Marie Baude

Baude was a free African woman who traveled from Senegambia to Louisiana in the eighteenth century.

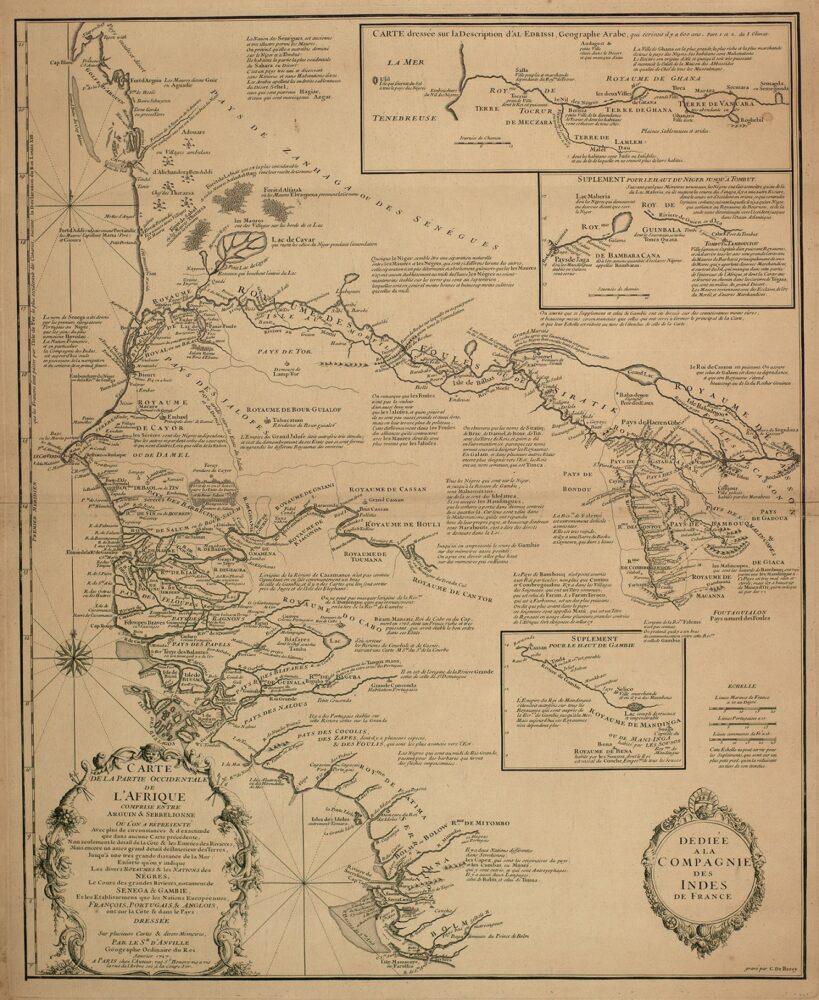

Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, The Historic New Orleans Collection

Carte de la partie occidentale de l’Afrique [Map of the western part of Africa]

Free African Women in the Atlantic World

Born free in Senegambia during the era of the slave trade, Marie Baude traveled from Saint-Louis-du-Sénégal to New Orleans as a free African woman in the 1700s.

In an era when the majority of Africans crossing the Atlantic Ocean traveled as captives aboard slave ships, Baude traveled as a passenger with enslaved property of her own. She was part of a tiny cohort of free African women who crossed the Atlantic at the time. Women like the Senegambian merchant Anne Rossignol, the Gambian trader Penda Lawrence, and the wealthy Sierra Leonian Elizabeth Cleveland Harcastle engaged in trade, including trade in enslaved Africans. They were part of multiracial, multiethnic networks that were formed by marrying or becoming the consorts of white European men. They were also vulnerable to the many dispossessions and violence that accompanied the rise of the slave trade and slavery in Africa and the Americas. Baude is one of the earliest known examples of these women, a reminder of the limits of freedom in a world of slaves.

