Magazine

The Rebel in Us All

School desegregation in Caddo Parish, Louisiana

Published: February 28, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photo by Jeremy Hernandez

Sonja Dennis (left) and Brenda Grundy Wells in front of North Caddo High School.

The Caddo Parish seat is Shreveport, located in Louisiana’s northwest corner and home to the courthouse where the last Confederate flag was lowered signifying the South’s surrender after the Civil War. The Sagas story, focusing on two racially segregated high schools that opened after the US Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision deemed the separate-but-equal principle unconstitutional, transitions from a walk down memory lane into a front-row seat to historic change when a remnant of Caddo’s complicated past—the North Caddo High “Mr. Rebel” mascot—is replaced.

In 1955 North Caddo High opened to serve the white students who lived in the rural part of the parish near Vivian, Louisiana. They waved the Confederate flag and sang “Dixie” at school events. In the adjacent town of Belcher, Herndon High—a comprehensive school for Black students in first through twelfth grade—opened a year later, named for Joseph Herndon, a Black philanthropist who had donated money to Caddo Parish to improve “Negro education.” Ironically, Herndon was a Rebel by association who had fought alongside Confederate troops—not to preserve slavery, but to protect the land he would inherit from his white father.

If Joseph Herndon was rebel-adjacent by fighting for his family land in the Civil War and daring to designate money to improve Black schools, then the people who made up Herndon High were rebels in spirit. The faculty chose Historically Black University–inspired symbols, such as their Rattlers mascot (in tribute to Florida A&M University) and their school colors (black and gold, like nearby Grambling State) to inspire students to set their sights on higher education. And students received the message. For example, Ollie Tyler, the 1963 Herndon High valedictorian and a National Merit Scholar, was the first woman and first African American Superintendent of Caddo Parish Schools. In 2014, Tyler was also the first Black woman to be elected mayor of Shreveport. The separate-but-unequal system can produce success stories—fortuitous since these segregated schools were still in operation sixteen years after Brown.

Reverend Abraham, part of the Herndon senior class of 1965, remembers his days as a Rattler: “We heard about white schools. Herndon was all Black and they were all white. And that was basically it. We didn’t feel like they were any better than us. We didn’t have all the subjects probably that we should have had, but we had your basics: your reading, writing, and arithmetic, and we excelled at that.

“We knew that we were going into a world that was full of discrimination because of your color. And so we were taught that you had to work harder, you had to be twice as smart. And that was our goal.

“When we would start school at the beginning of the year, we would get books from North Caddo. It was the white school in Vivian. That’s how we looked at it. We thought they were new books. And we would open a book and there was a kid’s name in it. But it was fine with us. When we let a book go, it was gonna be well used.”

Dr. Helen Kennedy Wise, a sociology professor at Louisiana State University Shreveport, attended North Caddo High in the 1980s. She explained: “My parents went to North Caddo. My father lived in Vivian. My mother lived in Oil City. They ended up at the same high school. I remember looking in her yearbook. There weren’t any Black people there. Their senior yearbook is a Rebel flag. I mean if you open it up and lay it flat, it is a Rebel flag. It was very normal.

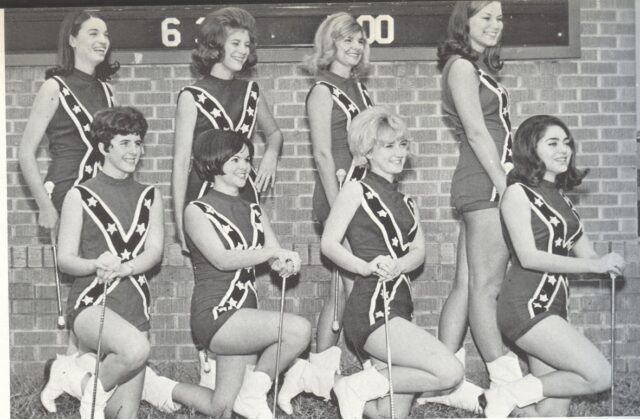

North Caddo High’s majorettes wear Confederate battle flag leotards in this 1968 yearbook image. Bishop Blue Foundation.

