White-Bread Evangelist

The starchy Acadiana staple is anything but plain

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

All photos by Lucie Monk Carter

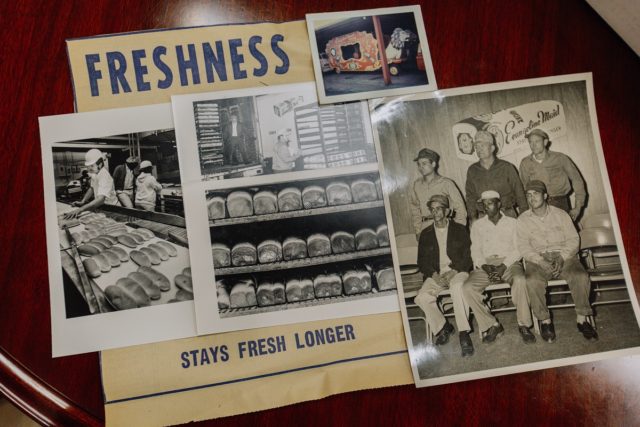

A rotating loaf of bread entices starch-curious passersby.

For decades, Acadians have sopped slices of Evangeline Maid white bread in their gumbo. Throughout the region, fried bone-in pork chops arrive sandwiched between the same. Plate lunches and school lunches, whether made at home or in a cafeteria, always come with a slice or two. Its name long ago achieved grocery-shelf ubiquity: there’s the original Evangeline Maid Thin Sandwich loaf, the slightly larger Giant sack, Evangeline Maid hot dog and hamburger buns, and, of course, Evangeline Maid po-boy loaves. If you’ve spent time in Acadiana, you no doubt know the packaging well: a red, white, and blue plastic sack stippled with yellow fleurs-de-lis—thus combining the four colors of the Acadian flag.

And then there’s the Evangeline Maid logo, the Evangeline Maid herself, wearing what appears to be a mid-twentieth-century cross between a sailor dress and a nurse’s uniform. Is this what Longfellow had in mind? I remember thinking as a confused youngster familiar with the poet’s epic poem. As I grew older, my thoughts turned inward, and only more muddled—Am I the only one who fantasizes about the white-bread lady?

When I was growing up in Lafayette, Evangeline Maid meant forbidden fruit in more ways than one. White bread was banned in my household. My mother insisted on Roman Meal brand bread. French toast, peanut butter and jelly, BLTs, and my daily brownbagged school lunch of turkey and French’s mustard all came served with slices of that insipid brown bread. I realized years later, much too late to develop a taste for white bread, that those loaves—as dense and tasteless as a brick—are sacrilege to sandwich purists. I realize now that my experience among the generations of post-Boomer children was unexceptional. White bread was like iceberg lettuce and mayonnaise, not only unsophisticated—cue the “white bread” pejorative—but downright unhealthy. Everything in moderation, nutritionists tell us, to which the food fearmongers add, Except those things that you shall never, ever eat.

Last year, the company that began baking loaves of Evangeline Maid—as well as its sister loaf, New Orleans’s Bunny Bread—commemorated its centennial. As Acadiana celebrated, instead of commiserating with my fellow non-white-bread eaters, I set out in search of the homegrown loaf I could never call my own.

Joseph Huval was a bread man, born and bred. Raised on an Iberia Parish farm, Huval began working as a New Iberia baker’s apprentice at the age of fourteen. For the next decade, he learned and plied his trade up and down the Gulf Coast, from Lake Charles to Biloxi, mixing, kneading, and baking dough. In the Army, during World War I, he manned field ovens, supplying bread for half of the American Expeditionary Forces. With a fifty-dollar bonus awarded for his military service, Huval started his bakery in 1919, in Youngsville, then a small village just south of Lafayette. He baked what he called Mother’s Bread—named for his mom’s recipe—and vended the loaves door-to-door in a Ford Model T. A few years later, Huval purchased the Lalonde Brothers Bakery, a small outfit in the La Place neighborhood adjacent to downtown Lafayette, and relocated his bustling business there. La Place, a shortened form of La Place des Creoles, for the people of color who originally settled the unincorporated area, was more familiarly known as Fightingville. In the nineteenth century, as local legend tells, back when it was illegal to fight within city limits, men would meet here to engage in fisticuffs and duels. Other, perhaps more peaceful-minded individuals, nicknamed this neighborhood Promised Land.In the early years of the Huval Bakery, the bread business was the promised land. In 1890, women home-baked 90 percent of the bread consumed in America. By 1930, that statistic had flipped: factories, owned and operated by men, produced 90 percent of American bread. Among other social and economic shifts, credit the miracle of sliced bread, first sold by the Chillicothe Baking Company of Missouri in 1928. “The housewife can well experience a thrill of pleasure when she first sees a loaf of this bread with each slice the exact counterpart of its fellows,” a reporter for the Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune wrote upon witnessing the greatest thing since whatever was considered the greatest thing before sliced bread. “So neat and precise are the slices, and so definitely better than anyone could possibly slice by hand with a bread knife that one realizes instantly that here is a refinement that will receive a hearty and permanent welcome.”

Flush with sliced-bread riches, Huval moved his bakery to larger digs, one block east along Simcoe Street, in 1937. Bread trucks delivered the soon rechristened Evangeline Maid loaves—its name a hat-tip to the Evangeline poem—across much of Acadiana. Huval’s daughter Mary Helen modeled for the instantly iconic smiling Maid logo. A decade later, Frem F. Boustany, a Lebanese immigrant who had become a leading Lafayette businessman, purchased a half-share in the Huval Baking Company. Serving as executive vice president and general manager, Boustany introduced resealable wrappers and the memorable “Stays Fresh Longer” slogan. In 1960, the company unveiled the three-dimensional billboard that features a massive rotating loaf of Evangeline Maid, a local landmark, most native Lafayettiens will agree, rivaled only by the Superdome-in-miniature we call the Cajundome.

