Great American Steamboat Race

A river race aimed to raise spirits in the war-battered South

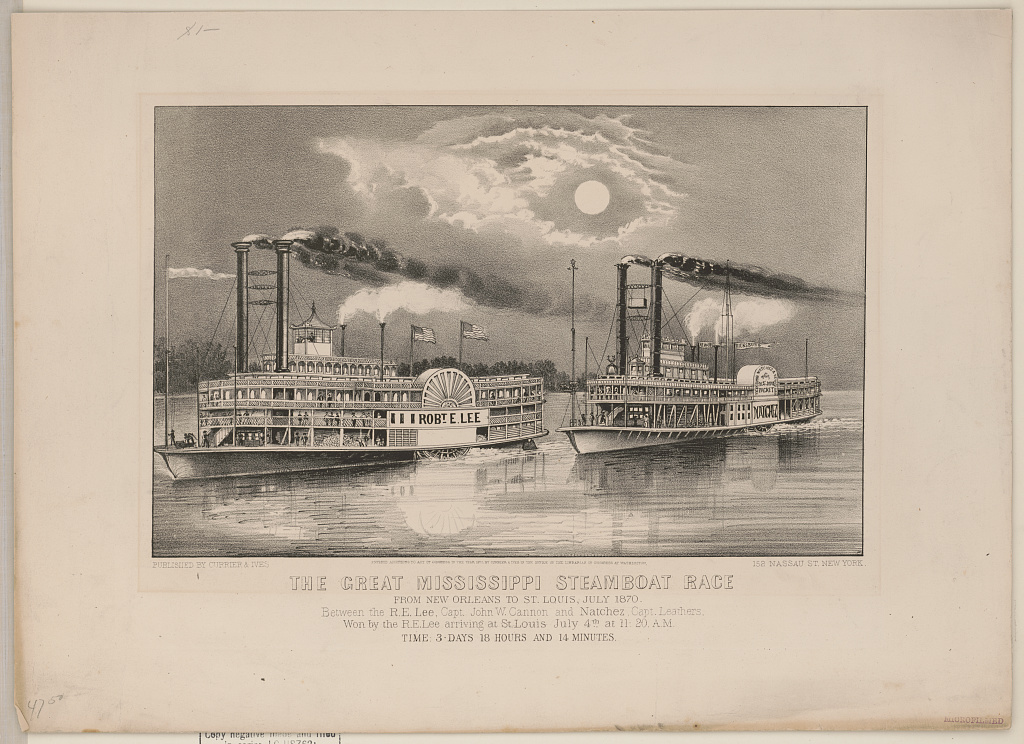

Currier & Ives, Library of Congress

The great Mississippi steamboat race: from New Orleans to St. Louis, July 1870

An event that became known as the Great American Steamboat Race pitted the steamboats Robert E. Lee and Natchez in an epic twelve-hundred-mile race from New Orleans to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1870. In the years following the Civil War, the American South saw little in the way of uplifting public festivities. The stage was thus set for an incident that appealed to the sporting heritage of thousands throughout the Mississippi Valley. Although steamboats had been racing for years, none stoked the national imagination as did this one. The personalities of the well-known captains and the mystique of their state-of-the-art boats were media magnets. Too, everyone knew that the glory days of steamboating had passed, as the growing web of railroads strangled the river-bound industry, and that this might be the last great steamboat race.

The Captains and Their Boats

Gruff, profane, and physically imposing, fifty-four-year-old Thomas P. Leathers grew up in the steamboat business, building his own boat at age twenty-four, and labored his way to the top. By the time of the Civil War, Leathers had owned five consecutive steamers, each named Natchez, and each larger and faster than its predecessor. In 1861, the fifth Natchez carried Jefferson Davis to Montgomery, Alabama, where he was sworn in as president of the Confederacy. Leathers lived in New Orleans and aggressively nurtured his own brash reputation up and down the Mississippi River.

The sixth Natchez was launched at the Cincinnati boatyard in 1869. She was 303 feet long and forty-six feet wide. Twin paddlewheels were forty-two feet in diameter and eleven feet wide. Her eight boilers were thirty-three feet long and generated 160 pounds of pressure. Thirty-six–inch-diameter cylinders had a ten-foot stroke. Designed specifically to be faster than the Robert E. Lee, the Natchez began breaking speed records on the river soon after launch.

