Latest

Tales from Wartime New Orleans

WWII–era parallels to the current COVID-19 crisis, presented in partnership with the National WWII Museum

Published: April 22, 2020

Last Updated: September 5, 2022

Photograph by John Vachon, Library of Congress

Line at the Rationing Board on Gravier Street in New Orleans, 1943.

April 22, 2020

When will this current crisis end? When will life return to normal, and what will normal look like when the crisis is over? In the present, very uncertain moment, it’s natural and can be comforting to look back on other life-altering moments in American history. World War II has emerged as a leading cultural reference point during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global shortages, fear, and uncertainty all have parallels in the World War II era. Then as now, the geography and character of New Orleans has flavored the local response.On March 6, 1942, New Orleanians gathered for what would now likely be termed “Blackout Fest.” That night New Orleans experimented with its first blackout drill. Considered a possible enemy target because of the importance of the port, New Orleans was ordered to practice this wartime precaution undertaken in other coastal cities. At 9 p.m. blackout sirens throughout the city rang out, and homes and businesses darkened lights. During this first 22-minute drill, Canal Street, the city’s main artery, was packed with festive, curious citizens waiting to see New Orleans’s busiest area in total darkness. New Orleans passed the drill, and local civil defense organizers, who cited 99 percent compliance, deemed the exercise a success.

The blackout drill was just one way the war manifested itself in the city and state. The National WWII Museum’s Pelican State Goes to War: Louisiana in World War II exhibit explores the many contributions made by the state and its citizens to the war effort. Louisiana’s maritime industry generated some of the most integral and recognizable craft of the war with Higgins Industries, central to the founding of The National WWII Museum, designing and producing over 20,000 landing craft for the US Navy. Prior to the war, Higgins’s output centered primarily on workboats for fur trappers and the oil and gas industries. Just as distilleries are expanding business models today—brewing up high-proof hand sanitizer alongside their usual potable products (according to one young family friend, Celebration Distillery’s “smells like margaritas”), many Louisiana businesses like Higgins expanded production or shifted focus to meet wartime demands. Crescent Bed Company, for instance, known for making iron beds and cribs, transitioned to fabricating berths for the Liberty ships taking shape at Delta Shipbuilding Company. In the current crisis, businesses are again stepping up to fill a need, this time for personal protective equipment (PPE). GoodWood NOLA furniture company, Nunez SkillShop, NOLA Couture, and other collaboratives are fabricating face shields and masks for supply to local hospitals. One driver of these efforts and chief beneficiary of these critical supplies, the Ochsner Health System, has roots in World War II. Ochsner Clinic was founded in 1942, and the flagship Jefferson Highway campus evolved out of the purchase of the old Army Station Hospital at Camp Plauché in 1947.

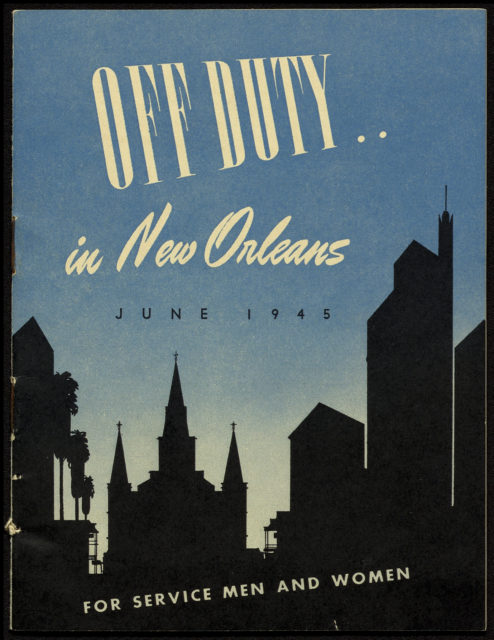

Though Louisiana during WWII was home to less than 2 percent of the nation’s population, it is estimated that one-third of the 16 million Americans who served traveled through Louisiana or New Orleans during the war through training or deployment. Production jobs in New Orleans also brought large numbers of workers to the city from rural, more-impoverished areas of the Gulf South. The city was brimming with soldiers looking for fun and workers looking to blow off steam and spend money.

Shortages, hoarding, and price gouging led to implementation of rationing across the nation. Instead of Rouse’s and other grocery stores limiting shoppers to one pack of toilet paper or hand sanitizer, it was Uncle Sam and sugar. Louisiana’s cooks joined others in learning to navigate new wartime kitchen regimens. Sugar was the first and longest rationed good, from 1942 to 1947, and was the most commonly missed, but the scarcity of coffee was particularly troubling for Louisiana’s java junkies. One pound of coffee for five weeks, even if stretched with chicory, was unthinkable. Luckily, coffee rationing only lasted for around 10 months. To manage the effects of rationing, some things got smaller (two-cup “honeymoon size” coffee pots; think “pods”) and some things got bigger (thrifty quart-size beers, perfect for “splitting when you’re out with friends;” think “growlers”). Wasting food was unpatriotic, like “throwing victory in the garbage can,” proclaimed one government film short. Americans were encouraged to grow food in victory gardens, can food, substitute, and conserve. (“Do with less, so that he’ll have more.”)