A Daughter of Joal

Documentation on Baude’s life is scarce and fragmented, spread across multiple archives and three continents. According to Baude’s own testimony, she was born in 1701, almost fifty years after the French established a colonial presence on the coast of present-day Senegal. In 1659 the French fought the Dutch for control of the island of N’Dar at the mouth of the Senegal River. French traders established a comptoir, or administrative trading outpost, at N’Dar, renaming it Saint-Louis-du-Sénégal. In 1677 they did the same at the island of Ber, further south and off the tip of the Cap Vert peninsula, renaming the island Gorée. Baude, however, described herself as born at Joal, an escale, or trading outpost, just south of modern-day Dakar. As a daughter of Joal, Baude would have been born into a world of overlapping African polities. Joal existed within the territorial reach of the Wolof states of Kajoor, Waalo, and Bawol but under the administration of the Burr Siin, a kingdom that was predominantly Sereer. The region also had a long history of contact with Portuguese, Dutch, and British traders who preceded the French.

For African women in the region, navigating these complex dynamics would have required savviness, creativity, and care. The Wolof had a history of women heads of households and political figureheads, including lingeers, or female heads of state, as well as female aristocrats. However, the early eighteenth-century West African coast was largely patriarchal and male-dominated, with enslavement and sexual violence remaining a constant reality and threat. One of the ways women could secure some security and power for themselves was to form mariages à la mode du pays, or marriages with Europeans visiting the coast “in the manner of the country.” Through mariage à la mode du pays, in exchange for providing Europeans access to coastal and countryside trade networks, interpreter services, and hospitality, African women could secure access to European goods, trade networks, and the political power of being recognized as a wife without having to submit to Catholic marriage sacraments. Baude herself may have been the child of one of these marriages. Although her mother remains unknown, her father was a Frenchman, described in records as “Sieur Baude,” a French man. In 1721 Baude married a French gunsmith named Jean Pinet, either à la mode du pays or with Catholic sacraments. In celebration of the wedding, her father gifted the chaplain with a fourteen-year-old, enslaved boy named Gabriel Manuel.

La Femme Pinet Arrives in Louisiana

Three years after marrying, Baude stood before the directors of the Company of the Indies (Compagnie des Indes) at Saint-Louis, testifying about her husband. According to the testimony of witnesses, during an evening gathering at the Pinet home, Jean Pinet and an Afro-European sailor named Pierre LeGrain began to feud. When Pierre made a sexually explicit remark about Baude, Pinet defended his wife’s honor by taking up a sword and killing LeGrain. The murder investigation led Pinet to be deported to Nantes, France, where he was imprisoned. This event demonstrates the racial violence and misogyny that permeated even the African coast at this time as men fought each other for control. In the end, her husband’s act of violence would chart Baude’s path to Louisiana.

In 1726 Pinet was deported once again, this time from Nantes to colonial Louisiana to serve as a gunsmith for the Company of the Indies at New Orleans. In 1728 Baude boarded the slave ship La Galathée as a passenger, accompanied by three of her own slaves, and took the journey to meet her husband. La Galathée’s voyage was one of the more harrowing of the twenty-three slave ships that traveled from the African continent to Gulf Coast Louisiana during the French colonial period. At one point in the journey, the ship was forced to stop at Les Cayes, on the south coast of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), on the island of Hispaniola, to allow the captives and crew to recover from sickness. By the time it reached the Gulf Coast, 82 of the four hundred enslaved men, women, and children and 11 crew members had died. When the ship finally arrived in Louisiana, Baude survived but her enslaved property was confiscated in New Orleans by company officials who found her in violation of not paying import duties. (The Company of the Indies held a monopoly on the slave trade to Louisiana at this time.). Although in Senegambia, she may have been an African woman with property, community connections, and status, in Louisiana she kept neither her slaves nor her name—in the records she is simply listed as la femme Pinet, or the wife of (Jean) Pinet.

Pinet appealed to the Superior Council (Louisiana’s judicial body) to recover his wife’s enslaved property, but the slaves were sold alongside the others brought from Africa by the Company of the Indies. What became of Baude in the years following her arrival in Louisiana is unclear. She left few traces in the archival record, though the 1731 census showed her living with her husband, five African or African-descended people (likely enslaved), and one white servant in a house downriver from New Orleans. Baude’s journey and the complicated changes her life underwent despite her free status, property, and marriage, offers an illustrative tale. Baude may have been a free African woman with status on the African continent, but even she remained vulnerable to the gendered racial hierarchy that the Atlantic world created—the same world that shaped slavery in Louisiana.