Other than an abundance of experience in the steamboat industry, fifty-year-old John W. Cannon had little in common with Leathers. A quiet, astute businessman, he had owned at least a dozen steamers and managed to make a small fortune hauling freight during the war. His wartime profits were used to build the Robert E. Lee. By then, he had learned first-hand the dangers of his occupation when the boilers on his boat, Louisiana, exploded at the New Orleans wharf, killing eighty-six people in 1849.

Designed to be the fastest and most luxurious steamer on interior rivers at the time, the Robert E. Lee was launched on the Ohio River from New Albany, Indiana, in 1866. She was 285 feet long and forty-six feet wide. Her paddlewheels were thirty-eight feet in diameter and seventeen feet wide. Eight boilers were twenty-eight-feet long and generated 110 pounds of pressure. Her slightly larger cylinders, forty inches in diameter, may have influenced the race.

The Race

Leathers and Cannon were well-acquainted business rivals and personal adversaries. Leathers often challenged Cannon to race. Once, in a New Orleans tavern, the hostility turned into a fistfight in which an onlooker said Cannon got the upper hand. As Leathers’s challenges mounted, newspapers and Cannon’s customers up and down the river encouraged him to race. Reluctantly, he relented, preparing for the race in a methodical, businesslike manner. He stripped the Robert E. Lee of all unnecessary weight and made arrangements for mid-stream fuel deliveries all the way to St. Louis. No freight was carried and the passenger list was restricted. In contrast, Leathers, exuding confidence, stated that he would carry a routine load of passengers.

The race was scheduled to begin on the afternoon of June 30, 1870, resulting in an immediate press frenzy across the nation that only grew as the race played out, as well as an unprecedented amount of betting on the winning vessel. The New Orleans Picayune reported, “The whole town is given up to the excitement occasioned by the great race. . . . Enormous sums of money have been staked here on the result, not only in sporting circles but among those who rarely make a wager.” In New Orleans and every village and city along the route, observers noted record crowds when the boats passed.

The starting line where official times began was St. Mary’s Market near Canal Street. At two minutes before five o’clock, the Robert E. Lee charged past the line with a full head of steam and fired her cannon. Four minutes later the Natchez’s gun boomed in reply, and the race was on.

Elite crews of laborers, firemen, and engineers bent to their tasks of feeding and nursing the giant engines, aiming to yield their maximum drive without exceeding pressures that would result in a disastrous boiler explosion. Likewise, experienced pilots guided the vessels through a gauntlet of sandbars, snags, and shifting currents.

Shortly into the race, potential crises aboard the Robert E. Lee were averted when engine water leaks were repaired with little loss of time. She passed Baton Rouge and a large cheering crowd at 3:00 a.m. with the Natchez in hot pursuit. At the mouth of the Red River the next morning, the times of the two boats were identical. Leathers had set the record for the run from New Orleans to Natchez, Mississippi, fourteen years earlier on another steamer, but on July 1, the record fell to Cannon by nineteen minutes. At Vicksburg the Robert E. Lee maintained the lead, but only by eight minutes. By late that night, when the boats passed a fireworks display in Memphis, Tennessee, Cannon’s lead had surged to almost an hour as Leathers was plagued with mechanical problems and groundings. Continuing, the Robert E. Lee broke another longstanding record by reaching Cairo after three days and one hour. Natchez was twenty miles behind at this point.

As the steamboats entered the most treacherous part of the river between Cairo, Illinois, and St. Louis, fog set in and sealed the fate of the Natchez. Cannon, with local pilots, was able to ease his way through the fog and darkness at idle speed. Leathers, after repeated groundings, was forced to tie up for several hours to wait out the fog. As a result, the Robert E. Lee dashed into St. Louis and was greeted by a cheering crowd, screaming boat whistles, and an artillery salute. The official time from New Orleans to St. Louis was three days, eighteen hours, and fourteen minutes. Not only had the Robert E. Lee beat the Natchez soundly in a heads-up race, she set a new record for the run—a record that had been established by Leathers and the Natchez only two weeks earlier.