The Hatchet Heroine

Carrie Nation invades New Orleans

Published: May 31, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

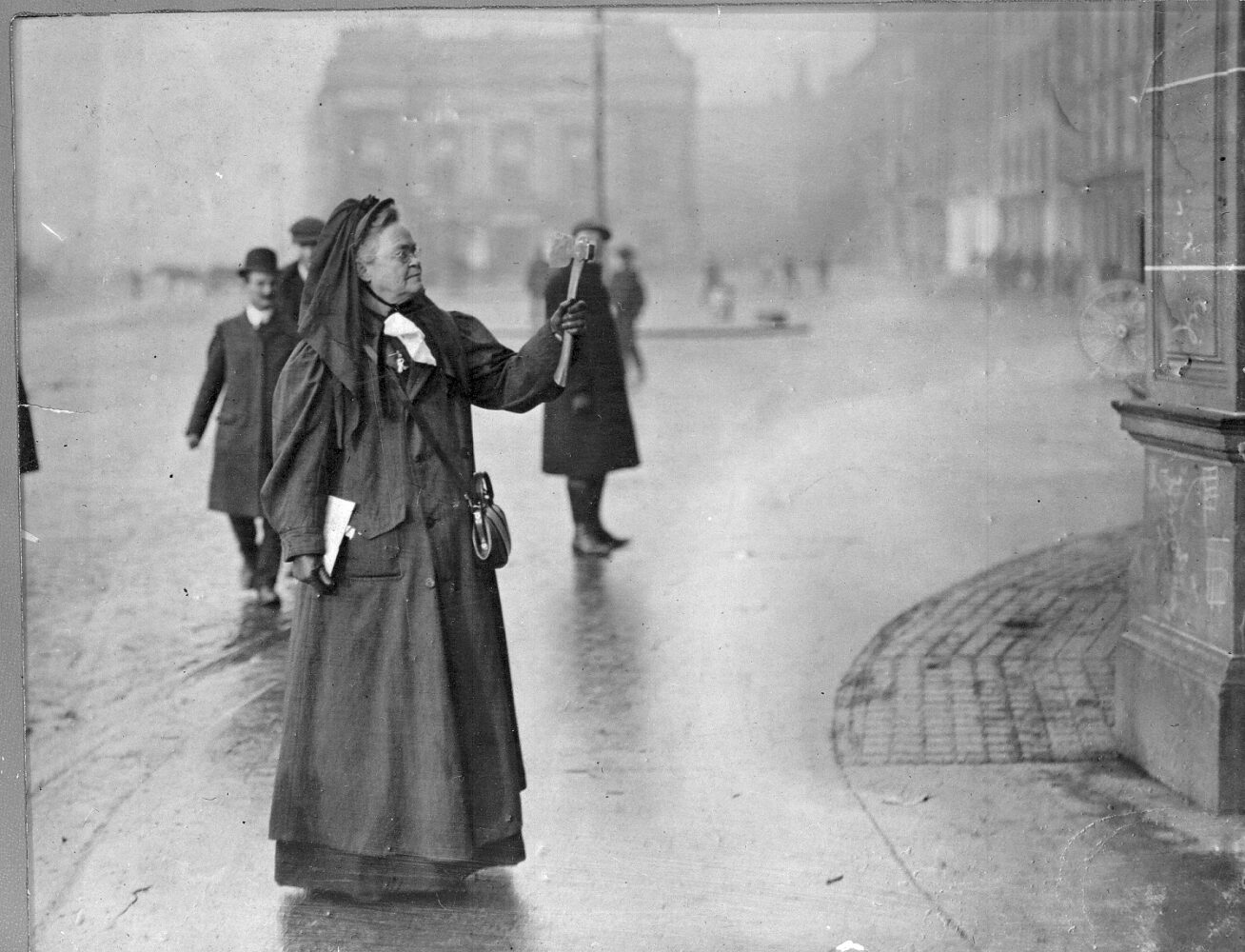

Kansas State Historical Society

A 1909 London News Agency image of Nation brandishing her trademark hatchet.