Boustany bought Huval’s half-share in 1961, and, five years later, brought the Evangeline Maid loaf to New Orleans, sold under the name Bunny Bread (the recipe, a company representative tells me, remains the same). In 1976, the baked-goods conglomerate today known as Flowers Foods gobbled up Boustany’s company, bringing Evangeline and Bunny under their umbrella.

I remember taking a field trip to the old Huval baking facility in the third grade. We were promised, if we behaved, a treat at tour’s end. Safe to say, my classmates and I were angels that day, and we each left with a honey bun to devour on the bus back to school.

I recently recreated that tour under the guidance of Farley Painter, a Flowers Foods general manager at that same factory. I strapped on a pair of hairnets, one for my head and another to cover my scraggly face, and retraced my adolescent footsteps. Painter started here twenty-six years ago, sweeping floors for a spell before working his way up to management. He knows his bread, able to toss out numbers like an auctioneer. The production line uses over nineteen thousand pounds of yeast and one hundred thousand pounds of flour every day to produce six thousand loaves of bread—that’s Evangeline Maid and other Flowers subsidiary brands like Nature’s Own and Wonder Bread—every hour.

Crumbs crunched underfoot as we walked past massive fermenting tanks, Prius-sized proofing bins, Escherian conveyor belts, and a pair of ovens, dating from the early 1950s, that resembled interstellar transport shuttles: boxy but sleek behemoths of gleaming chrome. Painter paused toward the middle of the production line. This is where workers hand-twist two pieces of dough into a single, oven-ready plait, a bit of old-fashioned artisanry that gives Evangeline Maid—as well as Bunny Bread—its distinctive density and roof-of-mouth-sticking tensility. He offers an analogy: think single strand versus braided rope. Weaving provides strength. And though South Louisianans prefer air-pocked, feather-weight French bread for their po-boys, they depend on steroidal slices to hold scoops of peanut butter or breaded and fried pork chops. That twist defines our “regional profile,” Painter told me, “our taste repertoire.”

So much work goes in to create this humble loaf. Perhaps Daniel Defoe said it best in Robinson Crusoe, wherein the shipwrecked sailor learns to survive on bread he crafts from seed to loaf. “It is a little wonderful,” the explorer remarks, “the strange multitude of little things necessary in the providing, producing, curing, dressing, making, and finishing this one article of bread.”

I exited the factory, my pores seeping yeasty scents, an oven-fresh Evangeline in hand, just like the bakery’s employees, who earn a free loaf at the end of each shift (production of the honey buns and other sweets were relocated to another Flowers factory long ago). Outside I met Dirk Guidry, who had recently completed a month-long mural commission on the bakery’s south facade. A pair of dough-kneading hands is flanked by the original Huval bakery and a midcentury-era delivery truck. A picnicking family, some modeled after members of the Huval family, including a young girl named Evangeline, share a table. Joseph Huval looms over a cypress bayou sunrise, slicing bread from an enormous loaf. Three slices drift on the water, holding afloat the three iterations of the Evangeline Maid logo—over time, her skirt growing shorter as her heels rise taller. A white-sacked loaf rises above, like a halo. In a city of outstanding murals, artistic aide-mémoire of the city’s Cajun and Creole culture and heritage, Guidry’s collage of images stands out.

“I was what my grandma called délicat,” Guidry told me, pronouncing the word in Cajun French. “I was very picky. I used to fix peanut butter on Evangeline Maid bread. Ate that every day until seventh grade. I couldn’t imagine how many loaves of bread we went through.” Painter stepped outside to hand Guidry a loaf, soon to become some Evangeline bread pudding for his wife, who had delivered their second child just a week before.

But would there be any hope for me, a sliced-white holdout?

I called my friend and neighbor Larry Miller, co-owner, with his wife, Chef Nina Compton, of two of my favorite New Orleans restaurants: Compère Lapin and Bywater American Bistro. During Creole tomato season, Larry eats a tomato sandwich on Bunny Bread nearly every day. He is Instagram famous for, among other things, making tomato sandwiches for his friends. If anyone could turn me into a white-bread appreciator, it is Larry.

I met Larry in the Compère Lapin’s post-lunch-rush kitchen with my gratis loaf of Evangeline Maid and a half-dozen off-season Kentwood tomatoes. He fetched two slices from the bag, a plastic tub of aioli, and got to sandwiching. “I like a healthy amount of mayonnaise,” he said while schmearing both halves, “Blue Plate, usually. Growing up, my born-again parents wouldn’t let us have Hellmann’s because of the name.” Next came two thick tomato slices, a great sprinkling of flaky salt, and several twists of fresh ground pepper. He folded the bread halves together before plating the sandwich with all the gusto of a Michelin-starred chef.

I ate half that sandwich, more white bread than I’d ever eaten in all my life. I’m sorry to say I might have disappointed Larry for not devouring the entirety of his handiwork. But, as I headed home, those slices of Evangeline Maid stuck with me (and, true to form, stuck all up in my gums and teeth). It was true: there was a sandwich-y je ne sais quoi that only white bread could offer. I would wait until better tomatoes could be acquired. I might, bread gods forgive me, resort to toasting. I looked forward to next summer.