“I had a T-shirt when I was seven years old that my dad bought for me. It was a baseball shirt, and it said ‘The South Will Rise Again.’ I grew up and watched The Dukes of Hazzard and thought that I want to marry Bo or Luke Duke. We watched Gone with the Wind on loop at our home growing up. I mean that was sort of this idyllic thing.”

Over at Herndon High, even when desegregation was mandated on the national stage, the idyllic situation for Reverend Abraham was to remain at the school he loved. He had no interest in leaving: “Matter of fact, the rumor was out my senior year at school that we may have to integrate and we did not want to go to North Caddo. There would’ve been a lot of problems with us going because we were probably a little different than the ones that did integrate. I think we were more militant. We were very proud of our own family. Herndon was a family school, and we were very proud of that.”

Desegregation came to Caddo Parish in stages. The “rumor” Abraham referred to was the 1965 Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board lawsuit, which resulted in a court order for Caddo to desegregate schools by August. The school board responded with a “freedom of choice” plan, allowing Black students to apply to attend formerly all-white schools on an individual basis.

Herndon High student Brenda Grundy Wells applied to attend North Caddo after questioning systemic inequity: “I was one of the students that got to hand out supplies. We got two yellow number two pencils and brown paper, not white writing paper. Well, I knew other kids—white kids—got white paper. Caddo Parish would send [us] about three or four boxes of books, and the books were used. They had three or four pages torn out of sections of the book. If you’re missing a section of the book, you couldn’t get your lesson.”

Wells’s transition to North Caddo had its difficulties: “Ongoing all the time at North Caddo . . . you were treated differently, badly. But my grandmother said your purpose is to learn, your purpose is to get a diploma. Your purpose is not to fight or act up. And you wanted to do some of those things, but my grandmother put the fear of God in you.” In 1969, Wells became the first Black graduate of North Caddo High.

A few brave students transferred from Herndon to North Caddo under freedom of choice. But when Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education reached the Supreme Court in 1969, Justice Thurgood Marshall recommended immediate, large-scale desegregation beginning with the 1970 spring semester. The court agreed. If Brown was an order, Holmes was an ultimatum. So the Caddo school board sent Herndon Rattlers to the much smaller North Caddo campus to become Rebels.

Jules Fogel, editor of Vivian’s Caddo Citizen, anticipated the court-ordered change hurting white and Black community members alike in his Town Talk column in 1969: “The tragedy of what is happening is that both races will suffer. . . . The white student will be held back from achieving the utmost in his education during his formative years, and the Negro will be placed in a situation that will put him in an unenviable position of ‘not belonging.’ We must remember that the rural Negro adult has two major interests . . . his church and his school. One is being taken away from him.”

Charles Bradford was a sophomore at Herndon in 1970: “Oh man, those times at Herndon were great. I started first grade, went all the way up to my sophomore year. We know what a Rattler is. And that was our mascot. To be feared. I mean no one would mess with the Rattler.”

He dreaded the move to North Caddo High: “Their mascot was a Rebel. Okay. Seriously, it didn’t feel good at all. I mean we understood what that word ‘rebel’ meant. We didn’t like it, to be honest with you, but of course we didn’t have a choice. So we had to deal with it. We were only fifteen, sixteen years old at the time. And there were some things we did not understand; some things we did. There was still, for lack of a better word, hatred between Blacks and whites. And that sort of fueled the fire, more or less, when we went to North Caddo.

We knew that we were going into a world that was full of discrimination because of your color. And so we were taught that you had to work harder, you had to be twice as smart. And that was our goal.”

“We had a problem with it because North Caddo was small. It was much smaller than Herndon. They had to bring in fabricated buildings to accommodate us.

“You had all these white individuals staring at us like we don’t belong. And thank the good Lord because some of our teachers from Herndon came with us . . . to more or less keep some of us in line because we were upset.”