New Orleans was well-acquainted with reformers who had toiled mightily to effect change. None, however, reached the epic notoriety of the “Kansas smasher,” whose audacity, grit, and determination to liquidate any saloon in her path mesmerized the public. In an orgy of demolition, she assaulted dispensers of drink in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, California, and Pennsylvania, leading to brief jail terms in each for criminal damage. But as she believed that she was being martyred for righteousness, Nation coveted the attention those arrests gave her, proudly listing in her autobiography where and for how long she had been incarcerated. Some certainly ridiculed her as a dauntless buffoon, but others, women especially, viewed her with deep admiration. One did not have to be a prohibitionist to recognize the courage she demonstrated as she plowed her way through swinging screen doors and into the sacred sanctums of men. Reform organizations and church groups both in the United States and in the United Kingdom booked her for speaking engagements.

So it was that when Mrs. Nation’s train rolled into New Orleans just before Christmas, 1907, her visit created more excitement than the holiday season itself. She originally planned on skipping the city in her tour through the South, commenting to the Birmingham Age-Herald that New Orleans is “too tough a place for me to tackle. It is a very, very bad place.” Nevertheless, a week later she announced that she was coming. City Hall immediately sent word to the press that the Sunday Law closing all liquor emporiums on that day would be strictly enforced. It was like cleaning your bedroom before Mother came upstairs. There was hardly anywhere in America where she was more controversial, and the notion of her intruding into the Storyville district held great expectations for lusty fireworks.

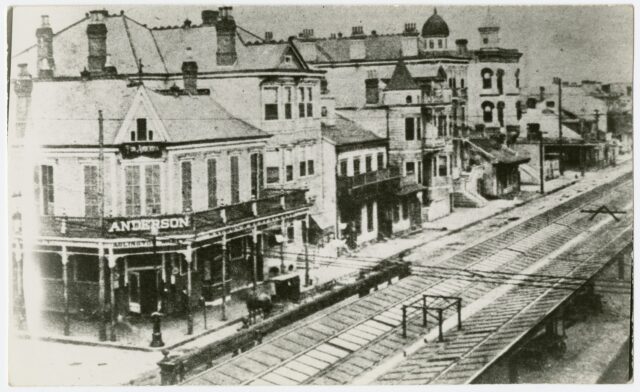

A view of the 200 block of North Basin Street in Storyville, ca. 1900. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Nation was the last person to step off the train, and she was immediately met by a scrum of reporters and spectators. It was the reception you might expect for Mary Pickford—but there was no resemblance whatsoever between her and the petite movie star with that cute smile and blonde curls. The avatar of temperance looked older than her sixty-two years, her black widow’s bonnet exposing a flurry of gray hair above her square face. A somber funereal cassock layered under a topcoat protected her imposing, nearly six-foot frame from the chill and rain. Nation’s thick spectacles did not fool one reporter, who knew of her keen eye for acts of immorality, as well as her unerring sense of smell for whiskey or tobacco on the breath of a passerby. This rare gift, he supposed, developed from her “sensitive nostrils dilating like a warhorse on the bugle call.” To their delight, she appeased the onlookers with a few anecdotes and bragged that she had been arrested thirty-two times during her violent confrontations with liquor purveyors. “This long, blue scar on my forehead,” she announced to a Daily Picayune reporter, “and the visible effects of a partial straightening of a broken wrist are life-long testimonies of my hand-to-hand contests with the devil.” Before leaving the station, she decorated the newsmen with tiny reminders of temperance—miniature gold-plated hatchet pins for their lapels—and distributed the latest edition of her own newspaper, The Smasher’s Mail. Then it was off to the Grunewald. But when she learned that its café served “demon rum,” she insisted on being led to a more modest hotel without this inconvenience.