A certain consumer, the federal government, was at the front of the line, martialing . resources to feed those in service. One Louisiana company that thrived due to Army quartermaster business was Trappey’s Foods in Lafayette. Trappey’s had adapted a method to use less-than-perfect sweet potatoes in their canned candied yams. By the end of the war, they had supplied 12 million pounds of canned sweet potatoes to the military.

Like today during the current COVID-19 pandemic, Louisiana’s food and restaurant industry was under strain, though not from closures or a lack of business, but rather from an excess of business and dearth of supply. Eating out was an appealing option for workers with wartime paychecks and less time to spend in the kitchen. War-industry workers and tourists wanted to sample the state’s famous local cuisine, and restaurants were in high demand. One report from the Louisiana Restaurant Association cited the serving of 267,000 meals (a number equal to roughly half the city’s population) in one single day in New Orleans in 1945. For restaurant-goers, another appealing aspect of eating out was that the burden of rationing fell not on the individual consumer, but on the establishment. Restaurants received ration allotments based on the number of meals served in one survey week in December 1942. In order to stretch supplies, restaurants served certain items only at particular meals (during breakfast and dinner service, for example, rather than lunch); sugar bowls disappeared from tables.

In order to cut back on service, restaurants practiced Meatless Mondays and Tuesdays. They served alternative cuts of meat and less common meats in general, like alligator, rabbit, or even muskrat. (Per a 1944 Louisiana law, muskrat could be labeled and sold as “marsh hare,” with the Louisiana Conservationist suggesting several ways to serve the “versatile marsh hare,” including breaded and fried, and proclaiming, “These golden brown breaded pieces of meat will keep your guests guessing.”) Catfish got a makeover as “Tenderloin Trout.” Fresh seafood, although not rationed, was sometimes unavailable due to labor shortages and the cannery demands, as canned seafood was a priority item for the military. A few restaurants in New Orleans were forced to close, unable to stand up under wartime demands and restrictions. Others found creative ways to get by. Hubig’s Pies survived thanks to its owners and employees, who donated their personal sugar rations to the bakery.

In a widely distributed article in August 1943, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist S. Burton Heath described New Orleans as a “war tourist mecca.” His headline read, “New Orleans Takes War Boom in Her Stride, Remains Her Own Charming, Leisurely Self.” He wrote that we, the “New Orleans-eans,” believe that the “object of living is to live well.” Lady New Orleans is cast as alluring, but unknowing throughout: “Romantic old New Orleans has achieved something that approaches the impossible. By some hocus-pocus she has managed to bulge at the seams without appreciably losing her well-known sex appeal…the Crescent City is like a cafe society dilettante who has taken a 53-hour-a-week job in a shipyard and still keeps looking as though the heaviest thing on her mind was the danger of chipping her fingernail polish.” Was it that “she didn’t know enough about what was ahead to get hysterical,” as Heath suggested or was the curious, resourceful city winking behind his back?

Today New Orleans remains curious and resourceful with citizen-led projects sustaining musicians and hospitality workers, face mask and gown production taking place in homes around the city, and victory gardens sprouting up again as access to fresh food has become more difficult. Unlike in World War II, these phenomena are largely localized and community-generated, rather than federally directed. The rallying cry of “We’re all in this together” has been pulled out of the slogan arsenal and deployed by companies, agencies, and officials. It remains to be seen whether the response to COVID-19 in New Orleans will be cited, alongside World War II, as an example of American strength and resiliency. Victory is still uncertain.

There are numerous wonderful sources for wartime Louisiana history, including: Louisiana during World War II: Politics and Society, 1939–1945 by Jerry Sanson, War Stories: Remembering World War II by Elizabeth Mullener, New Orleans Goes to War, 1941–1945: An Oral History of New Orleanians during World War II by Brian Altobello, New Orleans in the Forties by Mary Lou Widmer, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II by Jerry Strahan, Making New Orleans by Philip Collier, as well as Bourbon Street: A History by 64 Parishes columnist Richard Campanella.

There are numerous wonderful sources for wartime Louisiana history, including: Louisiana during World War II: Politics and Society, 1939–1945 by Jerry Sanson, War Stories: Remembering World War II by Elizabeth Mullener, New Orleans Goes to War, 1941–1945: An Oral History of New Orleanians during World War II by Brian Altobello, New Orleans in the Forties by Mary Lou Widmer, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II by Jerry Strahan, Making New Orleans by Philip Collier, as well as Bourbon Street: A History by 64 Parishes columnist Richard Campanella.

This article is brought to you in partnership with The National World War II Museum. The museum remains temporarily closed, but our work continues online, exploring the story of the American experience in World War II and what it means today even during this most challenging time. The museum continues to collect stories of experiences during World War II, although in-person interviews are currently on hold. For more information about contributing to our archives contact [email protected].

Kim Guise is the Assistant Director for Curatorial Services at The National WWII Museum, where she has worked with the collection since 2008, specializing in wartime correspondence, the American home front, and US prisoners of war. A Gretna, Louisiana-native, Guise holds a BA in German and Judaic Studies from UMass Amherst and a MLIS from LSU.