Summer 2021

The Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience

Opening this year on Howard Avenue in New Orleans

Published: May 28, 2021

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

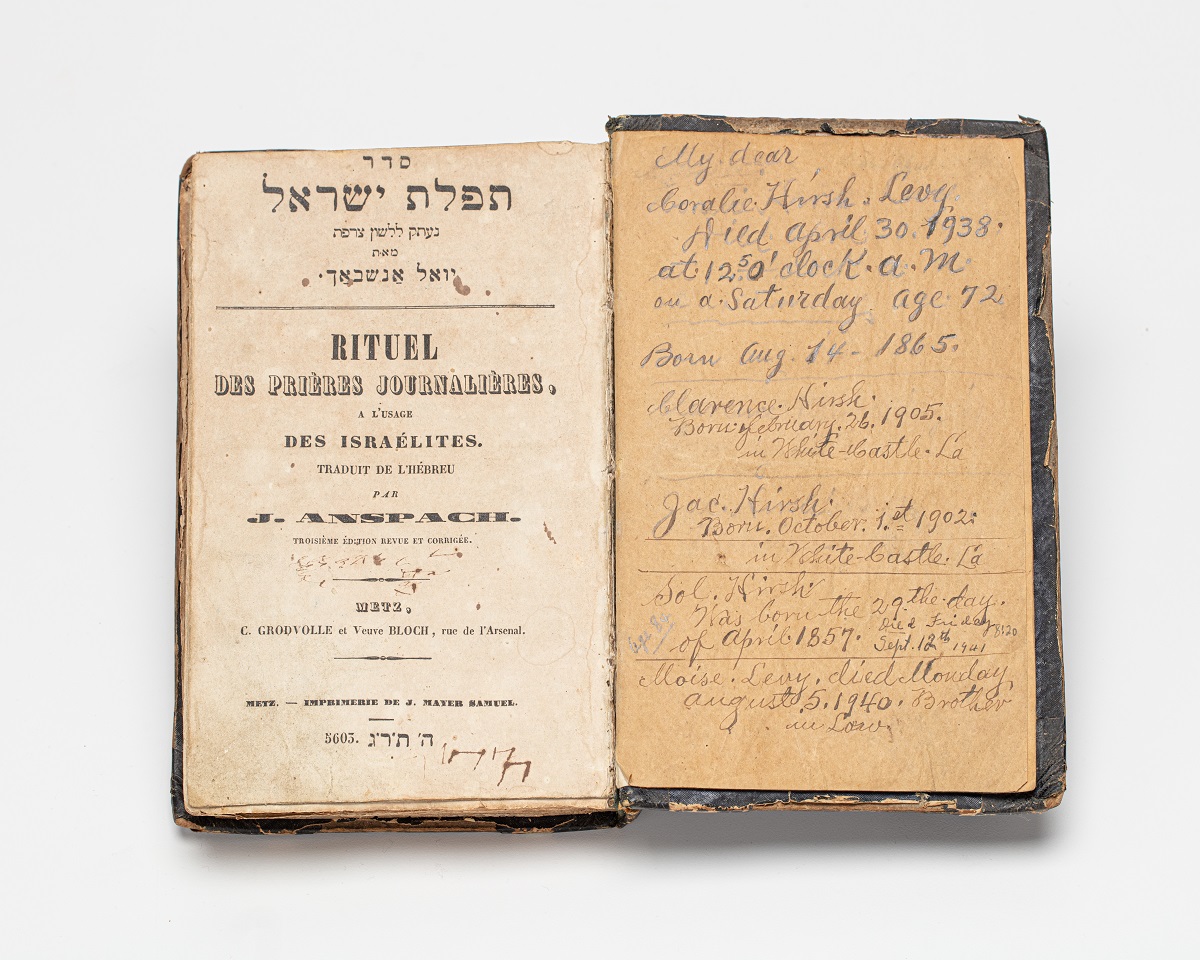

Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, Gift of John Green III

Prayer book in French and Hebrew with family records in English, ca. 1843, from the Hirsh-Levy family of Donaldsonville.