Once settled, she called on Martin Behrman at City Hall. According to the Picayune, the mayor greeted her with polished cordiality, but quickly warned her that he would not tolerate any damage to private property. Nation assured him that she was disarmed, with no hatchet, and would not look to destroy any taverns “unless the Lord called upon her.” But would the mayor refuse the Lord’s right to smash? No, he replied, but he would prevent her from doing so, admonishing his guest for her misunderstanding of “divine instructions.” Stick to speechmaking, he advised, instead of “hatchetation.” (The word was fabricated by Nation herself.) Behrman escorted her to the door politely, but it was a stilted meeting at best. The country’s premier incendiary believed that most all of its political leaders were in bed with Satan, as they refused to pass legislation supporting a strict moral code of decency. And Behrman, particularly, was an accomplice.

Later that day, the Picayune reported, Carrie Nation delivered her first talk at the YMCA auditorium on St. Charles Avenue. Her tirade against the evils of alcohol, gambling, tobacco, and other stimulants, sprinkled mightily with Bible verses, was a reprise of previous speeches. Then the unexpected. The silver-haired crusader turned her venom against a ladies’ undergarment. She labeled the “corset curse” as one of the greatest iniquities of the day, for it “unfit thousands for the ordeal of motherhood.” The devices, she claimed, “gird women’s loins with weakness.” The steel and whalebone girdles “jam their stomach, heart, and liver together and render some of the most delicate organs weak and unable to perform their offices.” The result, she argued, is that women are left entirely ill-equipped for marriage.

Nation saved perhaps her strongest rebuke for President Roosevelt and the other “beer-guzzling Dutch” for marketing their favorite drink. Our government, she ranted angrily, “has an agreement with hell” and had become a “refuge of lies.”

Women’s suffrage was on her agenda as well, parroting the New Orleans Gordon sisters, Kate and Jean, and their fellow suffragists. “Why is it that men—saloon men, ignorant foreigners, and Negroes—can vote to license the traffic which destroys our homes,” she asked the crowd indignantly, “and the American mother must stand by helplessly, not being entrusted with the privilege of the ballot?” But Nation saved perhaps her strongest rebuke for President Theodore Roosevelt and the other “beer-guzzling Dutch” for marketing their favorite drink. Our government, she ranted angrily, “has an agreement with hell” and had become a “refuge of lies.” She considered Roosevelt’s daughter, Alice, quite a disgrace in her own right, betting on horseraces while she puffed away at cigarettes and hit the bottle hard—she “got so drunk on one occasion that she puked all over an automobile.”

This last statement was way too graphic for the genteel readers of the Picayune. The newspaper apologized the very next day for its misjudgment in allowing such a remark to be printed. Even though Louisiana was a solidly Democratic state and awarded Roosevelt with less than 10 percent of its vote in 1904, the Picayune readers did not approve of attacks on the president’s daughter. The editor’s apology revealed the ambivalence experienced by many New Orleanians. They yearned for a cleaner city with a more progressive reputation, but they demonstrated little tolerance for outsiders and radical agitators. The newspaper blasted Nation for indulging in some “disgusting remarks” about a highly regarded lady. The reference was “shameful” to respectable people. Moreover, it took offense at the provocateur’s pious attacks on the sale of alcohol which was, it reminded, legal and “entirely proper.” They were “outbursts of an irresponsible person and carry no weight with them.” If change was coming, most wanted it at a pace they would decide for themselves.

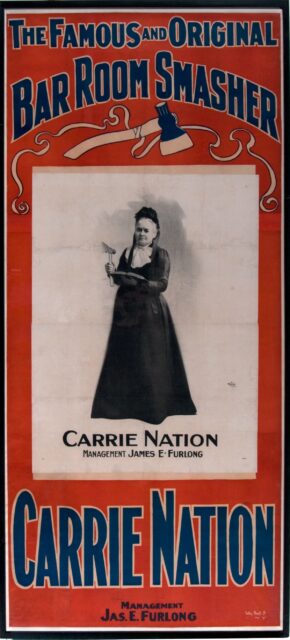

New York theater manager James Furlong bailed Nation out of a Topeka jail in July 1901 in exchange for a series of appearances at his theater, which were promoted by this banner. Kansas State Historical Society.

