Foodways

New Orleans Street Vendors

A long history of African American entrepreneurship

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: January 25, 2021

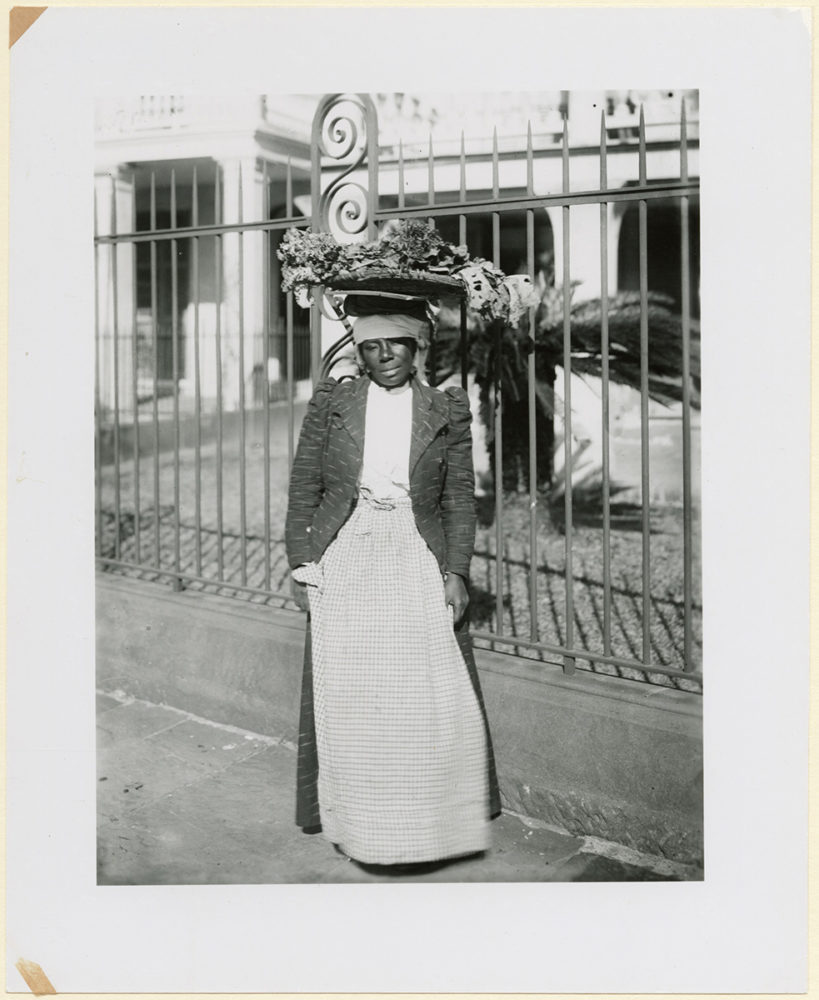

Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston; The Historic New Orleans Collection

Street vendor peddling vegetables.

Before the Civil War, black vendors rented stalls in the French Market or on the levees; these were primarily enslaved women who were allowed to sell products on behalf of their owners. They created a flourishing street-food economy. Lafcadio Hearn, the nineteenth-century author, was fascinated, noting, “There have never been so many fruit-peddlers and viand-peddlers of all sorts as at the present time—an encouraging sign of prosperity and the active circulation of money.” In the previous century, a coffee vendor named Rose Nicaud earned enough selling coffee and calas (fried sweet rice balls) after Mass to purchase her freedom. She went on to expand her business to comprise several stalls in the French Market, and her legendary status inspired many others to pursue similar businesses, particularly after the Civil War, when thousands of formerly enslaved people migrated from neighboring parishes desperate for work.

The post-war period saw the rise of cuisine pour dehors cooks. Before the days of Uber Eats and Waitr, New Orleans was home to a business concept established by newly emancipated black women catering to—and for—white housewives who either could not or would not prepare their own meals. The cuisine pour dehors women prepared full meals, packaging them in individual metal cans that could be transported and delivered on a rack with small amounts of lit charcoal to keep the dinner warm.

By the twentieth century, city regulations and fines began to deter street food vendors. As supermarkets and brick-and-mortar shops became the norm, the cries of the vegetable man diminished. Long gone are the days when the Oyster Man could be heard swinging his tin pails of fresh oysters, singing to the housewife:

Oyster Man! Oyster Man!

Get your oysters from the Oyster Man!

Bring out your pitcher, bring out your can,

Get your fresh oysters from the Oyster Man!

Our contemporary food industry owes a great deal to these ingenious entrepreneurs who commercialized their labor into lucrative businesses to provide for themselves and their families, and the entrepreneurial spirit still lives. For decades, many New Orleanians heard the singsong calls of Arthur J. Robinson, known as “Mr. Okra,” enticing them to come outside for a curated experience of fresh produce. Robinson, a standard-bearer in the street-food vendor culture, passed away in 2018. Now, the twenty-first-century “Oyster Man” can be seen late at night grilling charbroiled oysters outside of nightclubs like the Prime Example Jazz Club at Broad Street and St. Bernard Avenue. This particular New Orleans tradition, rooted in the city’s past and its distinctive food heritage, continues, making way for new takes on centuries-old practices.

Zella Palmer, educator, culinary historian, author, and filmmaker, serves as Chair and Director of the Dillard University Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture. Palmer is committed to preserving the legacy of African American, Native American, and Latino foodways in New Orleans and the South.