It’s this long history that a new museum in New Orleans seeks to convey. The Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, which opened May 27 on Howard Avenue, will host an array of artifacts, oral histories, and interactive exhibits detailing the arc of Jewish life in the region. That narrative encompasses both bright and dark chapters: Jews finding relative stability in their new homes or, at times, finding their synagogues bombed or their neighbors lynched; Jews involving themselves in the civil rights movement, or, earlier, fighting for the Confederacy. Kenneth Hoffman, the executive director of the MSJE, told me, “There wasn’t just one experience, but there were many. It’s nuanced. We’ll talk about that.”

The Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience’s first iteration opened in 1986 at Henry S. Jacobs Camp, a summer camp for Jewish children in Utica, Mississippi. The previous decades had seen a mass migration of young Jews from the South’s small towns to its urban centers, ultimately requiring a spate of rural synagogues to close their doors for lack of sustaining members. All the sacred objects from those congregations needed a place to go, and the museum at Jacobs Camp served as a sort of clearinghouse for them, preserving prayer books and candlesticks of a fading generation in order to teach the next its legacy. The museum closed its doors in 2012 in part because it was difficult for the general public to access. Now, the MSJE is reopening in an expanded form: not just as a repository of artifacts and photographs but as an educational facility and tourist destination for southern Jews and all others interested in their—in our—history.

My family’s story mirrors one the MSJE will tell. My paternal great-grandfather helped found the first and only synagogue in Martinsville, Virginia, in 1927, where, many years later, my dad had his bar mitzvah. My father grew up working in his parents’ clothing store downtown, one of many Jewish-owned businesses along Martinsville’s main thoroughfare. In the ’80s, he moved to Atlanta and met my mother, whose story resonated with his own. Her parents, Holocaust survivors from Poland, immigrated to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1949. Her father was a carpenter and peddled wares before he opened his own furniture store on King Street. My parents, often one of few Jewish students in their classes growing up, enrolled my brother and me in Jewish schools and summer camps and youth groups. He and I have both ended up in New Orleans, where we meet up for Shabbat dinners and high holiday services and to light Hanukkah candles on Bayou St. John. In a true turn of Jewish geography, the neighbors on the other side of my shotgun double here all met as counselors working at Jacobs Camp, where the MSJE began.

Last January, before COVID-19 drove Jewish gatherings online and pushed back the opening date of the MSJE—the museum was originally supposed to open its doors in 2020—I met with Anna Tucker, the curator of the museum. Inside the library at Temple Sinai on St. Charles Avenue, she laid out artifacts from the museum’s collection: tzedakah boxes and Jewish fraternity memorabilia, immigrants’ diaries and a thick stack of postcards showing the colorful facades of Jewish-owned stores from across the South.

There was something both mundane and moving about that arrangement of objects. I could imagine an Alpha Epsilon Pi composite boasting my uncles’ smiling portraits, or a store ledger’s inventory lists written in the looping cursive my grandmother used to write me birthday cards. I could picture the photo I keep by my desk included in the assortment: a crumpled black-and-white still of my mom’s parents posing, bewildered, in front of the Confederate monument on the Battery in Charleston, my mother and her siblings climbing its pedestal in the background. Every time I look at it I’m struck by the layers of contradiction in the image: the stark symbol of white supremacy as backdrop to my ancestors who’d just crossed an ocean after nearly falling victim to a racist regime. I take some comfort in knowing that there will be a museum dedicated to my people’s complicated slice of the American experience, somewhere I can point to in attempting to explain our place here. COVID-19 will necessitate a quiet start, but I know I’ll be eager to visit when the time comes.

Carly Berlin is the Gulf Coast correspondent for Southerly magazine. She lives in New Orleans.