Hardly dismayed by the Picayune retort, Nation, uninvited, crashed a benefit dance at the Washington Artillery Hall to investigate what “devil business” was taking place there. When word got out that the Hatchet Hellion was in their midst, the attendants huddled around her to get a glimpse. Most stared. Others laughed. Then someone beckoned her to speak. She could not resist such an opportunity. Mounting a chair in the center of the dance floor with some help, she urged the boys there to never marry a girl who smoked or allowed them to “hug” while dancing—sure signs of promiscuity. That elicited a round of hooting and jeering. “Hey Carrie,” yelled a twenty-something on the floor, “aren’t you going to give me the next waltz?”

“Now look here,” she retorted calmly. “Fall in love with girls. That’s alright; but no man who loves a girl is going to take her out and hug her in public.” It appeared that she won few converts in the exchange. On her way out, another one of the unconvinced called out to Nation to share a beer with him. She smiled, so immune was she to ridicule and abuse.

Nation then asked to be driven to police headquarters to speak to the chief, where she was told by those in the office that he was unavailable. An accompanying reporter noted that she spotted one detective smoking at his desk, marched across the room, and firmly ordered him to throw the cigarette away, which he quickly did. (He was spared embarrassment. Her usual instinct was to grab a lit cigarette or cigar right from the mouths of smokers and dispatch it with disdain under her boot). She offered them her dissertation on the evils of dance halls, Satan’s fluids, women’s tights, and tobacco. On her way out of the building, she pinned one of her gold hatchets on the elevator boy’s jacket.

She visited the Orpheum Theater and demanded to see the manager. If he didn’t come out, she threatened to come in. When that message reached his office, he reluctantly crept into the lobby to confront the Kansas fury. After learning a little about the performances, Nation berated him for allowing a stage show where one woman impersonated a drunken man. Neither was the Bible-toter pleased when another actress pulled up her skirt a few inches and made reference to her skinny legs during the punchline of a joke. How could he allow a maiden to expose her limbs to a pack of groveling men? Waving her finger in his face like a whip, she asked the manager, “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?” He provided no answer.

Off to the Fair Grounds race track she went with her bodyguard and a troop of newspaper men in tow. The wagering that took place there was thought to be one of those ignitions certain to detonate the Kansas powder keg and create a satisfactory amount of bedlam for the reporters’ benefit. They hoped. Sam Gilbert, then a cub reporter for the Picayune, remembered years later that a horse named “Gee Whiz” elicited a rebuke from the crusader because she hated profanity. According to Gilbert in Dixie magazine of October 19, 1958, she strode right into the betting ring, the “den of wickedness” as she called it, just before the fourth race. Railbirds and clubhouse bettors both gazed at the “grim, Amazon-like smasher as though . . . she was some sort of spirit of evil.”

Then in the lull between races, she stood near her seat and belted out a tame admonishment, one that would have been better suited for a children’s Sunday school classroom: “We’re running a much more important race, and if we’re good we’re going to be winners and given a home in heaven. That is the race of life!” She reminded them that trust in Jesus was what they needed. Before leaving, she sold more of her tiny hatchets and copies of her newspaper to a few admirers and souvenir hunters. Then she disappeared.

Perhaps she was tiring. Perhaps her old vocal cords no longer produced like they once did. “Carrie Nation Disappoints” read the following day’s Item headline.

Proselytizing in Storyville, the city’s notorious red-light district, would test the Kansan’s nerve. This was virgin territory for her, so to speak, and perhaps was why she initially balked at coming to New Orleans. At around ten o’clock in the evening on December 21, she began a short tour of the district—with a police escort. One wondered which they were protecting—her or the brothels.

