Parish Spotlight

The Shreveport Water Works Museum

A North Louisiana site preserves engineering history

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

Photo by Maria Schmelz

The Shreveport Water Works Museum preserves the first facility to provide the city with clean drinking water and fire-fighting water pressure.

It was August 29, 1881, and the total monetary loss from that one catastrophic fire was eighteen thousand dollars (almost half a million dollars by today’s standards); the emotional toll on residents and business owners was beyond calculation. Sadly, this was not an uncommon calamity. The tight configuration of the mostly wooden buildings combined with a lack of running water or a pumping station left Shreveport’s firefighters ill-equipped to handle any escalating blaze.

Shreveport was in desperate need of a pressurized water system. The first mayor of Shreveport, Andrew Currie, was perhaps especially incentivized to meet this demand because he was not only heavily invested in property in and around the city but was also in the insurance business, and his company was frequently required to pay for the damages incurred by these uncontrolled fires.

It is a common but mistaken belief that the first water plant in Shreveport was constructed to diminish the spread of disease. In truth, the wealthier residents of Shreveport were not overly concerned about the occasional epidemic outbreak; such events did not occur every year, and when they did, those with financial means could leave town. Fire, on the other hand, posed a much bigger threat to major property owners and jeopardized the city’s very survival.

Shreveport was heavily indebted, so Currie began taking bids for a privately owned company to provide the city with a water system. In 1886, Samuel R. Bullock was awarded the franchise and, in just a year, the Shreveport Water Works Company was open for business.

Prior to the plant’s completion, the people of Shreveport were forced to drain rainwater from their rooftops into large uncovered cisterns for their water needs. Unfortunately, this method also resulted in an accumulation of dust and debris, and an unwelcome assortment of snakes, frogs, and other creepy-crawly creatures residing in the drinking water. Moreover, indoor toilets were all the rage in other parts of the nation, and Shreveport residents no longer wanted to be left out in the outhouse.

“Despite the fact that it was originally constructed to fight fires, Shreveporters went down to the office of the Shreveport Water Works Company and started signing up,” says Dale Ward, executive director of the McNeill Street Pumping Station Preservation Society. “They wanted indoor plumbing . . . enough of this bucket stuff!”

In 1917, the city bought the company from Bullock, and the plant became the McNeill Street Pumping Station. What started as a two-and-a-half-acre enterprise blossomed into six acres of cutting-edge water filtration, disinfection, and distribution, meeting the needs of the community for over a century.

The original structure is now the site of the Shreveport Water Works Museum, home of the very last active steam-powered pump in the United States. With a new main entrance at 142 North Common Street, the old pumping station holds the rare distinction of being both a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark and a National Historic Landmark.

Photo by Maria Schmelz

“Believe it or not, Shreveport had, in the early days, one of the best processes of cleaning water in the country,” says Kevin Haines, administrative assistant at the Shreveport Water Works Museum. “Filters were added on the property in 1890 at a time when fewer than ten percent of the nation filtered their water.”

A small model in the museum demonstrates the water filtration technique, a process Haines likens to the course of a large, lazy river. As the water pours through the many twists and turns of the basin, its flow is restricted, allowing sediment to sink to the bottom. The farther the water travels, the less sediment there is to be deposited—sure evidence that the water is being purified. This process was dramatically improved in 1914, when the company became one of the first to use liquid chlorine to further disinfect the water.

“Clean water is good,” says Kevin. “Healthy water is better.”

Cross Bayou, the original source of water for Shreveport, sits beside the plant, but demand quickly exceeded its supply. In 1911, water from the Red River was mixed into the basins, but this resulted in a muddy color and high salt content that many water drinkers found distasteful. After an underground pipeline was constructed in 1928 to ferry water from Cross Lake, the Red River supplement was terminated. For the next fifty-two years, all city water came from the McNeill Street Pumping Station, but eventually, “the little steam engine that could” just couldn’t keep up, and in 1980, the city shut down the plant entirely. The T. L. Amiss Water Treatment Plant now supplies Shreveport with water, using Cross Lake as its sole supply source.

Once closed, Shreveport’s original water facility fell into decline and disrepair, until the McNeill Street Pumping Station Preservation Society was formed to save both the historic building and the equipment that faithfully served the population for so many years. In the spring of 2007, the Shreveport Water Works Museum opened to provide visitors with a fascinating and detailed look at how water starts in the bayou and ends up in our homes.

