolved to beat each and every competitor.

First, though, he’d need to taste failure.

Copeland’s brother Gilbert started Tastee Donuts, and Al joined him, operating four stores and making a decent living. But when a new chicken joint opened next door, Copeland took note. “We were a twenty-four-hour business,” he told Weill. “It was a little aggravating because they’d come in at eight o’clock and leave at three o’clock, and they’d do more volume than I did and make more money than I did.” In 1972 he opened a store called Chicken on the Run in Arabi. The short-lived operation failed in all ways but one: it taught Copeland the power of spicy. He’d experimented with several recipes, one spicy and one mild, and served them to a group of associates who convinced him to serve a milder flavor. “You’ll never sell it. Kids can’t have it, and it’s a family product,” they insisted. Copeland disagreed, but took the advice. The spicy chicken was billed as a side item that required a fifteen-minute wait. After seven months and an eleven-thousand-dollar loss, Copeland faced a choice: close and reopen as a donut shop, or gamble on spicy. He decided to take the risk, but wanted to rename his business. With a reopening just days away and a sign painter contracted, Copeland couldn’t make up his mind. He took his wife to see Gene Hackman in The French Connection. Playing a New York City detective, Hackman bursts into a barroom and shouts, “Everybody hit the wall! Popeye’s here.” Copeland called the sign painter with a name: Popeyes Famous Fried Chicken.

Copeland’s brother Gilbert started Tastee Donuts, and Al joined him, operating four stores and making a decent living. But when a new chicken joint opened next door, Copeland took note. “We were a twenty-four-hour business,” he told Weill. “It was a little aggravating because they’d come in at eight o’clock and leave at three o’clock, and they’d do more volume than I did and make more money than I did.” In 1972 he opened a store called Chicken on the Run in Arabi. The short-lived operation failed in all ways but one: it taught Copeland the power of spicy. He’d experimented with several recipes, one spicy and one mild, and served them to a group of associates who convinced him to serve a milder flavor. “You’ll never sell it. Kids can’t have it, and it’s a family product,” they insisted. Copeland disagreed, but took the advice. The spicy chicken was billed as a side item that required a fifteen-minute wait. After seven months and an eleven-thousand-dollar loss, Copeland faced a choice: close and reopen as a donut shop, or gamble on spicy. He decided to take the risk, but wanted to rename his business. With a reopening just days away and a sign painter contracted, Copeland couldn’t make up his mind. He took his wife to see Gene Hackman in The French Connection. Playing a New York City detective, Hackman bursts into a barroom and shouts, “Everybody hit the wall! Popeye’s here.” Copeland called the sign painter with a name: Popeyes Famous Fried Chicken.

He began turning a profit and opened a second restaurant on Williams Boulevard in Kenner in July 1973. By 1976, Popeyes had thirty-two locations and sold its first non-Louisiana franchise, a Pittsburgh location purchased by football star Franco Harris. Copeland told The Times-Picayune that his Canal Street location generated one million dollars in business annually. Popeyes was now going toe-to-toe with Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Aside from the spicy chicken, Popeyes had that essential ingredient for success: a unique brand. Lamar Berry began crafting advertising campaigns for Copeland during the company’s early years, eventually coming on board to as Chief Marketing Officer for most of two decades. Berry wrote the “Love that chicken from Popeyes” jingle for commercials that infused the product’s branding with New Orleans iconography. “Everything that we did was revolving around the New Orleans milieu into the fabric and identity of the Popeyes product,” says Berry.

The fusion of fast food and the Big Easy carried images of the French Quarter and the voice of Dr. John, who sang a popular version of the company jingle, into living rooms across the nation. Many American viewers’ introduction to the term “Cajun” was as a descriptor on a side order of Popeyes rice. Aside from the red beans and rice, the authenticity of the supposed Louisiana features of the Popeyes menu were debatable—but Copeland and Berry continued to craft advertisements that paired fried chicken with Mardi Gras and traditional jazz. Along with chef Paul Prudhomme, Copeland deserves credit as a pioneer in packaging Louisiana for national consumption.