Emma Johnson, proprietor of the most deviant establishment in Storyville, had actually invited Nation to her House of All Nations, calling for all her unencumbered girls to meet their guest. With her trademark bluntness, Nation questioned their decision to enter their trade. The women assured her that they were not unhappy with their lives. Johnson explained to her visitor that she too was a prayerful woman who hoped to reach heaven.

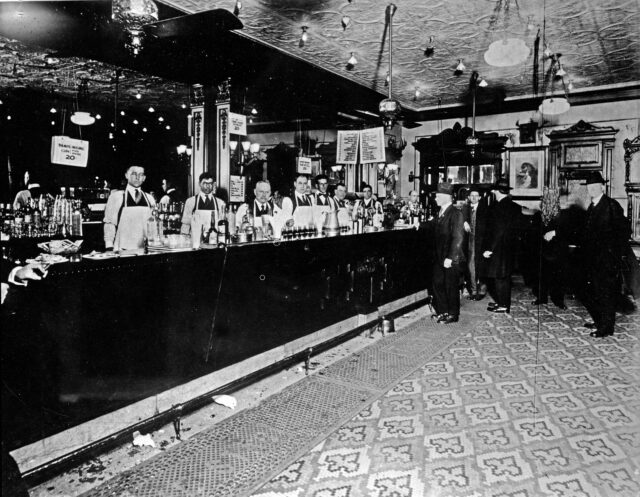

Interior of the Star Saloon in New Orleans, ca. 1915. Photo by Charles L. Franck, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

The famous rogue’s next stop was the Arlington and its hot-tempered and surly madam, Josie Arlington, who once bit off half of another woman’s ear in a fight. Inside the Basin Street brothel, Nation, after a short homily, dropped to her knees on the polished floor to pray for the wayward women there. All present maintained a good measure of courtesy. But it was clear that none paid much attention to her admonitions. Instead they guided her to the dance floor to watch a few of the girls perform “the glide” to the sounds of a lively pianist. Before Nation left, Arlington pledged to start a home for fallen women once she retired and “got a little richer.”

The last stop was Tom Anderson’s place. According to Sam Gilbert, Anderson—the “mayor” of Storyville—was ready for her. He hid his high-end inebriants and had a regular customer stand nearby with a smoke. This time she was not able to resist the bait. Nation yanked the cigarette from the fall guy’s mouth and crushed a few whiskey glasses laid out for her on the bar. Then the smasher turned to Anderson for his reaction. He reportedly bowed to her and said, “Mrs. Nation, the pleasure is all mine.” Someone provided Nation with a glass of milk, as well as a crate for her to use as a platform for her harangue against the usual culprits of sin. But her sermon was cut short. As midnight Saturday approached, the police interrupted her and led everyone out in observance of the Sunday closing law that put a cork in liquor bottles all around town.

Outside, the street was thick with celebrity watchers and hecklers yelling for a street speech. But the exhausted reformer only waved, smiled, piled into her escort’s vehicle, and slipped away.

When Carrie Nation brought her souvenir hatchets to pass out to New Orleanians, she was received as a comic-strip character, a misplaced oddity, a source of free entertainment. A decade later, however, the message of her homilies—and the bare-knuckle methods of the Anti-Saloon League, one of the most effective pressure groups in US history—were finally taking hold. By 1916, twenty-three states had passed laws limiting alcohol sales. The temperance movement of the nineteenth century had finally come to fruition. Prohibition was set to become law in January of 1920.

Author and historian Brian Altobello is a native of New Orleans with undergraduate and graduate degrees in US history from LSU. His most recent book, Whiskey, Women, and War: How the Great War Shaped Jim Crow New Orleans, was published by the University Press of Mississippi. Retired from teaching, Brian is now employed as an onboard historian sailing the Mississippi River to Memphis on the American Queen paddle wheeler.