The Liberace of Wellness

Fans are still wild about French Quarter native Richard Simmons

Published: August 31, 2021

Last Updated: December 1, 2021

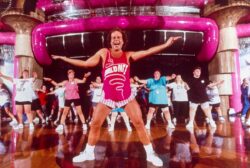

Photo by Evan Hurd, Alamy Images

Simmons exercises with travelers on his Cruise to Lose though the Caribbean, January 14, 1996.

Simmons sweated his way to fame first with live classes at his Slimmons aerobics studio in Beverly Hills, which he opened in 1974. According to a 2013 New York Times profile, he was still, at that point, teaching at the studio in person, as well as through VHS and DVD workout tapes, and he was seriously taking on the internet for the first time, which was the subject of that piece in the paper of record. With a brand-new Facebook page, Google Plus account (which was still a thing in 2013), the YouTube channel, and promotions through heavily trafficked websites like BuzzFeed, Richard Simmons was more visible than he’d ever been—until suddenly, he wasn’t. The Times profile trumpeting his forthcoming online blitz ran in August 2013. Six months later, according to the 2017 podcast Missing Richard Simmons, he failed to show up to teach a class at Slimmons, and hasn’t appeared in public since.

The podcast was the work of investigative journalist and former Daily Show producer Dan Taberski, who was also an acquaintance of Simmons and attended his workout classes. Over the course of six episodes, Taberski doggedly pursued the friends, neighbors, and family of the fitness icon, knocking on doors from Los Angeles to Louisiana. The podcast was a hit—it was mysterious why someone whose brand had always been extreme accessibility had retreated so completely—but the host’s intensity also troubled some listeners. In the New York Times, critic Amanda Hess wrote that Taberski “relentlessly pesters Mr. Simmons and friends for personal details . . . call it a public hounding.”

Still, Taberski wasn’t the only worried fan. In a piece about the podcast’s launch, Times-Picayune film critic Mike Scott shared that, the year prior, his editor had suggested he get started on an advance obituary for Simmons. It’s a common thing for a newspaper to do when a major figure is reaching a certain age—Simmons was then sixty-eight—but that wasn’t why the assignment had been moved up the priority list. “I’m worried about him,” Scott’s editor had told him.

Richard Simmons’s fame merited a news obit, of course, and he rated an original one in the Times-Picayune (as opposed to a piece from a wire service) because, though he’d spent most of his adult life in L.A., he was still a hometown boy. Born Milton Teagle Simmons in New Orleans in 1948, as a teenager he sold pralines at a Royal Street shop and gave tours of the Musee Conti Wax Museum and St. Louis Cathedral. He was the second generation of his family to work in the French Quarter: his parents, Shirley and Leonard, had both been entertainers there, though later his mother danced as a solo performer (“Both my parents were dancers once,” he told the Times-Picayune in a 1981 profile, “but when my mother started working alone, she wasn’t successful because she wouldn’t take off her clothes. And that didn’t go over on Bourbon Street.”) and his father became a costumer, sewing glittering beaded gowns for her shows until she retired from the stage and went to work at Maison Blanche. His older brother, Leonard Jr., bucked the family performance tradition and worked at New Orleans City Hall for decades, eventually serving as the city’s chief administrative officer.

By 1981, the Los Angeles–filmed The Richard Simmons Show, which combined chat, exercise, and the host’s special pep-talk cheerleading, was syndicated in close to eighty markets, including Lafayette, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. And Richard Simmons was a long way—at least outwardly— from being the kid who’d been mercilessly bullied, he often said in interviews, at St. Louis Cathedral School and Cor Jesu (now Brother Martin) High School. Unhappy with his size, which had been his antagonists’ favorite weapon, he’d dropped more than a hundred pounds on crash diets as a young man, starving himself to the point that he lost his hair, which he later replaced painfully with surgically implanted plugs. But he’d later found a healthier diet and exercise system that worked for him, and after a period of small-part acting and trying to shop television scripts, he’d thrown himself into the performance persona that fit him best—himself.