The tensions settled, but the experience was bittersweet for Bradford: “We still consider Herndon High School our school. We graduated from North Caddo. But we still look at Herndon to this day as our school. North Caddo was a drive-by. Now going forward, I can’t speak for the class beyond that. But for us it was just a stop-over.

“It was an experience. Now, how great of an experience? Was it a positive experience? It did teach us things. You know, nothing’s perfect, first and foremost. There are always going to be obstacles. It just all depends on how you arise to those obstacles.”

North Caddo High and Herndon students continued to rise to the challenges created by change over the decades. By the 1980s, Herndon was rebranded as a magnet middle school. Dr. Wise was part of the first class in the desegregated school and helped replace the Rattler mascot: “At a new school, the first thing they would say is ‘What’s our mascot going to be?’ And that was a reflection of the student body at the time. All around Herndon is literally a cotton field, and I can remember somebody saying, ‘We should be the cotton pickers.’ That was an actual name.

“We became the Herndon Hawks because there’s a lot of roadkill on Highway 71. But never was there a reference to it having been an all-Black school. I was there in eighth grade when we took Louisiana history. We didn’t learn anything about the history of school integration. We didn’t learn anything about the histories of the school.”

After graduating from Herndon Magnet, Dr. Wise joined the North Caddo High class of 1989 and has complex feelings about the mascot: “To be thought of as a Rebel was more to be thought of as poor white trash than it was to be thought of as a member of the Confederacy. This was the poor school, the school out in the country. To some level, these were hicks. So when you thought of a Rebel, it was more in the vein of Lynyrd Skynyrd and less in the vein of slavery. So for me, that’s how I thought of it.

“And then you still have your people who do not understand that the Civil War was decided years ago. They still walk among us.”

The mascot of North Caddo High remained the Rebel until the summer of 2020. In response to community complaints and the superintendent’s recommendation, Caddo’s school board voted to allow current North Caddo High students to select a new mascot.

North Caddo class of 2021 senior Kaylee Young welcomed the change but questioned its symbolic depth: “My mom’s white and my dad is Black. I felt like the Rebel mascot was a symbol of racism. We voted, and then we became the Titans. I don’t know if I’m stretching it or not, but I feel like it was just another way to pick a white man as our mascot.”

As Reverend Abraham reflected, “The world has changed so much. Because of integration and equal opportunity, kids don’t feel that they have to be any better than anybody else, that they should be afforded the same rights. But we were not afforded that. We felt that we had to be better, and we tried our best to be better. If you had the chance to go to Herndon or one of the segregated schools, they were great schools because they were full of great people. That’s it.”

Currently, Herndon Magnet consistently ranks in the ninety-fifth percentile for high performance among Louisiana’s public elementary and middle schools, and it has a student body that is 80 percent white and 15 percent Black. North Caddo is among the top four highest-performing high schools in Caddo Parish, but it places in the sixtieth percentile of schools across the state. The student population at North Caddo is just over 50 percent white and 40 percent Black.

School Sagas interviewees represent a cross section of ethnicities and ages, with senior citizens remembering parental directives to observe Jim Crow segregation laws, while current high school students recognize that “Colored Only” signs have disappeared but the invisible divisions created by public policy remain and perpetuate inequality. The power of their insights has taken School Sagas from a standalone documentary to a series the researchers are preparing for Red River Radio in 2021.

Liliana Hartfield, a director with the Bishop Blue Foundation, is lead researcher for School Sagas. Other project scholars include North Caddo High graduates Dianna Phelps, now a counselor and sociologist with Philadelphia public schools, and, from LSU Shreveport: sociologist Dr. Helen Kennedy Wise and Dr. Elisabeth Liebert, MLA Program Director; from Southern University Shreveport: Dr. Lonnie McCray, Dean of Humanities, historian and journalist Marquel Sennet, and research assistants Steven Harkness and Julie Stackhaus.

The School Sagas program is funded under a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, the state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities; an African American Civil Rights grant from the Historic Preservation Fund administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior; and the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation. The views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed do not necessarily represent those of the funding organizations.