In his hometown, Copeland established a reputation as a homegrown P. T. Barnum. The company celebrated its tenth anniversary by rolling its prices back to 1972 for a week. “There were traffic jams at every Popeyes,” says Kit Wohl, Copeland’s longtime publicist. “The floor broke in one store. That’s how to mess up a city really quick.” The traffic jams were just a preview of Copeland’s famous home Christmas lights display, an annual attraction that eventually brought him to the Louisiana Supreme Court to face off against his irritated neighbors in Metairie. His competitive streak drew him to professional powerboat racing, where he set speed records, brought national races to Lake Pontchartrain, and proudly operated the first “superboat,” a fifty-foot aluminum catamaran emblazoned with a pipe-smoking Popeye cartoon. “It’s a real turn-on for me,” he admitted at the time, but sales were never far from his mind; “While I’m campaigning [racing] the boat,” he pointed out, “I’m getting publicity for Popeye’s at the same time.”

A 1980 profile in The Times-Picayune proclaimed Copeland “pure New Orleans, the easy-going, fun-loving person found in dozens of bars, living it up.” Popeyes made waves by sponsoring annual Carnival celebrations in the Superdome. The line-up in 1980 included Willie Nelson, Jimmy Buffet, and Crystal Gayle. In 1982 the company produced one hundred thousand doubloons, a traditional Carnival parade “throw”; each was redeemable for two pieces of chicken. “We threw 100,000 and we redeemed 120,000,” notes Berry. “People said, ‘You can’t do that’ and we said, ‘you can if you’re Al Copeland.’”

“He had an amazing mind,” says Wohl. “A lot of it was street smarts and a really good gut—he understood what people wanted.” But by 1983, he also understood the business of fast food. To wit: he’d been plotting his biscuits strategy for several years.

“I’ve always been disappointed by the roll. It’s a standard roll. Half the people eat it, half the people throw it away, but the industry dictates that you should have a bread product,” Copeland told Weill. “Four years ago we started with biscuits, we built a little area where you could see the bakery effect happen. We were really successful, but I never was satisfied with the product.”

Again and again, he went back to the tasting lab with his chefs Gary Darling and Warren LeRuth. Company executives became the biscuit focus group. “Every time biscuits were tested, which was several times a day, they’d come up with a tray of biscuits and you’d smell those biscuits coming down the hall,” Wohl recalls. “Everyone on the seventh floor had gained ten or twenty pounds at least.”

The pressure wasn’t reserved for the beltlines of his employees, says Berry. “That was during a time when we were in a very competitive, trench-level warfare with Church’s and KFC, in markets where we were expanding throughout the country. We knew that a major weapon was going to be that biscuit. Al would not let it into the field. Every month that went by, it was not perfect for him. It finally got to a point where several of us, including [executive Vice President] Ron Lewis, who was basically president of the company, had meetings with Al where we were begging him.”

Finally the day came when Copeland gave the green light for the recipe’s rollout in New Orleans. Wohl remembers dropping off biscuits at local radio stations to create a buzz, only to have Copeland yet again pull the plug. “So we went into another few months of testing,” she says. “Make no mistake—it was his company, his taste buds, his decision.” A few weeks later, he was satisfied. The product, he crowed, was “dynamite.”

“Today it represents an average of 25 percent of sales,” he told Weill. “And I believe that’s the largest increase in the fast food business for a secondary item, ever, for anybody, McDonald’s, Burger King, anybody, as a single additional product to increase your business.” Ever the competitor, Copeland wanted the world to know that he, a self-made man from New Orleans, was taking on the titans of the fast-food industry.

By 1985 Popeyes had five hundred locations in the United States, making it a solid third in the race against Kentucky Fried Chicken and Church’s. The dizzying rate of expansion enflamed his will to win and contributed to his ill-fated decision to purchase Church’s in 1989; two years later, the company was bankrupt. But Copeland remained undaunted, continuing to reinvent his businesses until his passing in 2008. Available today at more than 2,000 Popeyes restaurants across the globe, Copeland’s biscuits remain as a monument to the insatiable drive of a brash, self-taught New Orleans legend.

Brian Boyles was formerly vice president of Content at the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.