In the world of fitness personalities at the end of the twentieth century, Simmons was unique. He wasn’t a strongman like Jack LaLanne or a stern mistress like Jane “Feel the Burn” Fonda, and he was certainly no borderline abuser in the mold of later stars like Susan Powter (who once called Simmons “the Liberace of wellness”) or The Biggest Loser’s Jillian Michaels. He welcomed older people, larger people, and blatantly uncool people—weight-loss hopefuls from anywhere, mostly women, who warmed to the accepting, compassionate modus operandi he employed long before the mainstreaming of body positivity. That’s not to say Simmons was pro-fat. He chided his acolytes toward a supreme goal of thinness, but with the kind of “hate the sin but love the sinner” attitude you might expect from someone deeply steeped in Catholicism, which indeed he was. Though his mother was Jewish and his father Protestant, he’d been raised Catholic in the most Catholic of American cities, and at one point, he told the press in more than one profile, he’d considered entering the priesthood.

Maybe it was just nice to see that face again… beaming out to reassure us from a past when all we were anxious about was whether we could drop the pounds.

Instead, he decided to minister to those who struggled with their weight. (He did this, too, of course, in a way that telegraphed his New Orleans roots—not through his spiritual tone, but with his signature gem-spangled, flamboyant workout clothes.) And he did this with a remarkable selflessness and level of personal accessibility, spending hours on personal phone calls and later, emails, with fans, often praying with them in the halls and the wings of his public appearances. The overtones of religion in his style of coaching haven’t been lost on his chroniclers. A 2017 BuzzFeed piece on his sudden seclusion invokes Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrows and Mother Teresa in reference to his avid “ministering” to the unhappily overweight multiple times. A piece in the Jesuit magazine America compares Dan Taberski, the Missing Richard Simmons podcaster, to one of Christ’s disciples, more distraught at being abandoned than joyous for his teacher’s ascension.

The New York Times wasn’t the only outlet to scrutinize the fundamental moral issues raised by Taberski’s aggressive quest. The Atlantic referred to it as an “ethical minefield,” and Vulture wrote that it posed an “ethical quandary” about celebrity, privacy, and just exactly what is anybody else’s business.

There was ultimately not very much proof of Simmons’s sanity or relative safety between his retreat and today, considering how visible he’d been for most of his life. He’d only supplied a quick Facebook video and a call to the Today show. There was a report from the LAPD after a wellness check, saying he was not under threat, and, of course, the revival of his YouTube channel. In 2017, he was briefly hospitalized for what he told People in a statement was a gastrointestinal problem, and in 2020, he sued another celebrity magazine for hiring a private investigator who placed a tracking device on his car—apparent fallout from the podcast’s very widely heard concern for his safety. But there also wasn’t much to point to a nefarious explanation for his absence, either. In 2017 his brother, who still lives in New Orleans, told People that he had recently spent a few days with Richard, and that he was doing fine. So did his longtime manager. Do any of us, no matter how well-meaning, actually deserve an explanation from the star?

It’s reasonable to wonder why such a public person would make such a total about-face. Maybe there are clues to be found in the past: reading old Times-Picayune interviews with the then nascent star, for example, I found a 1981 piece in which he told the paper he was excited about a forthcoming episode on agoraphobia—not a hot topic at the time. And there’s also a tossed-off line in that 2013 New York Times profile. Listing his many attributes, the writer calls him a “piñata for late-night talk shows.” Simmons had spent almost forty years putting himself in the line of laughter, gamely making his shrill, outsized, and gay-coded persona the butt of jokes during regular appearances with David Letterman, Howard Stern, fellow New Orleanian Ellen DeGeneres, and other talk-show hosts. Had the once-bullied kid simply hit a wall?

The return of the YouTube channel might be a sign that Simmons is dipping an aerobicized toe into the possibility of a return to public life—but then again, it may be as much of himself as he’s able to give these days. For all we’ve received up until now, though—the sweat, the glitter, the encouragement—we ought to be thankful.

A columnist since 2016, Alison Fensterstock has written for 64 Parishes about music, dogs, witches, hippies, and other things.