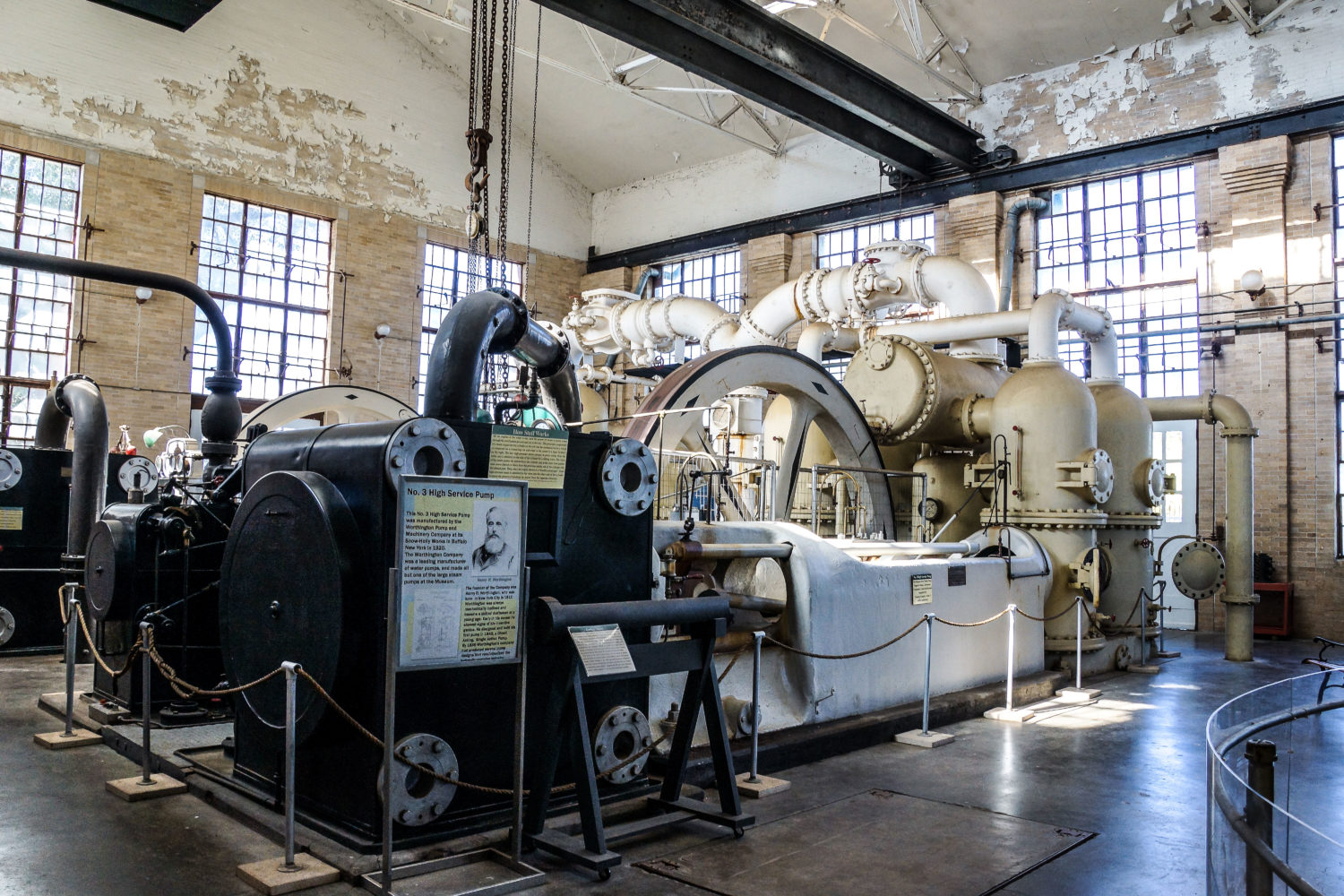

An outing to the facility includes a visit to the boiler room, settling basins, and filtration systems; a viewing of numerous captivating photographs; and many entertaining hands-on activities. However, the Main Pump Room—the core of the operation, where the water completes its purification process—is the most dramatic stop on the tour. With its whirling mechanisms, gigantic spinning wheels, and twisting, turning contraptions, the room resembles something from Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, but with an end product of clean water. It is an impressive display of functioning technology that is entirely powered by steam.

While the plant may have originally been conceived to combat fire, the Shreveport Water Works Museum now provides a study of the past; a glimpse at the marvels of once advanced, now antiquated technology; and an in-depth look at a commodity most take for granted: clean, accessible water.

“It is,” says Kevin, “a true hidden treasure of Shreveport.”

Vona Weiss is a freelance writer whose work includes magazine articles, essays, and short stories. As a former AP calculus teacher, she spent many years facing a room full of teenagers before opting for something only slightly less terrifying: a blank computer screen and a looming deadline. Vona lives in Shreveport, Louisiana, with her husband, Jeff, where she spends much of her time trying to keep her crayons in order, her desk clean, and the angry villagers at bay.